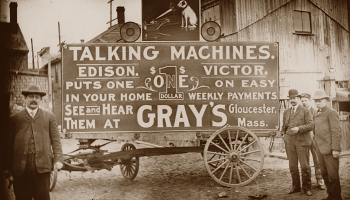

The phonograph was initially a disappointing technology commercially, even if Thomas Edison was something of a smash when he demonstrated his “talking machine” in London in 1888. One nineteenth-century Brooklyn undertaker, however, found a novel use for the new contraption during the funeral of young freak-show performer. An article in the August 18, 1895 Brooklyn Daily Eagle described the unconventional ceremony.

Tags: Augusta Burr, Undertaker Stillwell

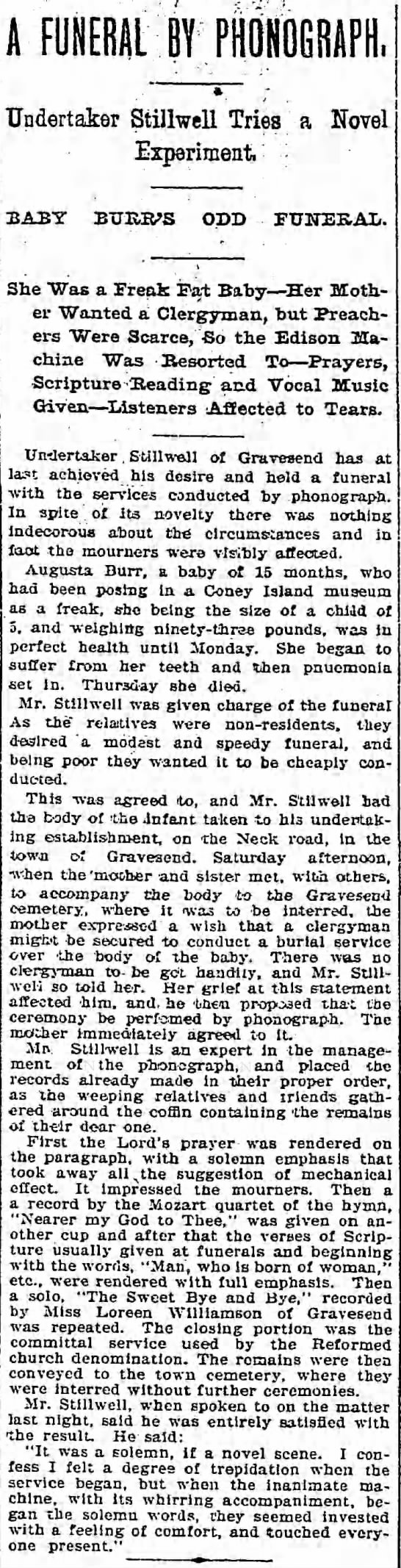

In 1973, the former child preacher Marjoe Gortner was hired by OUI, a middling vagina periodical of the Magazine Age, to write a deservedly mocking article about the American visit of another youthful religious performer, the 16-year-old Maharaj Ji, an adolescent Indian guru who promised to levitate the Houston Astrodome, a plot that never got off the ground. Two excerpts from the resulting report published the following May, which revealed a tech-friendly and futuristic cult leader, who would have been right at home in today’s Silicon Valley.

____________________________

The guru’s people do the same thing the Pentecostal Church does. They say you can believe in guru Maharaj Ji and that’s fantastic and good, but if you receive light and get it all within, if you become a real devotee-that is the ultimate. In the Pentecostal Church you can be saved from your sins and have Jesus Christ as your Saviour, but the ultimate is the baptism of the Holy Ghost. This is where you get four or five people around and they begin to talk and more or less chant in tongues until sooner or later the person wanting the baptismal experience so much-well, it’s like joining a country club: once you’re in, you’ll be like everyone – else in the club.

The people who’ve been chanting say, “Speak it out, speak it out,” and everything becomes so frenzied that the baptismalee will finally speak a few words in tongues himself, and the people around him say, “Oh, you’ve got it.” And the joy that comes over everybody’s faces! It’s incredible. It’s beautiful. They feel they have got the Holy Spirit like all their friends, and once they’ve got it, it’s forever. It’s quite an experience.

So essentially they’re the same thing pressing on your eyes while your ears are corked, and standing around the altar speaking in tongues. They’re both illuminating experiences. The guru’s path is interesting, though. Once you’ve seen the light and decided you want to join his movement, you give over everything you have–all material possessions. Sometimes you even give your job. Now, depending on what your job is, you may be told to leave it or to stay. If you stay, generally you turn your pay checks over to the Divine Light Mission, and they see that you are housed and clothed and fed. They have their U. S. headquarters in Denver. You don’t have to worry about anything. That’s their hook. They take care of it all. They have houses all over the country for which they supposedly paid cash on the line. First class. Some of them are quite plush. At least Maharaj Ji’s quarters are. Some of the followers live in those houses, too, but in the dormitory-type atmosphere with straw mats for beds. It’s a large operation. It seems to be a lot like the organization Father Divine had back in the Thirties. He did it with the black people at the Peace Mission in Philadelphia. He took care of his people-mostly domestics and other low-wage earners–and put them up in his own hotel with three meals a day.

The guru is much more technologically oriented, though. He spreads a lot of word and keeps tabs on who needs what through a very sophisticated Telex system that reaches out to all the communes or ashrams around the country. He can keep count of who needs how many T-shirts, pairs of socks–stuff like that. And his own people run this system; it’s free labor for the corporation.

____________________________

The morning of the third day I was feeling blessed and refreshed, and I was looking forward to the guru’s plans for the Divine City, which was soon going to be built somewhere in the U. S. I wanted to hear what that was all about.

It was unbelievable. The city was to consist of ‘modular units adaptable to any desired shape.’ The structures would have waste-recycling devices so that water could be drunk over and over. They even planned to have toothbrushes with handles you could squeeze to have the proper amount of paste pop up (the crowd was agog at this). There would be a computer in each communal house so that with just a touch of the hand you could check to see if a book you wanted was available, and if it was, it would be hand-messengered to you. A complete modern city of robots. I was thinking: whatever happened to mountains and waterfalls and streams and fresh air? This was going to be a technological, computerized nightmare! It repulsed me. Computer cards to buy essentials at a central storeroom! And no cheating, of course. If you flashed your card for an item you already had, the computer would reject it. The perfect turn-off. The spokesman for this city announced that the blueprints had already been drawn up and actual construction would be the next step. Controlled rain, light, and space. Bubble power! It was all beginning to be very frightening.•

____________________________

“The Houston Astrodome will physically separate itself from the planet which we call Earth and will fly.”

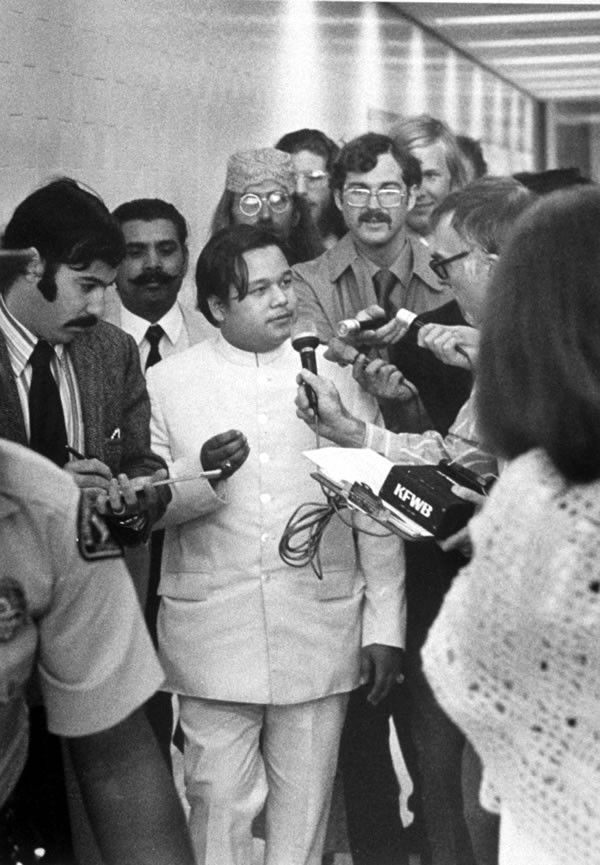

I think the best postscript I’ve read to the unfortunate auto crash that just claimed the lives of John and Alicia Nash is the Q&A Zachary A. Goldfarb of the Washington Post conducted with Sylvia Nasar, author of the wonderful book about the mathematician, A Beautiful Mind, which was masterfully adapted for the screen by Akiva Goldsman. In one exchange, Nasar reminds that even the relatively happy third act of Nash’s life was complicated. An excerpt:

Zachary A. Goldfarb:

How did he spend the last 21 years, since he won the Nobel?

Sylvia Nash:

The first time I saw him was a few months after he won the Nobel, and he was going to a game theory conference in Israel. He was surrounded by other mathematicians, and he looked like someone who had been mentally ill. His clothes were mismatched. His front teeth were rotted down to the gums. He didn’t make eye contact. But, over time, he got his teeth fixed. He started wearing nice clothes that Alicia could afford to buy him. He got used to being around people.

He and Alicia spent a lot of their time taking care of their son, Johnny, and doing the things that are so ordinary that the rest of us don’t think about them. Once I asked him what difference the Nobel Prize money made, and he literally said, “Well, now I can go into Starbucks and buy a $2 cup of coffee. I couldn’t do that when I was poor.” He got a driver’s license. He had lunch most days with other mathematicians, reintegrating into the one community that mattered to him most.

The last time I was with him was about a year ago when Alicia organized a really lovely dinner with us and two other couples. John was talking about all the invitations they’ve gotten and all the places they’ve planned to travel. Johnny was there. He was still very sick. They took him to a lot of the places they went and always tried to include him. Their life was a mix of glamour and celebrity – and the day-to-day which revolved around Johnny, who by then was in his 50s and was as sick as his father ever was and entirely dependent on them.•

Tags: Alicia Nash, John Nash, Sylvia Nasar, Zachary A. Goldfarb

In a Medium piece, Gerald Huff answers the points made by writer Walter Isaacson and roboticist Pippa Malmgren during a recent London debate, in which they argued against the likelihood of large-scale technological unemployment. Isaacson touting work created by the so-called Sharing Economy, contingent jobs which squeeze laborers, was either his least-researched response or most disingenuous one.

From Huff:

What is different about the technologies emerging now from academia and tech companies large and small is the extent to which they can substitute for or eliminate jobs that previously only humans could do. Over the course of thousands of years, human brawn was replaced by animal power, then wind and water power, then steam, internal combustion and electric motors. But the human brain and human hands — with their capabilities to perceive, move in and manipulate unstructured environments, process information, make decisions, and communicate with other people — had no substitute. The technologies emerging today — artificial intelligence fed by big data and the internet of things and robotics made practical by cheap sensors and massive processing power — change the equation. Many of the tasks that simply had to be done by humans will in the coming decades fall within the capabilities of these emerging technologies.

When Isaacson says “it always has, and I submit always will produce more jobs, because it produces…more things that we can make and buy” he is falling into the Labor Content Fallacy. Without repeating the entire argument in the linked article, there is no law of economics that says a product or service must require human labor. The simplest example is a digital download of a song or game, which has essentially zero marginal labor content. In the coming decades, for the first time in history, we will be able to “make and buy” a huge variety of goods and services without the need to employ people. The historical correlation between more human jobs due to increased demand for goods and services from a rising population will be broken.•

Tags: Gerald Huff, Pippa Malmgren, Walter Isaacson

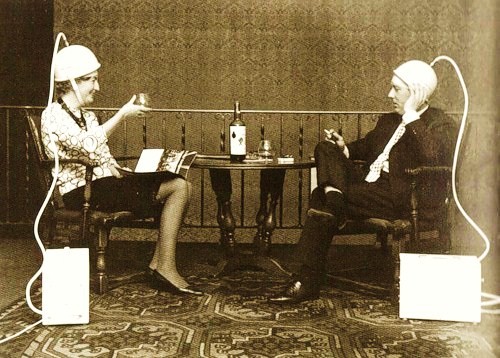

Even before the Internet, we’ve always been inside a hive mind of sorts, things have forever “gone viral” in one sense or another, though technology has made such functions more immediate, intricate and seamless. Of course, we’re only at the beginning. What becomes of us as individuals if our brains are always “plugged in” and we become a true neural collective, if our gray matter moves from “dial-up” to “broadband”? It will create new problems even as it helps solve many others.

A passage from “Hive Consciousness,” Peter Watts’ new Aeon essay:

Cory Doctorow’s novel Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom(2003) describes a near future in which everyone is wired into the internet, 24/7, via cortical link. It’s not far-fetched, given recent developments. And the idea of hooking a bunch of brains into a common network has a certain appeal. Split-brain patients outperform normal folks on visual-search and pattern-recognition tasks, for one thing: two minds are better than one, even when they’re in the same head, even when limited to dial-up speeds. So if the future consists of myriad minds in high-speed contact with each other, you might say: Yay, bring it on.

I’m not sure that’s the way it’s going to happen, though.

I don’t necessarily buy into the hokey old trope of an internet that ‘wakes up’. Then again, I don’t reject it out of hand, either. Google’s ‘DeepMind’, a general-purpose AI explicitly designed to mimic the brain, is a bit too close to SyNAPSE for comfort (and a lot more imminent: its first incarnations are already poised to enter the market). The bandwidth of your cell phone is already comparable to that of your corpus callosum, once noise and synaptic redundancy are taken into account. We’re still a few theoretical advances away from an honest-to-God mind meld – still waiting for the ultrasonic ‘Neural Dust’ interface proposed by Berkley’s Dongjin Seo, or for researchers at Rice University to perfect their carbon-nanotube electrodes – but the pipes are already fat enough to handle that load when it arrives.

And those advances may come easier than you’d expect. Brains do a lot of their own heavy lifting when it comes to plugging unfamiliar parts together. A blind rat, wired into a geomagnetic sensor via a simple pair of electrodes, can use magnetic fields to navigate a maze just as well as her sighted siblings. If a rat can teach herself to use a completely new sensory modality – something the species has never experienced throughout the course of its evolutionary history – is there any cause to believe our own brains will prove any less capable of integrating novel forms of input?

Not even skeptics necessarily deny the likelihood of ‘thought-stealing technology.’•

Tags: Peter Watts

In the IEET essay “Aristotle, Robot Slaves, and a New Economic System,” philosopher John G. Messerly uses Jaron Lanier’s Who Owns the Future? as a jumping-off point for a discussion of how we’ll live should we experience a critical mass of technological unemployment. Messerly is largely sanguine, predicting we’ll still enjoy life when we’re second best, the way we continue to play chess despite being checkmated by our silicon sisters. Of course, he doesn’t explain how we’ll get from here to there, how we will come to “share the wealth.” It may not be such a smooth transition.

An excerpt:

I think that Lanier is on to something. We can think of the non-automated work as anything from essential to frivolous. If we think of it as frivolous, then so too are the people that produce it. If we don’t care about human expression in art, literature, music, sport or philosophy, then why care about the people that produce it.

But even if machines write better music or poetry or blogs about the meaning of life, we could still value human generated effort. Even if machines did all of society’s work we could still share the wealth with people who wanted to think and write and play music. Perhaps people just enjoy these activities. No human being plays chess as well as the best supercomputers, but people still enjoy playing chess; I don’t play golf as good as Tiger Woods, but I still enjoy it.

I’ll go further. Suppose someone wants to sit on the beach, surf, ski, golf, smoke marijuana, watch TV, or collect coins. What do I care? Perhaps a society comprised of contented people doing what they wanted would be better than one informed by the Protestant work ethic. A society of stoned, TV watching, skiers, golfers and surfers would probably be a happier one than we live in now. (The evidence shows that the happiest countries are those with the strongest social safety nets, the ones with the most paid holidays and generous vacation and leave policies; the Western European and Scandinavian countries.) People would still write music and books, lift weights, volunteer, and visit their grandchildren. They would not turn into drug addicts!

This is what I envision.•

Tags: Jaron Lanier, John G. Messerly

help me find a shrinking potion (reno nv)

i’m looking for a real working way to shrink. i know its very strange, but i’m serious, and i know that there must really be a way. i would like to shrink myself to 3 inches tall. no joke. i’m a 24-year-old male. i’d do anything, anything to get a hold of something that really honestly works. thank you!

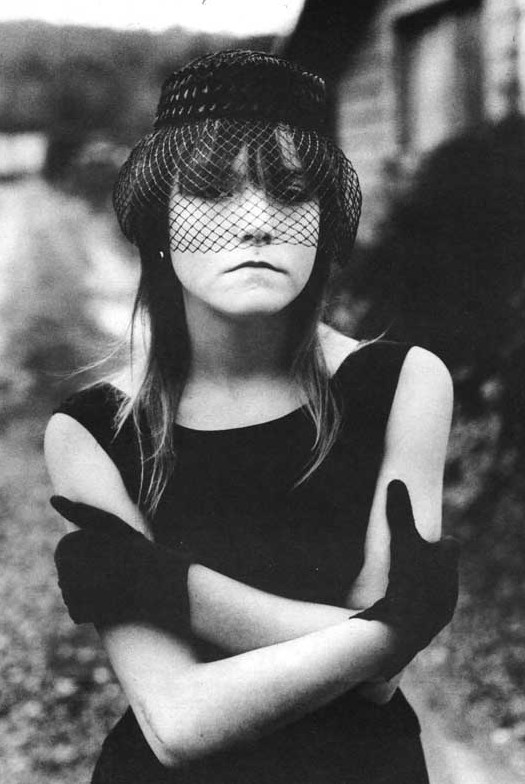

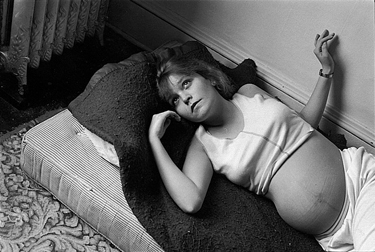

The photojournalist Mary Ellen Mark, best known for Streetwise, just passed away at 75. In 1987, Vicki Goldberg penned a longform NYT portrait of Mark, whose career ascended as documentary photography in print was being elbowed aside by pictures of celebrities with perfect teeth. Her sojourns inside brothels and hospices and gypsy camps and squats raised the old question about people who carry cameras into squalid corners–those of exploitation. These risky assignments improved Mark’s station in life, but how about her subjects? I feel certain we’re better for her work, even if a lone journalist, no matter how gifted and determined, can seldom counteract injustices we’ve unloosed upon the world.

An excerpt from Goldberg:

WHENEVER SHE PICKS UP A camera, Mark, 47, puts herself in an emotional no-man’s land. She claims that she doesn’t take risks–”War photographers do that”–yet hers is the archetypal saga of the photojournalist who conquers obstacles and emotional shock to bring back accounts of unexplored territory: hospices for the dying, brothels in India, camps for children with cancer.

She brings to all her photographs an unflinching yet compassionate eye. In the midst of exotica or on the fringes of society, where she often chooses to be, she does not exaggerate the unavoidably alien, freakish qualities a less complex photographer would emphasize, but tries to find clues to what is familiar and human. Thus a picture of three Indian prostitutes solemnly, uncomfortably awaiting a man’s decision becomes a poignant, harsher version of young girls at a dance. Mark says that Falkland Road, her 1981 book on the Bombay brothels ”was meant almost as a metaphor for entrapment, for how difficult it is to be a woman.”

Her subject matter raises an old question about photojournalism: Do photographers exploit those less fortunate than themselves for the sake of their art? Mark herself simply asks whether the poor should be ignored; many have eagerly posed for her, she says, precisely because they wished to be noticed at last. And as Richard B. Stolley, who as managing editor of Life magazine assigned to Mark many of her most important stories, puts it, ”If she weren’t such a good photographer, the charge would never arise.”

MARK ASSISTED HER HUSBAND, the film maker Martin Bell, on Streetwise, a documentary about homeless teen-agers she had photographed in Seattle. The film was nominated for an Academy Award. Her own honors include the University of Missouri’s top award for a feature picture story (twice), the Page One Award, the Leica Medal of Excellence, the Canon Photo Essayist Award, the Robert F. Kennedy Award (twice), the Philippe Halsman Award and numerous grants. She belongs on any list of top contemporary photojournalists with the likes of James Nachtwey, Sebastiao Salgado and David Burnett. Stolley refers to her as ”one of the top three or four in the world” and adds, ”she is probably the best – how can I put this without sounding sexist? – I don’t know of another woman photojournalist as good as she is now.”

Photojournalism has recently scaled new heights of public esteem. Museums and galleries lavishly display pictures that were previously seen only in print. Films like Under Fire and Salvador set the photojournalist on center stage and biographies of past masters assure that the legendary glamour shines on.

Yet at a time when magazines are cutting back on photo essays in favor of twinkling pictures of media stars and token illustrations in text pieces, outlets for photojournalism are steadily diminishing. Mary Ellen Mark is one of the few photographers today whose stories have regularly appeared in such publications as Life, The Sunday Times of London, The New York Times Magazine, Rolling Stone, Paris-Match, Stern and Time. And in a magazine forum that sometimes seems to be split between hardship and glitz, she has an offbeat and distinctive vision of both. She does essays on Ethiopian refugees or the elderly in Miami; then, to earn a living, she takes advertising and publicity stills for films and countless celebrity portraits.•

Tags: Mary Ellen Mark, Vicki Goldberg

Cultured meat isn’t happening today or tomorrow–even those with a vested interest don’t believe it will be commercially viable for at least two decades–but the cost of an in vitro burger has already fallen precipitously from its 2013 price of $325K (condiments included). When taste and price become reasonable, it will be a real market, and one that will destabilize the slaughterhouse and be far less damaging to the environment than the beef industry.

From Ariel Schwartz at Fact Company:

The artificial burger that you—or your science-fiction-loving friends—have been waiting for is real. And now it’s cheap, too.

It wasn’t long ago that test-tube hamburgers—meat made from small pieces of lab-grown animal muscle tissue—were just a glimmer in some mad scientist’s eye. Then, in 2013, the dream of an artificial burger suddenly got interesting. That’s when Mark Post, a researcher at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, announced that he had created a burger made from real meat grown in a lab (20,000 strips of muscle tissue, to be exact) for the unreasonable price of $325,000. Now that price has dropped to just over $11 for a burger ($80 per kilogram of meat), according to a recent ABC News interview with Post.•

Tags: Ariel Schwartz, Mark Post

I’ve barely read any science fiction in my life even though I read constantly. That’s a bad thing to admit, right?

In Ed Finn’s Slate interview with Neal Stephenson, tied to the publication of his latest novel, Seveneves, the author briefly comments on the existential threats we face. The exchange:

Question:

The story is a meditation on existential threats to the species. Having not so long ago founded Hieroglyph, a project dedicated to optimism, what do you think we should be most worried about and how do you see our chances?

Neal Stephenson:

Well, aside from the threat of a big asteroid impact, the thing that we should be worried about is climate change, which is going to happen. There’s no way to make it not happen now. I think that dwarfs everything else.

Question:

Do you see yourself as essentially an optimist in the long-range survival of the species?

Neal Stephenson:

Yes, I think that we’ve got the prerequisites that we need in the way of technical know-how and resources. There’s a lot of energy. There’s a lot of stuff for us to work with. Solving problems has become a kind of routine operation, and so now it’s really a matter of organizing people in some way that doesn’t have terrible side effects.•

Tags: Ed Finn, Neal Stephenson

“Militarized Space Race” doesn’t have a comforting ring to it, but Neil deGrasse Tyson (mischievously) asserts that’s what the U.S. and China need to engage in to kickstart in earnest a voyage to Mars. Perhaps.

I don’t know that the fear of China is the same as it was with Russia during the Cold War. I mean, we’re practically partners with China, and they’re good communists capitalists just like we are. Ultimately, I don’t know if it matters which nation gets there first. The whole world benefited from Apollo even if the bragging rights and flag-planting were awfully sweet. Would a competition between the two leading economies work better than the nations agreeing to work together to get to Mars ASAP? Perhaps the competition should be between government and private industry instead? Us vs. Musk?

From Chris Zappone of the Sydney Morning Herald:

In the search to find the high-paying jobs and industries of the future, Neil deGrasse Tyson has an idea for a novel solution. How about a militarised space race to Mars?

More specifically, the famed American astrophysicist says that if he could just get China’s leaders to leak a memo to the West about plans to build military bases on Mars, “the US would freak out and we’d all just build spacecraft and be there in 10 months.”

The fallout of such competition would, like the Space Race of yore, alter the technological focus of advanced economies, likely helping shake off the current period of low growth and innovation stagnation in favour of new industries for the future.“This would reignite the flames of innovation that I think we, at least in the US, at one time took for granted,” Tyson told Fairfax Media from New York. And while Tyson offers his plan for Mars with tongue firmly planted in cheek, the issue of growing an economy through more science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) is no joke. …

In fact, the dazzling feats of humans in space would change the broader culture of a country.

“You would transform a sleepy country into an innovation nation and you’d do it practically overnight. And that transformation has huge economic implications,” he says.•

Tags: Chris Zappone, Neil deGrasse Tyson

This has already been a remarkably rich year for new books, but the best one I’ve read so far is Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens. Dense with ideas and beautifully written, it’s a dazzling, wide-ranging look at how we came to be the only human species on Earth, and how that may very well change in the future. The Guardian has a cheeky piece succinctly explaining Harari’s feelings regarding cyborgism. An excerpt:

What did he say? “I think it is likely in the next 200 years or so homo sapiens will upgrade themselves into some idea of a divine being, either through biological manipulation or genetic engineering or by the creation of cyborgs, part-organic part non-organic.”

Aren’t historians supposed to talk about the past, mainly? Yes, and Harari does also do that. He reckons that great fictions such as religion and money have been the key to humanity’s success because they made people function in large, flexible communities.

I see. Can I have his royalty cheques, then? I suggest you ask him about that. He also thinks these fictions are now reaching their limits because technology will make rich people amortal and virtually all-powerful, meaning that they won’t need God any more.

What’s amortal? It means, theoretically, you could live for ever, as long as someone doesn’t get annoyed and smash you up.

Far from guaranteed, I should think. And how will technology accomplish this? Well, you could have intelligent nanobots injected into your blood to rejuvenate your cells and repair any damage. You could implant a computer and various utensils into your body, giving you superhuman powers. Or you could just simply upload your mind into a computer so you could exist anywhere and experience anything.•

Tags: Yuval Harari Noah

Robert Bigelow wants to be a realtor to the stars–literal stars.

The Space Act just passed by Congress makes it legal (in this country, at least) for U.S. companies to keep anything they mine from asteroids, other planets, etc. The entrepreneur Bigelow wants the government to go further and give him permission to develop inflatable real estate on a patch of the moon.

From Brian Fung at the Washington Post:

Under the SPACE Act, which just passed the House, businesses that do asteroid mining will be able to keep whatever they dig up:

Any asteroid resources obtained in outer space are the property of the entity that obtained such resources, which shall be entitled to all property rights thereto, consistent with applicable provisions of Federal law.

This is how we know commercial space exploration is serious. The opportunity here is so vast that businesses are demanding federal protections for huge, floating objects they haven’t even surveyed yet. …

Technically the FAA’s jurisdiction covers launches and reentries only — but under a request from hotel and aspiring aerospace mogul Robert Bigelow, that power could grow.

You see, Bigelow wants to experiment with inflatable habitats that will allow people to live in space. By getting an FAA launch license that gives him access to space, Bigelow would be able to stake out an exclusive piece of the moon.

Space law experts believe that this exclusive territory could be very, very big. That’s because under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, crewed vehicles are entitled to operate inside a 125-mile “non-interference” zone designed to keep astronauts safe, Joanne Gabrynowicz, the former editor of the Journal of Space Law, told Harvard Political Review. If the same standard were applied to commercial space operations on lunar or other extraterrestrial bodies, then Bigelow could become a leader in the first major land rush of outer space.•

Tags: Brian Fung, Robert Bigelow

Like any pioneer in an age of mass media, Sally Ride was asked a lot of dumb questions. She answered them, but not without some consternation.

Ride, who became the first American woman in space in 1983–cosmonaut Valentina Vladimirovna Tereshkova was the first overall twenty years earlier–and passed away in 2012, is the subject of today’s multi-scenario Google Doodle. The opening of “A Ride in Space,” a painfully titled People piece by Michael Ryan which profiled the astronaut as she prepared for her Challenger mission:

JOHNSON SPACE CENTER

This is the hero factory. In this network of squat gray bunkers set apart from downtown Houston by a freeway, a side road and two speed traps, the likes of Alan Shepard, Gus Grissom, John Glenn and Neil Armstrong were introduced to the world and transformed from men into legends. Today’s reusable space shuttle may be less exotic than the old space capsules; still, as NASA demonstrated on one steamy Texas afternoon a few weeks ago, it can still make an astronaut into a household name. Case in point: Sally Kristen Ride, mission specialist on this week’s scheduled flight of the shuttle Challenger and the first American woman in space.

“This mission has a lot of historic firsts,” NASA spokesman John Lawrence coyly announced as the session began. But the television crews and tourists had not convened to hear about Indonesia’s new communications satellite, or the radish seed experiment designed by two Cal Tech students and placed on the shuttle by the largesse of movie wizard Steven Spielberg. All eyes brushed past shuttle commander Robert Crippen, Capt. Rick Hauck and crew members John Fabian and Norm Thagard. Instead, they focused on Ride, 32, the living proof that the Brotherhood of the Right Stuff is now admitting sisters.

No other astronaut was ever asked questions like these: Will the flight affect your reproductive organs? The answer, delivered with some asperity: “There’s no evidence of that.” Do you weep when things go wrong on the job? Retort: “How come nobody ever asks Rick those questions?” Will you become a mother? First an attempt at evasion, then a firm smile: “You notice I’m not answering.” In an hour of interrogation that is by turns intelligent, inane and almost insulting, Ride remains calm, unrattled and as laconic as the lean, tough fighter jockeys who surround her. “It may be too bad that our society isn’t further along and that this is such a big deal,” she reflects.

No American ever had more of the makings of an astronaut than Sally Ride. A California teenage tennis champion who flirted with turning pro, she started college at Swarthmore and transferred to Stanford. She earned two bachelor’s degrees: English, because Shakespeare intrigued her; physics, because lasers fascinated her. As she soars through the empyrean, television commentators will make her résumé familiar to the world: Ph.D., astrophysics, Stanford. Astronaut training, 1978. Capsule communicator—the crucially important link between Mission Control and spacecraft—for shuttles 2 and 3. She married astronaut Steve Hawley, 32, last July. She flew her own plane to the wedding at his parents’ home in Kansas.

This much is known of her life, but much more is unknown—and she aims to keep it that way. Ride and Hawley (who is scheduled to fly next March) avoid appearing together in public. They bar the press from their home in a suburban development near NASA. Sally Ride is not the sort of person about whom anecdotes cluster. She is an indifferent housekeeper—a genetic inheritance, perhaps, from an insouciant, good-humored mother who allowed her daughters to buy a collie only after carpeting the house in collie colors to make the dog’s shedding less obvious. She is certainly a remarkable athlete. When a high school science teacher once attempted to demonstrate the difference between resting pulse and exercising pulse by measuring Sally’s heart rate before and after she ran around the campus, the two rates were almost identical. She is also not without quirks—she firmly believes that Anacin tablets go down more easily when the little arrow imprinted on them is pointed toward the back of the throat. That superstition Sally laughingly ascribes to overexposure to the humanities while in college.

Ride considers herself an astronaut and a scientist—and she has little use for reporters who try to transform her into a celebrity. “They seem to ask the same stupid questions,” her sister, Karen, observes. “Sally has an obvious impatience for that.”•

Tags: Michael Ryan, Sally Ride, Steve Hawley

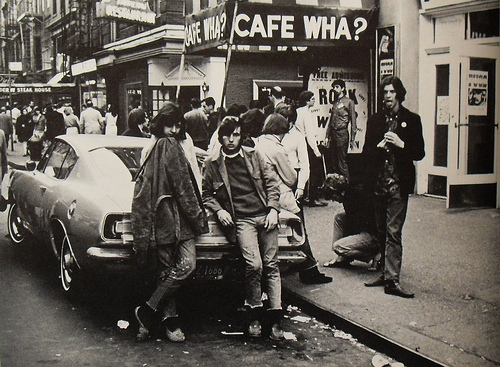

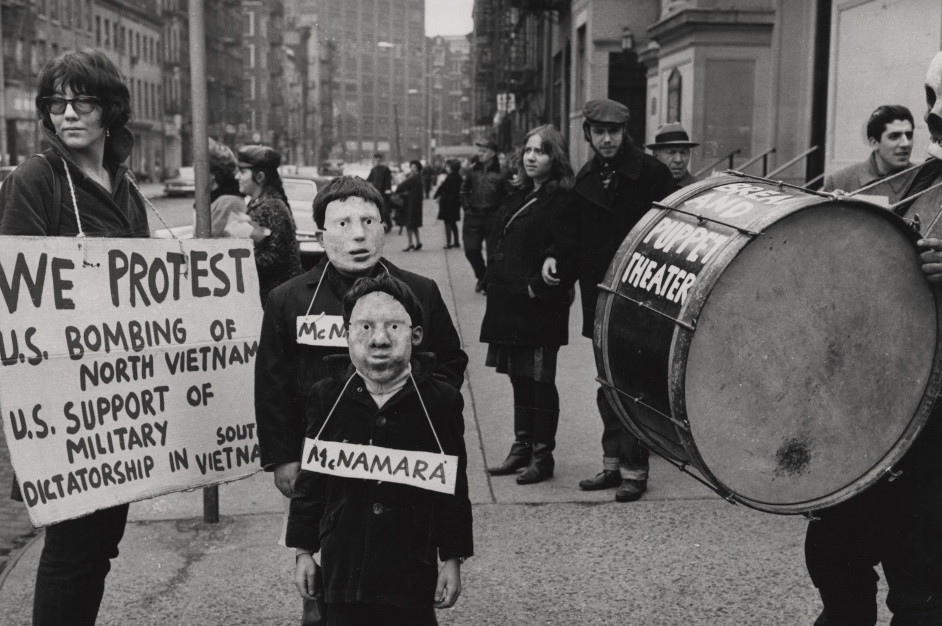

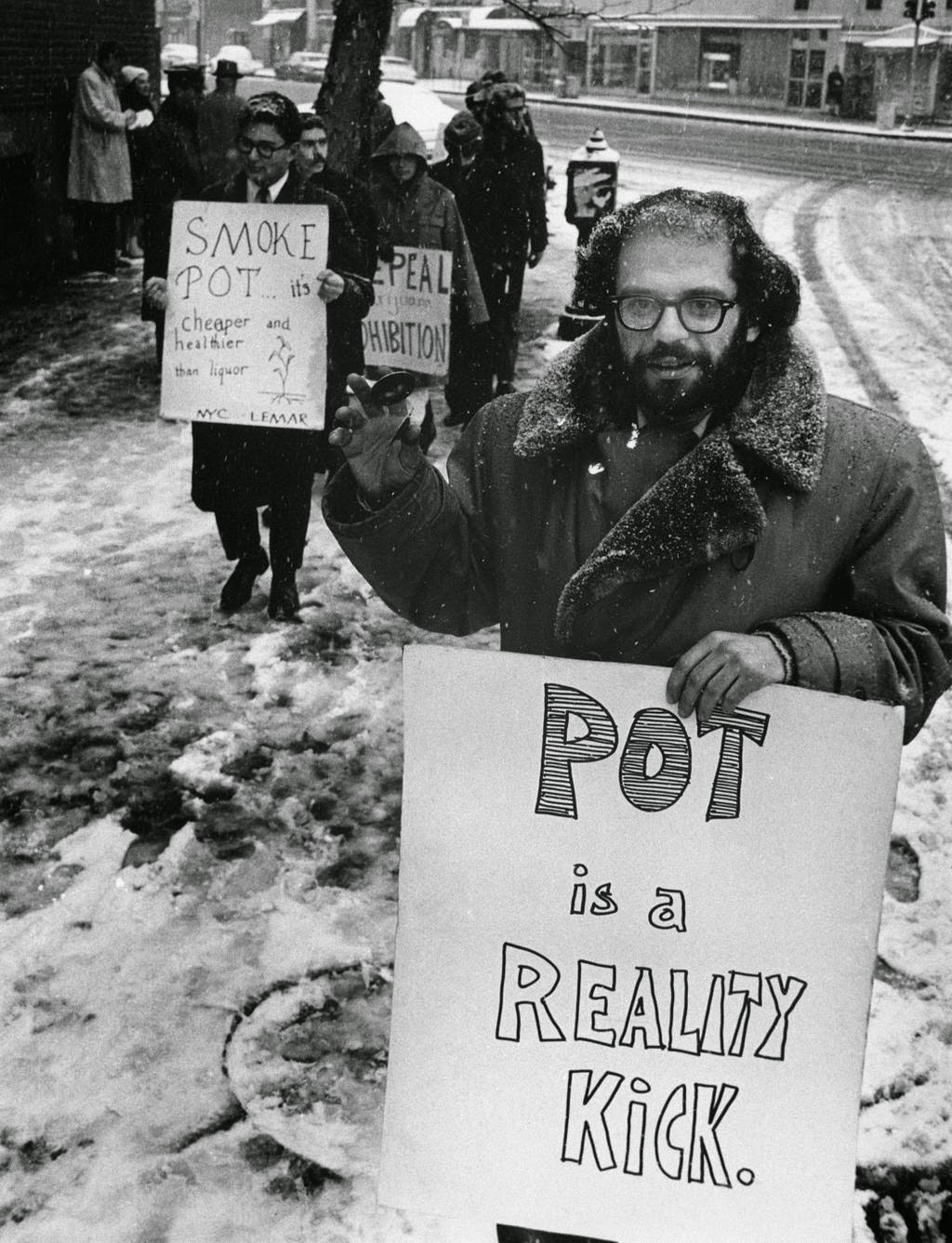

A couple years before Michael Herr began writing his amazing Vietnam reportage for Esquire–an experience which later served as the basis for his great book Dispatches—the journalist penned “Bleecker Street: Bohemia’s Barometer,” a 1965 piece for Holiday magazine about his New York City neighborhood of Greenwich Village. He knew the community of that era as a tale of two cities, a divide among bewildered locals and invading “barbarians.” Herr, who turned 75 last month, also famously co-wrote the screenplay for Full Metal Jacket with his longtime friend Stanley Kubrick. Two excerpts from Holiday follow.

_______________________________

Between this corner and the Bowery, Bleecker Street is like a river running into swamp, block after block with no definable character. It is neither market nor tenement nor warehouse district, but a nondescript mixture of these, with a few grimy luncheonettes and some slum lofts thrown in: a vacuum. A walk down this end of Bleecker is an exercise in induced despair, emotional slumming. The cityscape here is so desolate that it becomes surreal. You feel that behind the brick building fronts there is nothing but emptiness, fixtures connecting nothing to nothing, stairs leading up to doors that open onto a void. At Crosby you come to the Bayard Building, the only work of Louis Sullivan that is left in New York. The façade, particularly in this setting, is magnificent. Beyond it, a two-minute walk will put you on the Bowery, where nothing ever changes.

By the press, the politicians, the police and the populace, Bleecker Street has been called practically everything: a “hotbed of incipient violence,” a slum, a honkytonk, a refuge for homosexuals and/or miscegenists, a hangout for beatniks and commies and dope fiends, a shameless tourist trap. But whatever it may or may not be, whatever strange flavors outsiders bring to it, Bleecker is primarily, prevailingly Italian.

There is an old blind man who sits in the afternoons near the corner at Sixth Avenue. He told me once that he has never left Naples. He sits close enough to the Hudson to smell the harbor, and all around him are the aromas of new produce, olive oil, fennel, roasting coffee and freshly killed meat. At least as much Italian is being spoken as English.

Bleecker Street days are not much like Bleecker Street nights. Afternoons are taken up by the business of the neighborhood: the schooling and recreation of children, the purchase of groceries, the delivery of commodities to fifty shops and stalls up and down the street. Whatever social life the older residents have is conducted on these sidewalks during daylight hours, when the sidewalks are still theirs.

On these afternoons there is a moon-faced woman in black polka-dotted housedress who leans on a crate of fresh plums, gesturing to customers over baskets of grapes. Her prices are marked, but she will tolerate a limited amount of bargaining. Some of this bargaining has gone on between her and the same customers for over twenty years. Up the street some old men in shirtsleeves stand in front of Ruggiero’s Fish Market, lunching on oysters from a card table set up on the sidewalk. They prepare each one separately, adding hot sauce and lemon. A Negro workman comes up to the table, and the old men throw down some coins and leave. At the corner, one of them mutters, “Mulignam!” a dialect expression for eggplant, which is also their pejorative for Negroes. Then they cross the street to Father Demo Square. Of course the Negro knows what has happened.

This parade route for visiting liberals. anarchists, socialists, apolitical grousers, peace marchers and civil-rights workers is also a neighborhood of Ghibelline rigidity, prejudice, reaction. Not long ago the Carmine DeSapio sound trucks cruised along here begging votes in blaring Calabrese dialect. Now you can see the remains of a Goldwater poster peeling to reveal the spattered likeness of De Sapio oil brick walls at street corners, and the traditional Democratic block is finished. The mounting tourist traffic is an outrage to the residents, particularly among first-generation immigrants. For them, the thought of miscegenation is unbearable, and you can feel the hatred this generates up and down the length of the street. Some of the locals have turned this influx to their advantage, opening bars, restaurants and galleries, but most sit locked in severe parochial resentment. If the Evil Eye really worked, the sidewalks would be strewn with paralytics, heaped with the blind and the dead.

_______________________________

They call MacDougal “the Mess,” and not without reason. In summer, at the corner where it crosses Bleecker, the sidewalks are clogged every night of the week. During the rest of the year the crowds come only on weekends, but they come in such numbers that they make up for the Monday-through-Thursday calm. No one knows exactly what brings them or who they are or even who they think they are, but there are a lot of them. The word is out that this is Where It’s At. As usual, the word lies, but none of the thousands, the tens of thousands, who come here night after night will ever admit it.

Most of them are young, under twenty, of a type that used to be written of as “beatnik.” But that word hasn’t meant anything for years, and it certainly doesn’t apply to this crowd. These are cultists whose beliefs are murky, a whole generation sprung half-baked from a badly digested notion of Bohemia, malnurtured on mass-media accounts of groovy goings-on from Liverpool to Berkeley. What they appear to want, more than anything else, is to enchant, but there never seem to be any takers. They are the sons and daughters of Tarrytown orthodontists, Rochester retailers, Long Island manufacturers, Jersey City construction workers, all come to conduct one of the most elaborate flirtations in history. And they are not the only ones; their parents come, too, impeccably polished. expensively dressed, and they come for almost the same reason. Everyone wants his slice of hip cake.

Once, it was the bourgeoisie’s had joke to say they couldn’t tell the boys from the girls. but this is no longer a joke. Young men, apparently not homosexual, wear their hair shoulder-length: if it were cleaner you might say it flowed. It is a part of the fashion, and the MacDougal-Bleecker crowd pays careful attention to fashion. The real hippies have been forced into coats and ties, now that their old turf has been overrun by creeps.

It was the fashion, for several weeks last spring, for girls to walk along Bleecker carrying a single flower. If they could get nothing better, they would carry a plastic flower, but there were dozens of these girls with their flowers. That ended. They turned up wearing those Liverpool sailors’ hats. And little white ankle boots. Then bellbottomed denim slacks with broad-striped jerseys worn loose around the waist. On dress occasions they wore discotheque dresses and patterned stockings that made the skin on their legs look diseased. Then the boys began wearing watch caps—hadn’t the Beatles introduced them?—and a few even started wearing the slacks. The esoterics, gurus and prep-school liberals took to wearing rimless glasses, often with hexagonal lenses, and with the glasses came effete Danish pipes, and floppy felt hats like the ones W. B. Yeats used to wear—all kinds of Yellow Bookish paraphernalia. Fashion. And they come down here to parade all this, each one sure that the Village has never seen anything like it.

After dark the sidewalks become so crowded that you have to take odd little two-inch steps or else walk around the cars, police and motorcycles in the street. If you have had the practice you can discern the slightest trace of marijuana in the air, although they say that it is only Sano cigarette smoke. There is usually music, either from a passing folkie or from a transistor radio.

There is a folksong that goes:

When I die please bury me deep,

Down at the end of Bleecker Street,

So I can hear old Number Nine,

As she goes rolling by.

I can’t find out what this really means.•

Tags: Michael Herr

Paul Krugman’s New York Times column addresses the puzzling state of contemporary economics, suggesting the impact of the new technologies on production has been grossly overstated. That might be true. Really smart people have been convinced of completely wrong things before, and Silicon Valley’s effect on the bottom line might just be the latest example. Or maybe, as Krugman acknowledges, we’re only in the prelude of the big change or perhaps the current equations aren’t sufficient to capture the new normal.

The one thing I’ll add is that automation probably can be a big deal for the economy in another sense, even if it doesn’t promote a sea change in production. Apps and automated workplaces don’t necessarily have to hugely increase production to completely obviate workers. It could be an even exchange of computers supplanting labor, torpedoing traditional industries while turning out similar products and services–think Uberization–though who will be able to afford them is the question.

From Krugman:

One possibility is that the numbers are missing the reality, especially the benefits of new products and services. I get a lot of pleasure from technology that lets me watch streamed performances by my favorite musicians, but that doesn’t get counted in G.D.P. Still, new technology is supposed to serve businesses as well as consumers, and should be boosting the production of traditional as well as new goods. The big productivity gains of the period from 1995 to 2005 came largely in things like inventory control, and showed up as much or more in nontechnology businesses like retail as in high-technology industries themselves. Nothing like that is happening now.

Another possibility is that new technologies are more fun than fundamental. Peter Thiel, one of the founders of PayPal, famously remarked that we wanted flying cars but got 140 characters instead. And he’s not alone in suggesting that information technology that excites the Twittering classes may not be a big deal for the economy as a whole.

So what do I think is going on with technology? The answer is that I don’t know — but neither does anyone else. Maybe my friends at Google are right, and Big Data will soon transform everything. Maybe 3-D printing will bring the information revolution into the material world. Or maybe we’re on track for another big meh.

Tags: Paul Krugman

Muammar Gaddafi got what he deserved, but so few do.

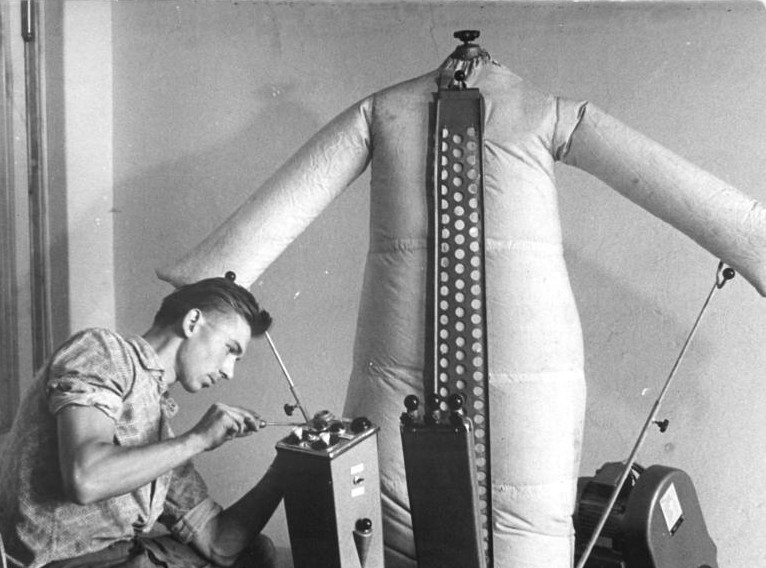

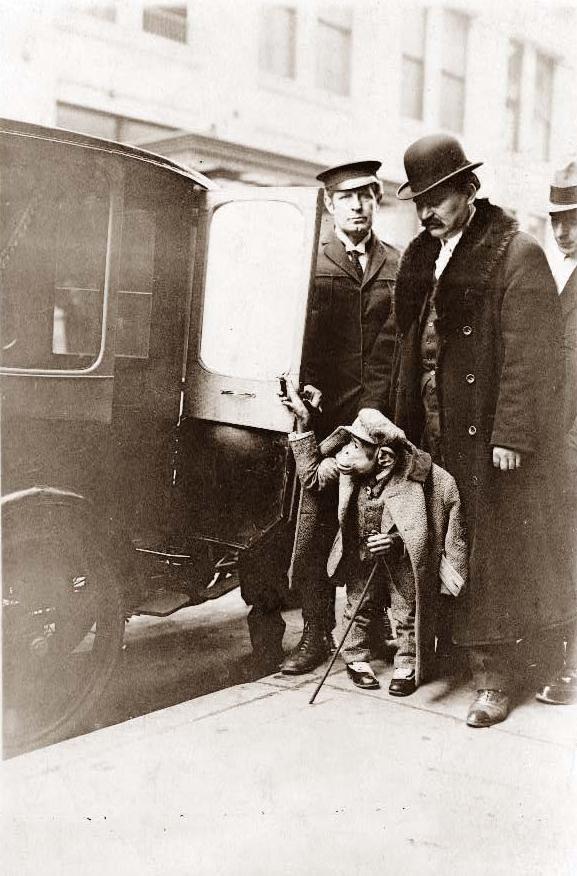

Wernher von Braun, Nazi scientist, warranted a hanging for his crimes against humanity, but he had a talent considered crucial during the early stages of the Cold War, so his past was whitewashed, and he was installed as the leader of NASA’s space program, ultimately becoming something of an American hero. So very, very unfair.

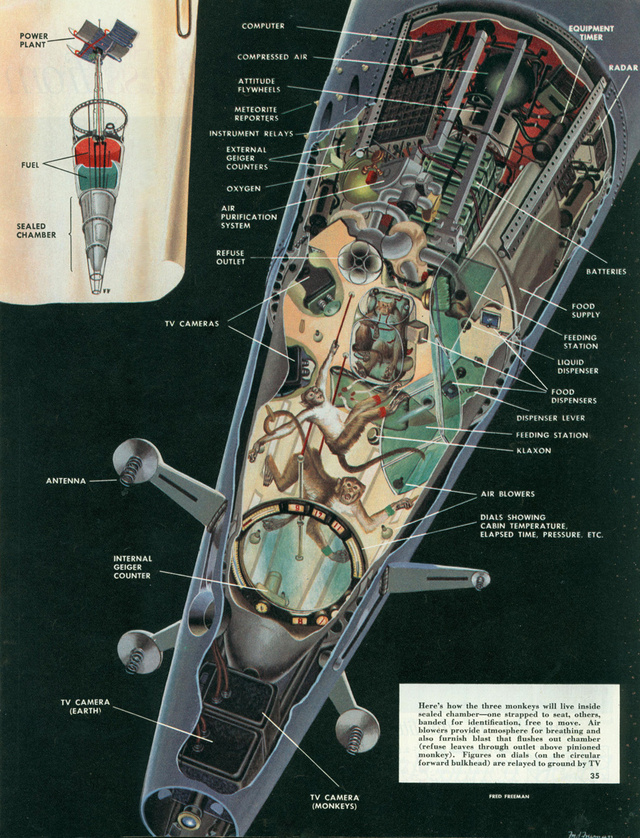

But his horrific past in Germany bled over into his new one in the U.S. in his early ’50s plan to send a “baby satellite” into space for two months with a crew of three rhesus monkeys. The mission completed, the rocket would burn up as it reentered the atmosphere. To save the primates from the pain of an inferno, Braun wanted to create an automatic switch which would gas the monkeys to death–yes, a gas chamber in space. “The monkeys will die instantly and painlessly,” he wrote in a 1952 Collier’s article he co-authored with Cornelius Ryan. It staggers the mind.

The article:

WE ARE at the threshold today of our first bold venture into space. Scientists and engineers working toward man’s exploration of the great new frontier know now that they are going to send aloft a robot laboratory as the first step—a baby space station which for 60 days will circle the earth at an altitude of 200 miles and a speed of 17,200 miles an hour, serving as scout for the human pioneers to follow.

We rocket engineers have learned a lot about space by shooting off the high-flying rockets now in existence—so much that right now we know how to build the rocket ships and the big space station we need to put man into space and keep him there comfortably. We know how to train space crews and how to protect them from the hazards which exist above our atmosphere. All that has been reported in previous issues of Collier’s.

But the rockets which have gathered our data have stayed in space for only a few minutes at a time. The baby satellite will give us 60 days; we’ll learn more in those two months than in 10 years of firing the present instrument rockets.

We can begin work on the new space vehicle immediately. The baby satellite will look like a 30-foot ice-cream cone, topped by a cross of curved mirrors which draw power from the sun. Its tapered casing will contain a complicated maze of measuring instruments, pressure gauges, thermometers, microphones and Geiger counters, all hooked up to a network of radio, radar and television transmitters which will keep watchers on earth informed about what’s going on inside it.

Speeding 30 times faster than today’s best jets, the little satellite will make one circuit around the earth every 91 minutes—nearly 16 round trips a day. At dawn and dusk it will be visible to the naked eye as a bright, unwinking star, reflecting the sun’s rays and traveling from horizon to horizon in about seven minutes. Ninety-one minutes later, it completes the circuit—but if you look for it in the same place, it won’t be there: it travels in a fixed orbit, while the earth, rotating on its own axis, moves under it. An hour and a half from the time you first sighted the speeding robot, it will pass over the earth hundreds of miles to the west. The cone will never be visible in the dark of night, because it will be in the shadow of the earth.

If you live in Philadelphia, one morning you may see the satellite overhead just before sunup, moving on a southeasterly course. Ninety-one minutes later, as dawn breaks over Wichita, Kansas, people there will see it, and after another hour and a half it will be visible over Los Angeles—again, just before the break of dawn.

That evening, Philadelphians—and the people of Wichita and Los Angeles—will see the speeding satellite again, this time traveling in a northeasterly direction. The following morning, it will be in sight again over the same cities, at about the same time, a little farther to the west.

After about ten days, it will no longer appear over those three cities, but will be visible over other areas. Thus, from any one site, it will be seen on successive occasions for about 20 days before disappearing below the western horizon. In another month or so, it will show up again in the east. And while you’re gazing at the little satellite, it will be peering steadily back, through a television camera in its pointed nose. The camera will give official viewers in stations scattered around the globe the first real panoramic picture of our world—a breath-taking view of the land masses, oceans and cities as seen from 200 miles up. More than likely, commercial TV stations will pick up the broadcasts and relay them to your home.

Three more cameras, located inside the cone, will transmit equally exciting pictures: the first sustained view of life in space.

Three rhesus monkeys—rhesus, because that species is small and highly intelligent—will live aboard the satellite in air-conditioned comfort, feeding from automatic food dispensers. Every move they make will be watched, through television, by the observers on earth.

As fast as the robot’s recording instruments gather information, it will be flashed to the ground by the same method used now in rocket-flight experiments. The method is called telemetering, and it works this way: as many as 50 reporting devices are hooked to a single transmitter which sends out a jumble of tonal waves. A receiver on earth picks up the tangled signals, and a decoding machine unscrambles the tones and prints the information automatically on long strips of paper, as a series of spidery wavelike lines. Each line represents the findings of a particular instrument—cabin temperature, air pressure and so on. Together, they’ll provide a complete story of the happenings inside and outside the baby space station.

What kind of scientific data do we hope to get? Confirmation of all space research to date and, most important, new information on weightlessness, cosmic radiation and meteoric dust.

At a high enough speed and a certain altitude, an object will travel in an orbit around the earth. It— and everything in it—will be weightless. Space scientists and engineers know that man can adjust to weightlessness, because pilots have simulated the condition briefly by flying a jet plane in a rollercoaster arc. But will sustained weightlessness raise problems we haven’t foreseen? We must find out—and the monkeys on the satellite will tell us.

The monkeys will live in two chambers of the animal compartment. In the smaller section, one of the creatures will lie strapped to a seat throughout the two-month test. His hands and head will be free, so he can feed himself, but his body will be bound and covered with a jacket to keep him from freeing himself or from tampering with the measuring instruments taped painlessly to his body. The delicate recording devices will provide vital information—body temperature, breathing cycle, pulse rate, heartbeat, blood pressure and so forth.

The other two monkeys, separated from their pinioned companion so they won’t turn him loose, will move about freely in the larger section. During the flight from earth, these two monkeys will be strapped to shock-absorbing rubber couches, under a mild anesthetic to spare them the discomfort of the acceleration pressure. By the time the anesthetic wears off, the robot will have settled in its circular path about the earth, and a simple timing device will release the two monkeys. Suddenly they’ll float weightless, inside the cabin.

What will they do? Succumb to fright? Perhaps cower in a corner for two months and slowly starve to death? I don’t think so. Chances are they’ll adjust quickly to their new condition. We’ll make it easier for them to get around by providing leather handholds along the walls, like subway straps, and by stringing a rope across the chamber.

There’s another problem for the three animals: to survive the 60 days they must eat and drink.

They’ll prepare to cope with that problem on the ground. For months before they take off, the two unbound monkeys will live in a replica of the compartment they’ll occupy in space, learning to operate food and liquid dispensers. In space, each of the two free animals will have his own feeding station. At specific intervals a klaxon horn will sound; the monkeys will respond by rushing to the feeding stations as they’ve been trained to do. Their movement will break an electric-eye beam, and clear plastic doors will snap shut behind them, sealing them off from their living quarters. Then, while they’re eating, an air blower will flush out the living compartment—both for sanitary reasons and to keep weightless refuse from blocking the television lenses. The plastic doors will spring open again when the housecleaning is finished.

The monkeys will drink by sucking plastic bottles. Liquid left free, without gravity to keep it in place, would hang in globules. To get solid food, each of the monkeys—again responding to their training—will press a lever on a dispenser much like a candy or cigarette machine. The lever will open a door, enabling the animals to reach in for their food. They’ll get about half a pound of food a day—a biscuit made of wheat, soybean meal and bone meal, enriched with vitamins. The immobilized monkey will have the same food; his dispensers will be within easy reach.

For the two free monkeys, it will be a somewhat complicated life. The way they react to their ground training under the new conditions posed by lack of gravity will provide invaluable information on how weightlessness will affect them.

While the monkeys are providing physiologists with information on weightlessness, physicists will be learning more about cosmic rays, invisible high-speed atomic particles which act like deep penetrating X rays and were once feared as the major hazard of space flight. Theoretically, in large enough doses cosmic rays could conceivably cause deep burns, damage the eyes, produce malignant growths and even upset the normal hereditary processes. They don’t do much damage to us on earth because the atmosphere dissipates their full strength, but before much was known about the rays people worried about the dangers they might pose to man in space. From recent experiments scientists now know that the risk was mostly exaggerated—that even beyond the atmosphere a human can tolerate the rays for long periods without ill effects. Still, the best figures available have been obtained by high-altitude instrument rocket flights which were too brief to be conclusive. These spot checks must be augmented by a prolonged study, and the baby space station will make that possible.

The concentration of cosmic rays over the earth varies, being greatest over the north and south magnetic poles. The baby space station will follow a circular path that will carry it close to both poles within every hour and a half, so it can determine if cosmic-ray concentration varies that high up.

Geiger counters inside and outside the robot will measure the number of cosmic particle hits. The telemetering apparatus will signal the information to the ground—and for the first time physicists will have an accurate indication of the cosmic-ray concentration in space, above all parts of the globe.

Besides cosmic rays, the baby satellite will be hit by high-speed space bullets—tiny meteors, most of them smaller than a grain of sand, whizzing through space faster than 1,000 miles a minute.

When men enter space, they’ll be protected against these pellets. Their rockets, the big space station, even their space suits, will have an outer skin called a meteor bumper, which will shatter the lightning-fast missiles on impact. But how many grainiike meteors must the bumpers absorb every 24 hours? That’s what we space researchers want to know. So dime-sized microphones will be scattered over the robot’s outer skin to record the number and location of the impacts as they occur.

In the process of unmasking the secrets of space, the baby satellite also will unravel a few riddles of our own earth.

For example, there are numerous islands whose precise position in the oceans has never been accurately established because there is no nearby land to use as a reference point. Some of them—one is Bouvet Island, lying south of the Cape of Good Hope—have been the subject of international disputes which could be quickly settled by fixing the islands’ positions. By tracking the baby space station as it passes over these islands, we’ll accurately pinpoint their locations for the first time.

The satellite will be even more important to meteorologists. The men who study the weather would like to know how much of the earth is covered with cloud in any given period. The robot’s television camera will give them a clue—a start toward sketching in a comprehensive picture of the world’s weather. Moreover, by studying the pattern of cloud movement, particularly over oceans, they may learn how to predict weather fronts with precision months in advance. Most of the weather research must await construction of a man-carrying space station, but the baby satellite will show what’s needed.

To collect this information, of course, we must first establish the little robot in its 200-mile orbit. All the knowledge needed for its construction and operation is already available to experts in the fields of rocketry, television and telemetering.

Before take-off, the satellite vehicle will resemble one of today’s high-altitude rockets, except that it will be about three times as big—150 feet tall, and 30 feet wide at the base. After take-off it will become progressively smaller, because it actually will consist of three rockets—or stages—one atop another, two of which will be cast away after delivering their full thrust. The vehicle will take off vertically and then tilt into a shallow path nearly parallel to the earth. Its course will be over water at first, so the first two stages won’t fall on anyone after they’re dropped, a few minutes after take-off.

When the third stage of the vehicle reaches an altitude of 60 miles and a speed of 17,700 miles an hour, the final bank of motors will shut off automatically. The conical nose section will coast unpowered to the 200-mile orbit, which it will reach at a speed of 17,100 miles an hour, 44 minutes later. The entire flight will take 48 1/2 minutes.

After the satellite reaches its orbit, the automatic pilot will switch on the motors once again to boost the velocity to 17,200 miles an hour—the speed required to balance the earth’s gravity at that altitude. Now the rocket becomes a satellite; it needs no more power but will travel steadily around the earth like a small moon for 60 days, until the slight air drag present at the 200-mile altitude slows it enough to drop.

Once the satellite enters its orbit, gyroscopically controlled flywheels cartwheel the nose until it points toward the earth. At the same time, five little antennas spring out from the cone’s sides and a small explosive charge blasts off the nose cap which has guarded the TV lens during the ascent.

Finally, the satellite’s power plant—a system of mirrors which catch the sun’s rays and turn solar heat into electrical energy—rises into place at the broad end of the cone. A battery-operated electric timer starts a hydraulic pump, which pushes out a telescopic rod. At the end of the rod are the three curved mirrors. When the rod is fully extended, the mirrors unfold, side by side, and from the ends of the central mirror two extensions slip out. Mercury-filled pipes run along the five polished plates; the heated mercury will operate generators providing 12 kilowatts of power. Batteries will take over the power functions while the satellite is passing through the shadow of the earth.

With the power plant in operation, the baby space station buckles down to its 60-day assignment as man’s first listening post in space.

At strategic points over the earth’s surface, 20 or more receiving stations, most of them set up in big trailers, will track the robot by radar as it passes overhead, and record the television and telemetering broadcasts on tape and film. Because the satellite’s radio waves travel in a straight line, the trailers can pick up broadcasts for just a few minutes at a time—only while the robot remains in sight as it zooms from horizon to horizon.

As the satellite passes out of range, the recorded data will be sent to a central station in the United States—some of it transmitted by radio, the rest shipped by plane. There, the information will be evaluated and integrated from day to day.

The monitoring posts will be set up inside the Arctic and Antarctic Circles and at points near the equator. In the polar areas, stations could be at Alaska, southern Greenland and Iceland; and in the south, Shetland Islands, Campbell Island and South Georgia Island. In the Pacific, possible sites are Baker Island, Christmas Island, Hawaii and the Galapagos Islands.

The remaining monitors may be located in Puerto Rico, Bermuda, St. Helena, Liberia, South-West Africa, Ethiopia, Maldive Islands, the Malay Peninsula, the Philippines, northern Australia and New Zealand. These points, all in friendly territory, would form a chain around the earth, catching the satellite’s broadcasts at least once a day.

The monitor stations will be fairly costly, but they’ll come in handy again later, when man is ready to launch the first crew-operated rocket ships for development of a big-manned space station, 1,075 miles from the earth.

The cost of the baby satellite project will be absorbed into the four-billion-dollar 10-year program to establish the bigger satellite. We scientists can have the baby rocket within five to seven years if we begin work now. Five years later, we could have the manned space station.

One of the monitoring posts will view the last moments of the baby space station. As the weeks pass, the satellite, dragging against the thin air, will drop lower and lower in its orbit. When it descends into fairly dense air, its skin will be heated by friction, causing the temperature to rise within the animal compartments. At last, a thermostat will set off an electric relay which triggers a capsule containing a quick-acting lethal gas. The monkeys will die instantly and painlessly. Soon afterward, the telemetering equipment will go silent, as the rush of air rips away the solar mirrors which provide power, and the baby space station will begin to glow cherry red. Then suddenly the satellite will disappear in a long white streak of brilliant light—marking the spectacular finish of man’s first step in the conquest of space.•

Tags: Cornelius Ryan, Wernher von Braun

As usual, Christopher Mims gets to the heart of the matter in his latest WSJ column, this one about the so-called Sharing Economy, in which little or nothing is shared, the only real change being jobs destabilized by businesses that are pure app and no inventory. It’s a Libertarian dream, a market with fungible, low-paid workers and no nets, and you, rabbit, had better get used to your task because it’s fractional employment and you are a very common denominator.

Mims wonders how this new breed of workers will ultimately be classified and whether an eventual class-action lawsuit could kill the category, though I if I had to bet, I would guess that’s not how things unfold.

An excerpt:

The first thing everyone misses about the sharing economy is that there is no such thing, not even if we’re being semantically charitable. Increasingly, the goods being “shared” in the sharing economy were purchased expressly for business purposes, whether it’s people renting apartments they can’t afford on the theory that they can make up the difference on Airbnb, or drivers getting financing through partners of ride-sharing services Uber and Lyft to get a new car to drive for those same services.

What’s more, many of the companies under this umbrella, like labor marketplace TaskRabbit, don’t involve “sharing” anything other than labor. If TaskRabbit is part of the sharing economy, then so is every other worker in America. The only thing these companies have in common is that they are all marketplaces, though they differ widely in the amount of control they give their buyers and sellers.

In the minds of critics, perhaps the worst offender in how it controls its labor force is Uber. Uber sets the prices that its drivers must accept, and has lately been in the habit of unilaterally squeezing drivers in two ways, both by lowering the rates drivers are paid per trip and increasing Uber’s cut of those wages. Behavior like this has led to some pretty overheated but not entirely undeserved rhetoric.•

Tags: Christopher Mims

Some Silicon Valley employees save time by skipping solid food, instead slurping Soylent or Schmoylent or Schmilk or Schcum (made up the last one), protein powders containing essential vitamins which are mixed with water or milk. Certainly, it’s unnecessary. It doesn’t take any more time to pack light, healthy foods, but subcultures have their own viral trends, and sometimes good can come of them. Think Los Angeles in the ’60s and ’70s with health food and exercise. But perhaps these coders and venture capitalists might consider that teeth and jaws and stomachs benefit from the biting, chewing and digesting of solids.

From Brian X. Chen of the New York Times:

SAN FRANCISCO — Every night, Aaron Melocik, a software developer, follows a precise food routine. He blends together half a gallon of water, three and a half tablespoons of macadamia nut oil and a 16-ounce bag of powder called Schmoylent. Then he pours the beige beverage into jars and chills them before bringing the containers to work the next day at Metrodigi, an education technology start-up.

At the office, Mr. Melocik stashes one Schmoylent jar in the refrigerator and takes the other to his desk. From 6:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m., he sips from the first jar for breakfast, and the second for lunch. He consumes about 14 fluid ounces of Schmoylent each day so he can focus on coding instead of grabbing a bite to eat.

“It just removes food completely from my morning equation up until about 7 p.m.,” said Mr. Melocik, 34, who has been following his techie diet since February.

Boom times in Silicon Valley call for hard work, and hard work — at least in technology land — means that coders, engineers and venture capitalists are turning to liquid meals with names like Schmoylent, Soylent, Schmilk and People Chow. The protein-packed products that come in powder form are inexpensive and quick and easy to make — just shake with water, or in the case of Schmilk, milk. While athletes and dieters have been drinking their dinner for years, Silicon Valley’s workers are now increasingly chugging their meals, too, so they can more quickly get back to their computer work.•

Tags: Aaron Melocik, Brian X. Chen

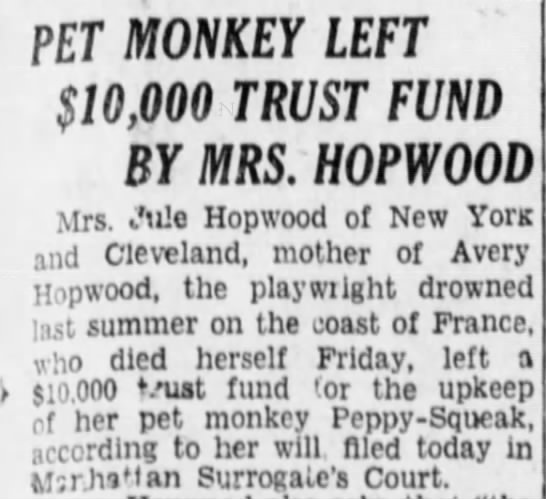

Tags: Mrs. Jule Hopwood, Peppy-Squeak

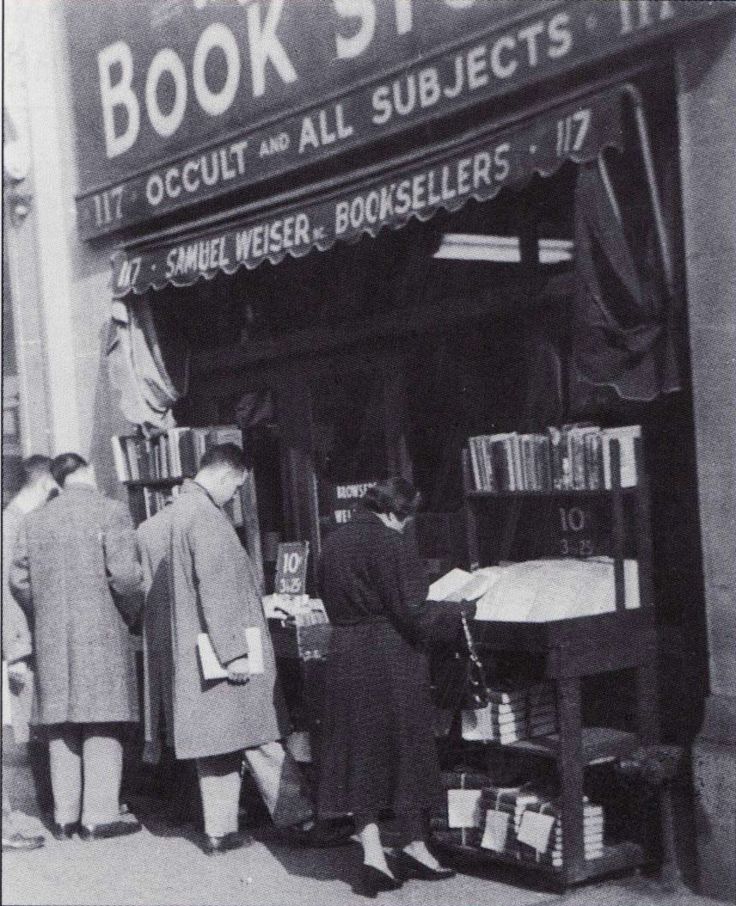

It’s not that I’ve learned to stop worrying and love the bomb, but I’m not nearly as concerned about the future of books as I was only a couple of years ago.

I certainly don’t think Amazon should be setting online book prices, and if it reaches monopoly level (and it may have already), that should be addressed on a federal level. I say that as someone who isn’t an Amazon hater. No company has made reading such a full and diverse experience.

There are so many great books being published now that I can’t even begin to keep up with them. That wasn’t supposed to happen as screens shrunk, publishers were pummeled, bricks and mortars were dismantled and libraries cut hours.

I grew up in a neighborhood without a bookstore, and if I had then had a Kindle and an Amazon Prime membership, I would have had access to the most amazing collection of volumes in the history of the world. That was never possible before the Internet.

While books are more widely available than ever before, they’re certainly less visible offline. That could be remedied on a local level if small shops were incentivized with government funds, the way NYC does with supermarkets that sell sections of healthy food in poorer neighborhoods which don’t already have easy access to fresh produce. (Of course, these markets haven’t changed eating habits.)

So, I suppose I’m much more sanguine about the present and future of reading in the U.S. (or at least the opportunity to read) than Scott Timberg of Salon, who feels there must be serious intervention to save our literary culture. From Timberg:

It’s always good news when a bookstore opens, and when it’s an indie backed with significant amounts of cash, and run by someone who really cares, it’s even better. So like everyone else, we smiled when we saw the New York Times story about Diary of a Wimpy Kid author Jeff Kinney — whose series “has spawned three feature films that have earned more than $225 million worldwide” — opening a bookstore in Plainville, Mass. Like Parnassus, the shop novelist Ann Patchett co-owns in Nashville, this will allow people to stumble upon books they’d never thought of looking at, it will employ booklovers behind the counter, and will hold events that allow authors to reach readers. All good things.

But it also makes us wonder: In the Age of Amazon, are the only people who can open bookstores celebrity authors? And aren’t these cheery stories about these mostly anomalous events kind of distracting us from the big picture? …

But isn’t this a bit like the benefit concerts that we threw for ailing and dying musicians back in the days before national medical insurance? The fact that Victoria Williams, Vic Chetnutt and Alejandro Escovedo came close to dying because they lived in a country that denied people basic health coverage was the original sin – and larger context — there. Musicians and fans worked hard to apply a (much needed) band-aid with Sweet Relief concerts and the like. But in the long run we needed a broader safety net, not more passing of the hat.

So what’s the larger context here? Well, if you follow the conversation as it’s expressed by bookstore organizations and the Times story, everything is fine: Indies are bouncing back, and some really cool authors are opening new stores! But somehow the Times piece neglects to use the term “online bookselling” or name Amazon even once, or to mention that there are approximately half the number of indies now than there were in the ‘90s, even as we’ve added more than 60 million people to U.S. population since then.•

Tags: Scott Timberg

Not only are car dealers and renters challenged by GetAround, the new Airbnb-ish app that allows you to loan out your vehicle by the hour for a fee, but just imagine what the service will do, should it become successful, to no-tell motels and sex clubs. You know that new car smell? That will be gone.

Like much of the Peer Economy, it’s probably better for consumers and the environment, though it’s likely damaging to industries that actually provide solid jobs.

From Matt McFarland at the Washington Post:

For D.C. residents concerned that they won’t make enough income, GetAround is guaranteeing income of $1,000 in the first three months. Cars must have fewer than 125,000 miles and can’t be more than 10 years old. GetAround provides insurance for drivers during the rental period.

District resident Tara Boyle, 29, began renting her Mazda3 for $8 an hour a couple of weeks ago. Getaround recommended $7.50, but she wanted to charge more. (The $1,000 guarantee requires that you don’t raise your rate more than 20 percent above what Getaround recommends.)

Boyle can walk to work but didn’t want to sell her car, so she jumped at the chance for extra income. She hopes her car will be especially popular with other residents of the high-rise building she lives in. Boyle said she isn’t worried about a renter potentially scuffing up her bumpers during city driving, saying that comes with the territory.

“My dad said, ‘Why do you want to do this? There’s going to be weird people that are sweating in your car,’ ” Boyle said with a laugh. “I said, ‘Dad, a parking spot down here is, like, $200 a month, I want my car to pay for itself.’ ”•

Tags: Matt McFarland, Tara Boyle

Free is expensive, but cheap may be even costlier.

The Freeconomy (Facebook, Google, etc.) will give you stuff you need–or your ego wants–but in return will extract your information. Money isn’t necessary among “friends.” How unseemly. You don’t put a quarter in the slot; the slot just takes what it pleases. These nouveau companies want inside your head, first virtually and eventually literally.

The Cheapoconomy is dicier still. Not only do services like Uber and others track you, but they reduce workers to glorified serfs, promising flexibility for minimal payment, destabilizing more secure industries. As they gain greater power, the laborers will be squeezed more–until they’re completely obliterated. It’s great for us, except if we’re one of them. And more of us in the coming decades will likely become them. We won’t just be the consumers. We’ll be consumed.

The thing is, the Peer Economy (a funny name since the workers are not your equals) is an improvement over the old way when it comes to transportation and delivery services. The disruption was successful because it was, in many ways but not all, good. And that’s where we are, at a strange crossroads of capitalism, libertarianism and socialism. Who can give us a lift out of that neighborhood?

From Douglas Coupland at the Financial Times:

I think right now the Uber situation is like the Teamsters and garburators in the mid-20th century. There’s no real argument to not have Uber drivers. They are superior to taxis in all possible ways. The only thing stopping them are all these cab drivers who had to pay extortionate amounts of money for a medallion, and suddenly entering their arena are these new people with superior service in every way, who also didn’t get hosed buying a medallion (honestly, medallions? How is that even still a thing?). So of course taxi owners are angry, and of course they’re going to lash out and try to generate urban legends to frighten people who, the moment they use an Uber, will never use a taxi again if they don’t have to. Uber’s not alone in this sort of engineered fear environment. Remember the Craigslist killer?

Gosh — someone didn’t buy an ad in a newspaper, and for their stupidity they paid with their life.

And in Canada two weeks ago, the press revelled in the fate of an Edmonton couple who rented out their house on Airbnb, and came back only to find it trashed to the tune of C$100,000. Airbnb now has the largest hotel footprint in the world. Uber has image problems but they’re on the correct historical track. Craigslist, Lyft et al . . . the shareconomy? The freeconomy? It’s going to happen. And the moment these firms start paying more in taxes is the moment they officially suffocate to death the old economy.•

Tags: Douglas Coupland

In 1972, when this variety special was recorded, Bob Hope had already turned into a terrible comedian, but Bobby Fischer was not yet behaving like a terrible person. The chess champ had just “won the Cold War,” besting his Russian counterpart Boris Spassky before the world in a bravura if sometimes bewildering performance. Long before Watson, Fischer was a supercomputer with his wires crossed, unable to conquer just one opponent: himself. While sharing a stage with Hope, he believed he knew what his future held, but he didn’t even know what was lurking inside of himself. Things were going to get strange and stranger.

Tags: Bob Hope, Bobby Fischer