In the wake of the 2008 economic collapse, austerity felt to many the right thing to do: We needed to punish ourselves. But that policy was moralistic and incorrect, since what we actually needed was to borrow and spend. Is our view of labor also driven by a misplaced sense of morality? Brian Dean asks this question and others in “Antiwork,” a Contributoria essay which reconsiders the meaning of toil. An excerpt:

“Work” is seen as a virtue, but it covers the moral spectrum from charity and art to forced labour and banking. Belief in the inherent moral good of work has been used historically in social engineering, notably during the shift from agriculture to industry, when the Protestant work ethic was used to motivate workers and to justify punishment, including whipping and imprisonment of “idlers”. (In The Making of the English Working Class, historian EP Thompson describes how the ethos of Protestant sects such as Methodism effectively provided the prototype of the disciplined, punctual worker required by the factory owners.)

Work’s assumed virtue has always been about more than its utility or market value. George Lakoff, the cognitive linguist, provided a clue in the frame of “work as obedience.” The first virtue we learn as children is obeying our parents, particularly in performing tasks we don’t enjoy. Later, as adults, we’re paid to obey our employers – it’s called work. Work and virtue are thus connected in our neurology in terms of obedience to authority. That’s not the only cognitive frame we have for the virtue of work, but it’s the one that is constantly reinforced by what Lakoff calls the “strict father” conservative moral system.

This “strictness” moral framing is implicit, for example, in the current welfare system. An increasingly punitive approach is adopted towards those who don’t follow the prescribed “job-seeking” regimen – a trend that most political parties seem to approve of. Politicians boast of getting “tough on dependency culture”, and when they talk of “clamping down” on the “hardcore unemployed”, you’d think they were referring to criminals.

Emphasis on punishment is the sign of an obedience frame. Work itself has a long history as punishment for disobedience, as the Book of Genesis illustrates – Adam and Eve had no work until they disobeyed God, who imposed it as their punishment: “Cursed is the ground because of you; in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life.” Unpaid work, or “community service,” is still sometimes dictated as punishment by courts. Workfare programmes similarly involve mandatory work without wages – it looks very much like punishment for the “sin” of unemployment.

Workfare illustrates a difference between framing and spin. The cognitive frame is paternalistic, morally strict, punishment-based (much like “community service”), while the political spin is all about “helping” people “integrate” back into society. Genuine help, of course, shouldn’t require the threat of losing what little income one has.

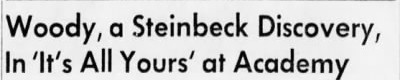

Morally, it seems that politicians, most of the media and a large section of the public are still stuck in the Puritan codes and scripts that, following the Reformation and into the industrial revolution, dominated social attitudes to work and idleness in England, America and much of Europe.•