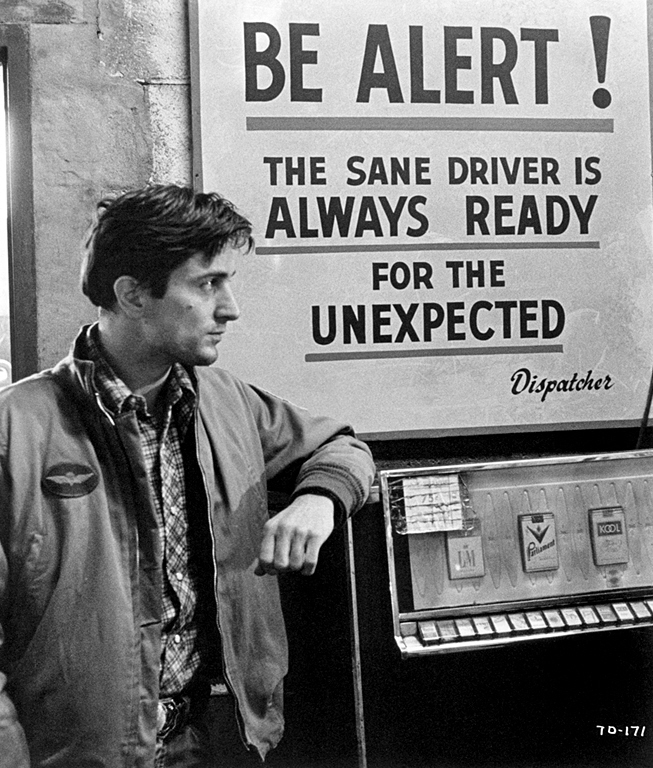

At any moment in history we accept some things that are wrong and others that are even monstrous. But which ones are those in our current age, a time when technology is viewed as totem?

In “Humanist Among the Machines,” an Aeon essay by Ian Beacock, the writer suggests we seek alternatives to the received wisdom of the Digital Age by taking a cue from twentieth-century historian Arnold Toynbee, who pushed back at the “mechanization” of Homo sapiens and its world in an earlier period.

In one passage, Beacock writes that “As Toynbee recognised, scientific principles and technical innovations might help us build a better railway, a faster locomotive – but they aren’t very good at telling us who can buy tickets, what direction we should lay the track, or whether we should be taking the train at all.” The thing is, technology has gotten pretty good at telling us those type of things and is getting better all the time. Of course, that’s just more reason to pay heed to Beacock’s clarion call. As tech’s influence casts a larger shadow, the light we shine on it should be brighter still.

An excerpt:

There’s no shortage of writing about Silicon Valley, no lack of commentary about how smartphones and algorithms are remaking our lives. The splashiest salvos have come from distinguished humanists. In The New York Times Book Review, Leon Wieseltier, acidly indicted the culture of technology for flattening the capacious human subject into a few lines of computer code. Rebecca Solnit, in the London Review of Books, rejects the digital life as one of distraction, while angrily documenting the destruction of bohemian San Francisco at the hands of hoodied young software engineers who ride to work aboard luxury buses like “alien overlords.” Certainly there’s reason to be outraged: much good is being lost in our rush to optimisation. Yet it’s hard not to think that we’ve been so distracted by such totems as the Google Bus that we’re failing to ask the most interesting, constructive, radical questions about our digital times. Technology isn’t going anywhere. The real issue is what to do with it.

Scientific principles and the tools they generate aren’t necessarily liberating. They’re not inherently destructive, either. What matters is how they’re put to use, for which values and in whose interest they’re pressed into service. Silicon Valley’s most successful companies often present their services as value-free: Google just wants to make the world’s information transparent and accessible; Facebook humbly offers us greater connectivity with the people we care about; Lyft and Airbnb extol the virtues of sharing among friends, new and old. If there are values here, they seem to be fairly innocuous ones. How could you possibly oppose making new friends or learning new things?

Yet each of these high-tech services is motivated by a vision of the world as it ought to be, an influential set of assumptions about how we should live together, what we owe one another as neighbours and citizens, the relationship between community and individual, the boundary between public good and private interest. Technology comes, in other words, with political baggage. We need critics who can pull back the curtain, who can scrutinise digital technology without either antipathy or boosterism, who can imagine how it might be used differently. We need critics who can ask questions of value.•