It’s different now that everything is a smartphone, but sometimes I’ll hear an older ringtone in an office or somewhere, and it stops me for a second because it’s similar to the one used on Homicide: Life on the Street, the great show David Simon’s journalism birthed. That was a sound that couldn’t possibly bring good news, a Greek chorus as an electric current, reminding anyone within earshot of the human churn rate. That show–and other Simon shows–stay with me even though I’m not someone who watches much television. I actually haven’t had a set in years.

It’s just so jarring to see the kind of people I grew up around, if in Queens, not Baltimore, on TV. I still sometimes think of the Homicide episode which opened with two dysfunctional middle-aged brothers being arrested for hiding their mother’s corpse so that they could keep collecting her Social Security checks, so left behind by society they were, so unable to fend for themselves in a modern world. Those characters make me recall the real characters who lived in the same building in Astoria as my family when I was a kid: People who didn’t quite fit into the scheme of things and accepted the margins, though there wasn’t much choice. They didn’t live as much as they eked. Those smartphones, with their customized ringtones, have the potential to deliver people from the margins, or they might move more people there. Time will tell.

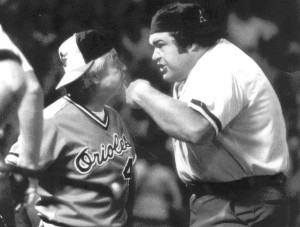

Never have gotten to read Simon’s Baltimore Sun reportage, but whenever I see a piece of prose he writes here or there, he seems, in print, the hard-boiled philosopher, which is no surprise. Like someone who’s done the math, who knows the daunting numbers all too well, but still believes they can add up-or the equation can be changed. In a new Sports Illustrated piece, Simon opines on the playoff chances of his beloved Orioles. An excerpt:

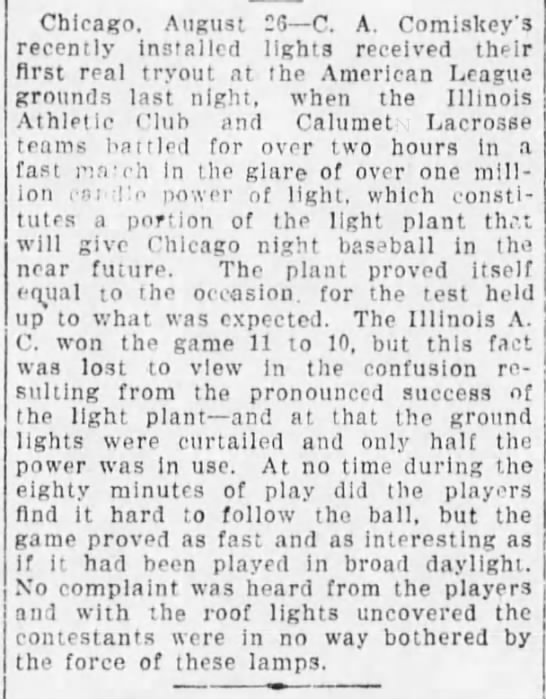

“Anything that can happen, will. And in an infinite universe, it will happen repeatedly. The full implications of the second law of thermodynamics apply to the American League East just as soundly as to a million monkeys at a million typewriters. Eventually, and regardless of all prior history, the Baltimore Orioles are going to type the complete works of Shakespeare.

How do we know this?

Well, for one thing, there is no God. There is only science. If there were a God, he would be—as evidenced by all of modern baseball history—a devoted fan of the Yankees. And God, at least the Judeo-Christian version of Him rather than the Aristotelian unmoved mover, is said to be good. Ergo, there is no God.

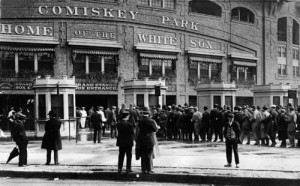

So, alone in this cold and expanding universe, we are left to consider the random motion of atoms, of protons and electrons and quarks, as these elemental essences dance and glance their way through the hollow space of, say, a Camden Yards, a Fenway, a Yankee Stadium. There is no romance to the matter, no theology, no purposed narrative even—if by narrative you mean a tale with a moral, with cause and effect, fate or redemption, hubris or vindication. No one is making a point here; the monkeys just keep typing.

Entering play on Thursday, the Orioles were 10 games over .500, three up on a Toronto team that was dominant a month ago and also three ahead of a battered, shield-down Yankees Death Star. The O’s run differential is +24—encouraging news indeed when you consider that the oh-why-the-hell-not O’s of two years ago, the ones who won 93, were only +7 as they stole every one-run and extra-inning game.

The current Orioles, sitting pretty atop the once-vaunted AL East, are actually more legitimate in some ways than the 2012 team that went to the playoffs for the first time since Clinton was president, Lewinsky was a name known but to him, and the world was still debating whether all electronics would cease to operate properly at the stroke of the millennium.

In other words, all I am saying is give Pearce a chance. We can win this.

Why? Because the Yankees’ rotation is shredded and their lineup ordinary, and because Tanaka couldn’t pitch every game and now may not be able to pitch at all. Because Toronto’s batting order—topped with speed and stacked with power—is now hollowed by injury, so much so that talk of trading only for a front-line starter now yields to talk of trading for some of everything. Because Boston is as flat as Shane Victorino on the trainer’s table, awaiting another epidural. And the Rays? Where did those guys go?

The electrons dance away from the great as well as the good. Overall, this is no comfort whatsoever; to accept probability theory is to acknowledge that eventually the United States and the Russians must engage in a nuclear exchange or that your goodly wife will eventually screw the mailman or the yoga instructor. But it also means the American League East can’t forever be the home of predominance.

All right, you say, maybe Baltimore can win the division. Maybe Jimenez gets off the DL and reels off a half-dozen wins. Maybe Davis finds his stroke. Maybe the monkeys can produce a Cymbeline or a Titus Andronicus.

But for Hamlet or Lear, you’re thinking I’m going to need more simians and more keyboards. In the AL Central, Detroit is running away and showing no holes. And the Athletics are throwing up gaudy numbers. Here you sit, Simon, hermetically sealed in your 12-foot-wide South Baltimore row house, nattering on about the Orioles’ run differential? Really? The A’s have scored 163 runs more than their opponents—better than a run and a half more in every game. That’s a statistic that doesn’t smell of probability theory but stinks of certitude.

To which, I reply by discarding stats entirely. To hell with Billy Beane. Chew instead on more quantum mechanics—the uncertainty principle of which clearly states that any effort to measure quantities is disturbed by the very act of observation. In other words Heisenberg has Bill James by the ass.

Remember: Anything that can happen in an infinite and expanding universe eventually will. And despite some long years wandering amid the deep-space weight of baseball dark matter, Baltimore has now crawled from its black hole.”