I’m sure reading moral philosopher Peter Singer’s classic book Practical Ethics played some role in my giving up eating and wearing animals. In a new Reddit AMA, which is tied to the publication of his latest title, The Most Good You Can Do, Singer assesses the correct responses to various ethical challenges. A few exchanges below.

_________________________

Question:

What are your thoughts on a universal basic income?

Peter Singer:

Nice idea, but it would need to be truly universal, i.e. I’d like to see everyone in the world have a guaranteed minimum that would mean that no one was unable to buy enough food to live. Unfortunately, I can’t see this being implemented in the near future, so in The Most Good You Can Do I focus on action that is cost-effective and practical right now.

_________________________

Question:

Do you think that it’s wrong to buy lamb and beef that has come from sheep and cattle that have lived non-factory farmed lives outdoors in fields? It’s seems to me that the lives of such animals are worth living, i.e. that the world is better off for containing such animals than not, and therefore (from an animal welfare perspective at least) it is good and right to buy lamb and beef from these sources; this would not preclude simultaneously compaigning for improved treatment of these animals. Do you agree?

Peter Singer:

The lives of sheep and cows kept on grass rather than in feedlots may be worth living, but unfortunately these ruminants produce a lot of methane (essentially, belching and farting) and so make a big contribution to climate change. Despite the myth of this being “natural” grass-fed beef and lamb, on the scale on which we are producing it, is simply not sustainable.

_________________________

Question:

In an interview you did with Tyler Cowen back when you wrote The Life You Can Save, you were asked what you think about immigration as an anti-poverty tool. At the time you said you need to think about it more. It seems to me that allowing more immigration may be the most effective political change we can make toward reducing poverty, so I’m curious if you’ve spent more time on that question since then and have an opinion on it?

Peter Singer:

Yes, I’ve thought about it some more, and looked at some of the arguments in favor of Open Borders. To me, though, the problem is that any political party that advocated this would lose the next election, and that election contest would probably bring out all the racist elements in society in a very nasty way. So until people in affluent nations are much more accepting of large-scale immigration than they are now, in any country that I am familiar with, I don’t think a large increase in immigrants from developing nations is feasible.

_________________________

Question:

I recently completed my PhD in philosophy, but throughout grad school, I have become completely disillusioned with academic philosophy (no jobs, prestige-obsessed, intimidating/arrogant people, etc.). But I love philosophy very dearly, and I’ve been told I stand a decent chance at getting a postdoc. If you weren’t doing what you do now, what do you think you’d be doing? And do you think you’d have any regrets?

Peter Singer:

I suppose I might be a political activist of some kind. Back in Australia in the ’90s, I was a political candidate for the Greens. I didn’t get elected, but support for the Greens has grown since then, and Green candidates have won the Senate seat for which I stood. I’m not sorry that I lost, because it was after that that I was offered the position at Princeton that has enabled me to have a lot more influence in discussions of the issues raised both in Animal Liberation and in The Most Good You Can Do but I often wonder what my life would have been like if I’d won. (Incidentally, Australia has proportional voting for the Senate, so it’s not the case that I could have helped the worse candidate get elected, as Ralph Nader’s candidacy did in the 2000 presidential election between Bush and Gore. I would not stand as a minor party candidate under those circumstances.)

_________________________

Question:

What would you consider to be the greatest danger to a more ethical future?

Peter Singer:

We tend to be ethical only when our survival, and that of those we care about, is not at stake. One of the big present dangers to our present level of security is climate change, which could create a chaotic world with hundreds of millions of people who are unable to feed themselves, and become climate refugees, causing a chaotic world.

_________________________

Question:

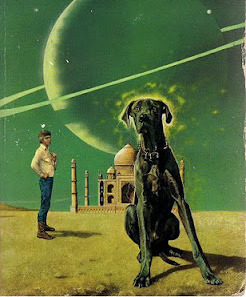

Would you rather save the life of 1 horse-size duck or 100 duck-size horses?

Peter Singer:

An effective altruist would always prefer to save 100 lives rather than just one.•