Do most survivalists fear the end is near or that it will never arrive?

The preppers are ready for any calamity, to such an extent that it would almost be a shame if they didn’t get to break out their Bug Out Bags. Some almost seem to be welcoming of the end, whatever that would entail, weary of the modern madness. I mean, you don’t dress for a party you don’t want to attend. You certainly can’t say this about all involved, but there are those with a taste for freeze-dried food that no other meal will satisfy.

And because whatever age your living in is the modern one, such concerns are nothing new. From a 1981 People piece about the second boom in the American bomb-shelter business:

They call themselves survivalists. They would have us believe we are on the brink of nuclear war, economic collapse, technological breakdown, Communist takeover—you name it. In a mushrooming movement that recalls the bomb shelter craze of the 1950s, these end-is-near believers, thought to number somewhere between two and five million and concentrated in the Western U.S., are busy storing food, weapons and gasoline in remote hideaways against the day of reckoning. It may seem unduly pessimistic of them—or optimistic, given their plain belief in living through the apocalypse. But whatever the merits of their reasoning, they are a peculiarly American group, styling themselves as rough-and-ready pioneers on the most discouraging frontier of all. “Most individuals in societies fearing collapse band together,” observes Dr. Alan Dundes, professor of anthropology at Berkeley. “But Americans take to the hills to fend off nuclear holocaust with a shotgun and a supply of food.”

And, of course, there’s gold in them hills, as enterprising businessmen, real estate developers, authors and teachers of self-defense have been quick to discover. Fallout shelters are being dug by the thousands, and freeze-dried food sales (including a line of nonperishable high-protein dog food called Sir Vival) are heating up. Many of the original survivalists were Mormons, descendants of ruggedly self-sufficient pioneers whose church has historically called upon every head of a household to store enough food for his family to last a year. The recent trend, though, is closely linked to current events: the Arab oil embargo, inflation, the Iranian hostage crisis. Each has translated as an uptick in the survival business.

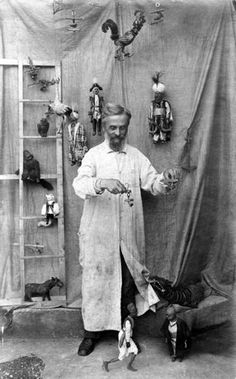

On these pages are three men who have been caught up in the doom boom: an author, a fallout-condo builder and a retailer of survival goods, Bill Pier—one of a growing number of capitalists who have a stake in selling the future short. “Survival is the last thing we have,” says Pier. “It’s always been there. And we have a tendency to rise to the occasion or we wouldn’t be here, would we?”

Doug Clayton’s dad sees a craven new world

Little Dougie Clayton, now nearly 2, has a very special birthright: The family’s fallout shelter doubles as his romper room. Dougie’s father, Bruce, like many other Californians, believes that Armageddon is right around the corner, and besides the fallout shelter, there are a year’s supply of food, medical supplies in the pantry and two water beds full of pure drinking water in the bedrooms. “Survivalism is the ultimate vote of no confidence in the government,” says Clayton, 31. “If disaster comes, survivalists will help themselves. They are not hostile, just contemptuous.”

Clayton’s contempt was informed by his studies for a Ph.D. in ecology at the University of Montana. Curious about the possible effect of a nuclear attack, he came across what he considered horrifyingly simplistic and sometimes incorrect civil defense information provided by the government. After five years of research, he published Life after Doomsday: A Survivalist Guide to Nuclear War and Other Major Disasters (Paladin Enterprises, $19.95) early last year. He is currently working on a sequel, a guide to subsisting on wild edibles.

Clayton is less concerned about living through the holocaust than he is about peaceful coexistence with fellow survivors. “Some of them will have no food but thousands of dollars’ worth of guns and ammunition,” he says. “You ask them how they intend to get food in an emergency and they say right to your face, ‘We figure we’ll take yours.’ ” To guard against this possibility, Clayton is armed with military assault rifles and police riot guns and is ready to pack his family off to a secret retreat in the Sierra foothills. “I was never very sure that I could actually shoot people just to save myself,” he says, “but after Dougie was born, I discovered there was no question in my mind I would shoot to protect him.”•