Refuses to leave.

You are currently browsing the archive for the Videos category.

Yikes. It’s like she was drowned and came back to life to avenge her death. (Thanks Reddit.)

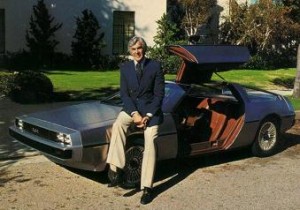

In 1979, John Z. DeLorean was poised for greatness or disaster, having left behind the big automakers to create his own car from scratch, a gigantic gambit that required huge talent and hubris. Esquire writer William Flanagan profiled DeLorean that year, capturing the gambler in mid-deal, still bluffing, soon to be folding. The opening:

“For a man who looks like Tyrone Power, is married to the stunning young model in the Virginia Slims and Clairol ads, and earns six figures a year, John Zachary DeLorean certainly doesn’t smile much. He can’t. Not just yet, anyway. The reason is simple: The most important project in his life has yet to be accomplished. DeLorean wants to make a monkey out of General Motors. He is on the verge of doing it, but he has a way to go.

There will be no rest for DeLorean until he finishes doing what no one else in the history of modern business has dared attempt–to design, build, and sell his very own automobile from scratch, an automobile the world’s largest car company wouldn’t, couldn’t, and probably shouldn’t build.

By mid-1980, either DeLorean will be smiling at last or he’ll be a shattered man. At stake are thousands of jobs for unemployed Catholics in Belfast; the wisdom and reputation of the British government, which, amid howls of protest, has bet about $106 million on the flamboyant engineer; and about another $40 million posted by several hundred U.S. car dealers and other investors, ranging from Merrill Lynch stockbrokers to Johnny Carson.

But most important, John DeLorean’s pride is at stake. If his DMC-12 sports cars roll off the assembly line–and if they sell–he will have been avenged. He will have shown the bastards that they were wrong, goddammit, that General Motors was wrong about him and what you can do with an auto company. He will have shown that you can make a virtually rustproof car with a stainless steel skin and underbody, with air bags, with a reinforced plastic frame–a car that won’t kill you in a sixty-mile-an-hour, head-on crash, a car that can last twenty-five years or more. And he will have shown that you can sell that car, even at about $14,000 a copy. And if the platoons of pinstriped, cordovan-shod executives of GM doubt it, they can go and stick their noses up its tail pipe.”

••••••••••

John DeLorean speaks at the DeLorean Car Show in Cleveland in 2000:

Another John DeLorean post:

Tags: John DeLorean, William Flanagan

From Bell Labs.

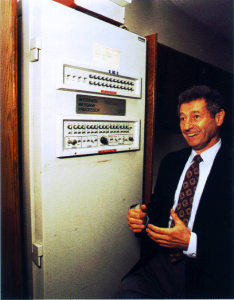

The first host-to-host message sent over the nascent Internet occurred in 1969 at UCLA, which has belatedly created a shrine to the place where it all started. An excerpt from a story on the topic by Southern California Public Radio:

“In a small computer lab in a forgotten building at UCLA, Professor Leonard Kleinrock and a group of graduate students sent the very first message over what would become the Internet, back in 1969. Since that milestone, the room was in continuous use as a classroom, and its significance to history was all but forgotten. But now the room has been transformed into a re-creation of the ARPA lab, complete with the original equipment from the ’60s and period furnishings to match.

The Interface Message Processor, or IMP as engineers fondly call it, stands in the same spot in 3420 Boelter Hall today as it did in 1969. It functioned much like a modem, sending messages from the host computer, an SDS Sigma 7, through the network to an IMP in a remote location, which relayed it to another host computer.

During the ’60s, UCLA was chosen as the first node of what was known as ARPANET, a precursor to the Internet funded by the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA). UCLA set up the very first network connection between their IMP and the IMP at Stanford Research Institute in northern California.

On October 29, 1969, Kleinrock and his team undertook a simple task to test the network – sending a login request from their host computer to the host computer at SRI.”

••••••••••

Leonard Kleinrock recalls the birth of the Internet:

Tags: Leonard Kleinrock

Ever-cheerful playwright Tennessee Williams talks to Bill Boggs. Full Q&A here.

Tags: Bill Boggs, Tennessee Williams

Video short about the Venus Project.

Another Jacque Fresco post:

Tags: Jaques Fresco

It was on the brink for a long time. (Thanks Dangerous Minds.)

It’s difficult to fathom what would have become of the career of schlockmeister Roger Corman if The Intruder, his incendiary 1962 melodrama about race baiting during the tense moments of the Civil Rights Movement, hadn’t been such an unreleasable flop. Rather than failing because of incompetence, the movie never made its mark because it was too searing a statement about too raw a subject, its dialogue too frank to easily take.

Adam Cramer (William Shatner) describes himself as a social worker, but he’s really an antisocial one. The Elmer Gantry of racial divisiveness, the white-suited Cramer storms into a small Southern town on the eve of court-ordered school integration and quickly puts his oratory skills to work. The locals spit more racial epithets than they do tobacco juice, but they’ve become resigned to the change in the air even if they don’t like it. But Cramer senses that there’s rabble to be roused, and his passionate pleas soon have the townsfolk in a lather.

Even the most liberal person in the community, the newspaper editor Tom McDaniel (Frank Maxwell), was against the forced integration, but after a black church is burned to the ground, he has a change of heart. But the interloper quickly has the scribe outnumbered and McDaniel and the black students reporting for class at white schools may be in grave danger.

Despite some writerly plot twists, Corman’s feel for the material and Shatner’s scary intensity make this picture one of the finer B-movies you’ll ever see. But it was a one-and-done reach for greatness by the director. When The Intruder proved too tough a sell, Corman resigned to be satisfied as an entertainer who buried anything meaningful very deep in the subtext. The material he worked with was never so rich again, and his sharp eye for composition on display here grew fuzzier as the screenplays grew worse. Of course, if he hadn’t turned to profitable dreck, Corman likely wouldn’t have been in a position to have midwifed filmmaking careers for Scorsese, Coppola and Bogdanovich, among others. But no matter what is and what might have been, The Intruder remains a testament to Corman’s early abilities.• (The Intruder just became available for streaming on Netflix.)

••••••••••

Recent Film Posts:

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: They Came Back (2004)

- Classic Film: The Rapture (1991)

- Recent Film: Somewhere

- Recent Film: Another Year

- Classic Film: The Truman Show (1996)

- Classic Film: Salesman (1968)

- Classic Film: Night of the Living Dead (1968)

- Classic Film: The Conversation (1974)

- Classic Film: King of Comedy (1982)

- Recent Film: Dogtooth

- Classic Film: RoboCop (1987)

- Recent Film: Marwencol (2010)

- Classic Film: Being There (1979)

- Classic Film: Woman in the Dunes (1964)

- Classic Film: The Man in the White Suit (1951)

Tags: Frank Maxwell, Roger Corman, William Shatner

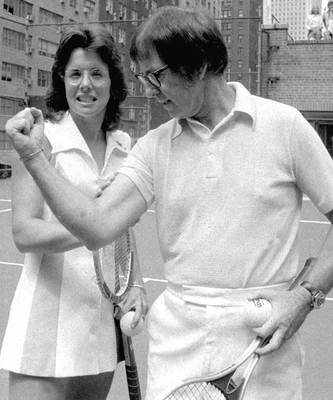

Bobby Riggs, that huckster, profiled by Mike Wallace in 1973 for 60 Minutes prior to facing Billie Jean King in the Battle of the Sexes.

King and Riggs shill together for Sunbeam’s Mist-Stick Curler Dryer:

Tags: Bille Jean King, Bobby Riggs, Mike Wallace

Old-school NASA.

More Space Exploration posts:

In a 1993 Wired interview conducted by Gary Wolf, Steve Jobs, who was then doing his walkabout at NeXT, spoke cautiously about the World Wide Web. He thought it would be great for commerce but maybe not landscape-altering in essential ways. He was right in that all the connectivity and information hasn’t stopped wars or thinned the ranks of ignorant politicians.

One interesting thing that Jobs said was that the Web wouldn’t have the same awesome immediate impact that radio and TV had, that it would creep up on people. I think that’s true. Because the Web is controlled to a good extent by users, its wow factor is revealed incrementally, as people continue to tinker with it and grow it out. Ultimately, it will have much greater consequence for change than earlier technologies that made a bigger initial splash but were hampered by central control. An excerpt from the Q&A:

“What’s the biggest surprise this technology will deliver?

Steve Jobs: The problem is I’m older now, I’m 40 years old, and this stuff doesn’t change the world. It really doesn’t.

That’s going to break people’s hearts.

Steve Jobs: I’m sorry, it’s true. Having children really changes your view on these things. We’re born, we live for a brief instant, and we die. It’s been happening for a long time. Technology is not changing it much – if at all.

These technologies can make life easier, can let us touch people we might not otherwise. You may have a child with a birth defect and be able to get in touch with other parents and support groups, get medical information, the latest experimental drugs. These things can profoundly influence life. I’m not downplaying that. But it’s a disservice to constantly put things in this radical new light – that it’s going to change everything. Things don’t have to change the world to be important.

The Web is going to be very important. Is it going to be a life-changing event for millions of people? No. I mean, maybe. But it’s not an assured Yes at this point. And it’ll probably creep up on people.

It’s certainly not going to be like the first time somebody saw a television. It’s certainly not going to be as profound as when someone in Nebraska first heard a radio broadcast. It’s not going to be that profound.

Then how will the Web impact our society?

Steve Jobs: We live in an information economy, but I don’t believe we live in an information society. People are thinking less than they used to. It’s primarily because of television. People are reading less and they’re certainly thinking less. So, I don’t see most people using the Web to get more information. We’re already in information overload. No matter how much information the Web can dish out, most people get far more information than they can assimilate anyway.”

••••••••••

The William Morris Agency gets NeXT computers in 1990:

From Japan, of course.

Italian novelist Paolo Giordano went to Disneyland all by his lonesome and filed a report for the Wall Street Journal. An excerpt:

Italian novelist Paolo Giordano went to Disneyland all by his lonesome and filed a report for the Wall Street Journal. An excerpt:

“I take no rides in Disneyland, not even one, but I go into the reassuring auditorium where they show the return of ‘Captain EO’ in amazing 3-D and the temperature change is severe. Mothers extract sweaters from their bags, but the children have no intention of wearing them. They are thinking how funny they look with those big 3-D glasses on their faces, even though 3-D is no innovation for them; it’s nothing special, like this place Disneyland is nothing special. It looks a little old and there’s much more future in the Nintendo DSs, iPods, PlayStation Portables they’re carrying in their pockets.

Only small children still marvel—the Asian girl sitting at my left side, for example, she’s terrified by the dark and the wild assault of people trying to get the best seats and by Captain EO himself who—I’m discovering now—is Michael Jackson, close to his original color and surrounded by a group of tiny farting monsters. He has a mission to accomplish that later results in him dancing amid androids and repeating ‘We are here to change the world,’ which more or less is what he’d said throughout his career. When the seats start bouncing to the beat of the bass drum, I think that one of the ways Michael Jackson changed the world was to build a place similar to this one, a colorful trap for children where he decided to live, and the reason why he did it appears to me at once to be clear, tender, dreadful and incomprehensible.”

••••••••••

A little Captain EO:

Other Disney-related posts:

Tags: Paolo Giordano

I don’t know why, but I would rather read newspapers and magazines online but still prefer to read old-fashioned, non-virtual books. Maybe it has to do with the length of time we spend with an article as opposed to a longer work. I think it’s something I’ll get over soon, though I probably won’t have a choice. But I’m all in favor of digitization of printed materials of value (and even of dubious value) and the democratization of scholarship that it allows. James Gleick speaks to this issue a new Op-Ed piece in the New York Times. An excerpt:

“Where some see enrichment, others see impoverishment. Tristram Hunt, an English historian and member of Parliament, complained in The Observer this month that ‘techno-enthusiasm’ threatens to cheapen scholarship. ‘When everything is downloadable, the mystery of history can be lost,’ he wrote. ‘It is only with MS in hand that the real meaning of the text becomes apparent: its rhythms and cadences, the relationship of image to word, the passion of the argument or cold logic of the case.’

I’m not buying this. I think it’s sentimentalism, and even fetishization. It’s related to the fancy that what one loves about books is the grain of paper and the scent of glue.

Some of the qualms about digital research reflect a feeling that anything obtained too easily loses its value. What we work for, we better appreciate. If an amateur can be beamed to the top of Mount Everest, will the view be as magnificent as for someone who has accomplished the climb? Maybe not, because magnificence is subjective. But it’s the same view.”

Another James Gleick post:

Tags: James Gleick

In the future, you will be able to live forever. Though videos about immortality will still, apparently, have shitty production values.

Suitcase-sized cell phones.

I blogged recently about an excellent thumbnail description of Ben Katchor’s artistic heritage which ran on the Los Angeles Review of Books site, and that same site just published the first part of “The Ghost of Wrath,” a revisionist nine-part series about eminent (and hated) Angeleno Harrison Gray Otis that was written by Mike Davis. Otis is the original force behind the Los Angeles Times, and one of the chief “inventors” of modern L.A. The first few paragraphs:

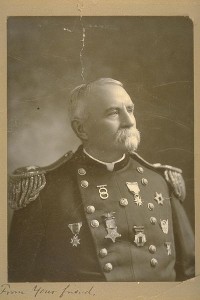

“General Harrison Gray Otis is the wrathful gargoyle with a walrus moustache and Custer goatee who glowers down on us from the battlements of Los Angeles’s Open Shop era. The proprietor of Times-Mirror Company from 1882 to 1917, he was recently hailed in a PBS documentary as the ‘inventor’ of modern Los Angeles, both as an individual and via his descendants, the Chandler family.

Yet his eminence in the city’s history is cast almost entirely as shadow. Five or six serious books have been written about the Los Angeles Times and the Chandlers, but there is no published biography of the dynasty’s founder and leviathan. This is a major missing thread in the narrative tapestry of the current renaissance of Los Angeles history, but given the archival and literary obstacles in any potential biographer’s path, it is not surprising.

First, no one has yet excavated the pharaoh’s tomb. Rumors abound, especially in the tearoom of the Huntington Library, about family archives kept in a San Marino vault. But it is also possible that son-in-law and successor, Harry Chandler, destroyed many of Otis’s private papers when he ordered his own files burned after his heart attack in 1944. (Chandler might have been reacting to the literary and cinematic assaults on fellow-publisher and chief competitor, William Randolph Hearst.)

Second, any biographer has to tackle the fact that Otis was probably the most hated man in Ragtime America. His enemies ecumenically spanned a spectrum from evangelists to citrus growers, socialists to robber barons. Although chiefly remembered for his relentless crusade to destroy the labor movement in Los Angeles, Otis waxed most savage in his attacks on reformers within his own Republican Party. Progressive Republicans, in turn, repaid his vitriol with eloquent interest.”

Tags: Harrison Gray Otis, Mike Davis

In Cloquet, Minnesota. (Thanks Open Culture.)

Tags: Frank Lloyd Wright

The amazing Hiroshi Teshigahara and a band of peers collaborated on this stylized 24-minute documentary, “Tokyo 1958.” No English subtitles, but the visuals and score easily carry it.

"They viewed humans as essentially good, influenced by rational deliberation, and tending towards co-operation."

From Evgeny Morozov’s concise history of the Internet at Prospect:

“But studying the history of the internet is impossible without studying the ideas, biases, and desires of its early cheerleaders, a group distinct from the engineers. This included Stewart Brand, Kevin Kelly, John Perry Barlow, and the crowd that coalesced around Wired magazine after its launch in 1993. They were male, California-based, and had fond memories of the tumultuous hedonism of the 1960s.

These men emphasised the importance of community and shared experiences; they viewed humans as essentially good, influenced by rational deliberation, and tending towards co-operation. Anti-Hobbesian at heart, they viewed the state and its institutions as an obstacle to be overcome—and what better way to transcend them than via cyberspace? Their values had profound effects on the mechanics of the internet, not all of them positive. The proliferation of spam and cybercrime is, in part, the consequence of their failure to predict what might happen as a result of the internet’s open infrastructure. The first spam message dates back to 1978; now, 85 per cent of all email traffic in the world is spam.

Perhaps the cheerleaders’ greatest achievement was in wresting dominance of the internet from the founding engineers, whose mentality was that of the Cold War. These researchers greatly depended on the largesse of the US department of defence and its nervous anticipation of a nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union. The idea of the ‘virtual community’—the antithesis of Cold War paranoia—was popularised by the writer and thinker Howard Rheingold. The term arose from his experiences with Well.com, an early precursor to Facebook.”

•••••••••

Evgeny Morozov argues that the Internet strenghtens dictatorial regimes, in his contrarian TED Talk:

Tags: Evgeny Morozov

Occasional smoker Tom Snyder talks to Durk Pearson and Jerry Pournelle about media changes on the horizon, including the death of newsprint.

Tags: Durk Pearson, Jerry Pournelle, Tom Snyder

Ooh, Talkies! My favorite kind of pictures, apart from Weepies.

A 1981 interview with famed street photographer Garry Winogrand.

Winogrand’s shooting style, as recalled by a former student: “We quickly learned Winogrand’s technique–he walked slowly or stood in the middle of pedestrian traffic as people went by. He shot prolifically. I watched him walk a short block and shoot an entire roll without breaking stride. As he reloaded, I asked him if he felt bad about missing pictures when he reloaded. ‘No,’ he replied, ‘there are no pictures when I reload.’ He was constantly looking around, and often would see a situation on the other side of a busy intersection. Ignoring traffic, he would run across the street to get the picture.

Incredibly, people didn’t react when he photographed them. It surprised me because Winogrand made no effort to hide the fact that he was standing in way, taking their pictures. Very few really noticed; no one seemed annoyed. Winogrand was caught up with the energy of his subjects, and was constantly smiling or nodding at people as he shot. It was as if his camera was secondary and his main purpose was to communicate and make quick but personal contact with people as they walked by.”

Tags: Garry Winogrand