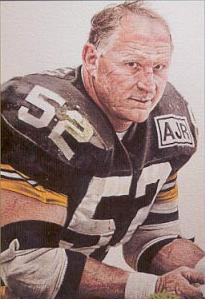

Sports Illustrated made the following statement about football not in 2015 but in 1978: “The game is headed toward a crisis, one that is epitomized by the helmet, which is both a barbarous weapon and inadequate protection.” This dire warning was attached to a series of articles reported by John Underwood about the dark side of Monday Night Lights, a clarion call about the devastating injuries that are endemic to the game, among other unsavory elements of the gridiron.

Since then, the sport hasn’t faced endgame, anything but, as football replaced baseball as America’s pastime, with its ubiquitous fantasy leagues and gambling and sophisticated content-delivery system. But that doesn’t mean Underwood wasn’t prophet, as the commonplace concussions–which just led Chris Borland to retire from the NFL at 24–aren’t going anywhere, no matter what type of helmet is developed. You can’t stop that type of whiplash, the brain slashing around inside the skull. The NFL’s ruling class is awfully good at self-delusion, but they worry sooner or later parents will steer youngsters from football the way they now do from boxing, the former king of sports.

From Underwood:

Once there was a game that had practically everything. Fun to play and exciting to watch, it was beloved by a nation of sports-minded people. It was held up to the nation’s youth as an exemplary physical test and as a builder of character. Outstanding men, including Presidents and Supreme Court Justices, had played it in their youth. Many observers considered it to be the definitive American game.

In time, the sport developed a professional adjunct. It was shown on television and was used to sell automobiles, beer and “pieces of the Rock.” As a result, some of the men who played the game were idolized and became rich.

Statistics showed that it was the nation’s most injurious team sport, but those who despaired of the weekend casualty lists were encouraged to look at the sport’s virtues, at the lives and profit statements it enhanced.

The game became contaminated, but the process was so gradual and insidious that few took notice. From the kiddie leagues to the major colleges and professional league, the sport’s public image grew more robust even as it decayed within. The injury rate mounted, sportsmanship declined. Vicious acts became commonplace.

Reform, though obviously needed, was resisted by the sport’s custodians. Most of its coaches were too busy trying to stay employed. They were also reluctant to give up “proven” coaching tenets. They said injuries were “part of the game.” They were supported in this by the players, who were busy trying to keep their scholarships or make their fortunes. For their part, the sport’s administrators were too busy trying to maximize their profits.

Eventually the professional league commissioned a study of injuries. The investigation was supposed to be private, but word of it got around. The study showed that the game’s equipment and many of its rules needed to be overhauled to keep pace with the times. Players were bigger, faster and stronger, but the laws of physics were constant: e.g., force=mass X acceleration. Nonetheless, the report was regarded as science fiction by the league. Only minimal changes were made; key recommendations were ignored.

Excess begot excess. Some of the sport’s paid stars were glorified for the “macho” way they broke the rules. A psychiatrist wrote firsthand about the amphetamine abuses of one pro team and how the drug contributed to injury. For this he was discredited by the league, which led a move to have his license revoked.

No sin was too great for absolution. College coaches caught cheating one year were named “Coach of the Year” the next. Pro players threatened officials, and each other, with impunity. The sport suddenly found itself crawling with lawyers. Charges ranging from breached contracts to slander were hurled. Players–teen-agers and adults–filed suit, seeking recompense for their broken bodies. Manufacturers of the game’s equipment learned they were faced with Judgment Day. The cost of insuring the game against itself soared alarmingly.

And all the while men of goodwill who loved the sport, and were involved in it, grew fearful for its future.

And wondered what would happen next.

And if any good seats were left for the big game.•