Thomas E. Ricks of Foreign Policy asked one of the most horrifying questions about America you can pose: Will we have another civil war in the next ten to fifteen years? Keith Mines of the United States Institute of Peace and a career foreign service officer provided a sobering reply, estimating the chance for large-scale internecine violence at 60%.

Things can change unexpectedly, sometimes for the better, but it sure does feel like we’re headed down a road to ruin, with the anti-democratic, incompetent Trump and company provoking us to a tipping point. The Simon Cowell-ish strongman may seem a fluke because of his sizable loss in the popular vote, but in many ways his political ascent is the culmination of the past four decades of dubious U.S. cultural, civic, economic, technological and political decisions. We’re not here by accident.

· · ·

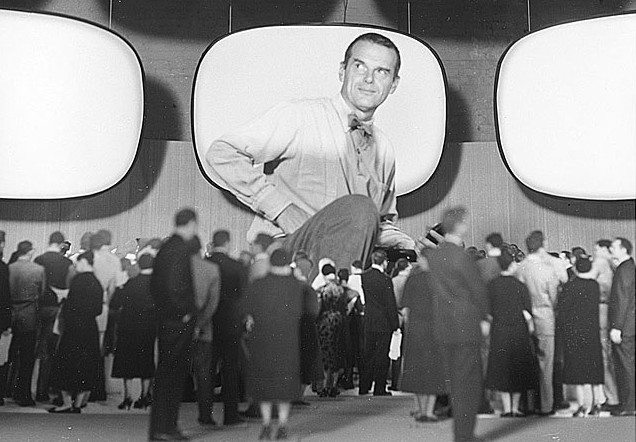

One of the criteria on which Mines bases his diagnosis: “Press and information flow is more and more deliberately divisive, and its increasingly easy to put out bad info and incitement.” That triggered in me a memory of a 2012 internal Facebook study, which, unsurprisingly, found that Facebook was an enemy of the echo chamber rather than one of its chief enablers. I’m not saying the scholars involved were purposely deceitful, but I don’t think even Mark Zuckerberg would stand by those results five years later. We’re worlds apart in America, and social media, and the widespread decentralization of all media, has hastened and heightened those divisions.

· · ·

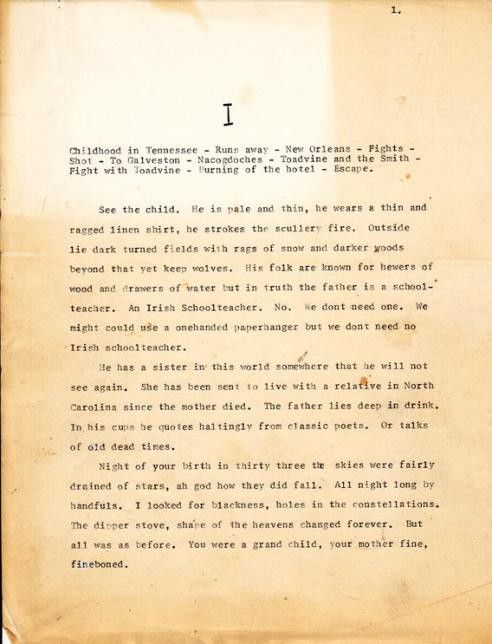

An excerpt from Farhad Manjoo’s 2012 Slate piece “The End of the Echo Chamber,” about the supposed salubrious effects of social networks, is followed by Mines’ opening.

From Manjoo:

Today, Facebook is publishing a study that disproves some hoary conventional wisdom about the Web. According to this new research, the online echo chamber doesn’t exist.

This is of particular interest to me. In 2008, I wrote True Enough, a book that argued that digital technology is splitting society into discrete, ideologically like-minded tribes that read, watch, or listen only to news that confirms their own beliefs. I’m not the only one who’s worried about this. Eli Pariser, the former executive director of MoveOn.org, argued in his recent book The Filter Bubble that Web personalization algorithms like Facebook’s News Feed force us to consume a dangerously narrow range of news. The echo chamber was also central to Cass Sunstein’s thesis, in his book Republic.com, that the Web may be incompatible with democracy itself. If we’re all just echoing our friends’ ideas about the world, is society doomed to become ever more polarized and solipsistic?

It turns out we’re not doomed. The new Facebook study is one of the largest and most rigorous investigations into how people receive and react to news. It was led by Eytan Bakshy, who began the work in 2010 when he was finishing his Ph.D. in information studies at the University of Michigan. He is now a researcher on Facebook’s data team, which conducts academic-type studies into how users behave on the teeming network.

Bakshy’s study involves a simple experiment. Normally, when one of your friends shares a link on Facebook, the site uses an algorithm known as EdgeRank to determine whether or not the link is displayed in your feed. In Bakshy’s experiment, conducted over seven weeks in the late summer of 2010, a small fraction of such shared links were randomly censored—that is, if a friend shared a link that EdgeRank determined you should see, it was sometimes not displayed in your feed. Randomly blocking links allowed Bakshy to create two different populations on Facebook. In one group, someone would see a link posted by a friend and decide to either share or ignore it. People in the second group would not receive the link—but if they’d seen it somewhere else beyond Facebook, these people might decide to share that same link of their own accord.

By comparing the two groups, Bakshy could answer some important questions about how we navigate news online. Are people more likely to share information because their friends pass it along? And if we are more likely to share stories we see others post, what kinds of friends get us to reshare more often—close friends, or people we don’t interact with very often? Finally, the experiment allowed Bakshy to see how “novel information”—that is, information that you wouldn’t have shared if you hadn’t seen it on Facebook—travels through the network. This is important to our understanding of echo chambers. If an algorithm like EdgeRank favors information that you’d have seen anyway, it would make Facebook an echo chamber of your own beliefs. But if EdgeRank pushes novel information through the network, Facebook becomes a beneficial source of news rather than just a reflection of your own small world.

That’s exactly what Bakshy found. His paper is heavy on math and network theory, but here’s a short summary of his results. First, he found that the closer you are with a friend on Facebook—the more times you comment on one another’s posts, the more times you appear in photos together, etc.—the greater your likelihood of sharing that person’s links. At first blush, that sounds like a confirmation of the echo chamber: We’re more likely to echo our closest friends.

But here’s Bakshy’s most crucial finding: Although we’re more likely to share information from our close friends, we still share stuff from our weak ties—and the links from those weak ties are the most novel links on the network. Those links from our weak ties, that is, are most likely to point to information that you would not have shared if you hadn’t seen it on Facebook.•

From Mines:

What a great but disturbing question (the fact that you can even ask it). Weird question for me as for most of my career I have been traveling the world observing other countries in various states of dysfunction and answering this same question. In this case if the standard is largescale violence that requires the National Guard to deal with in the timeline you lay out, I would say about 60 percent.

I base that on the following factors:

— Entrenched national polarization of our citizenry with no obvious meeting place. (Not true locally, however, which could be our salvation; but the national issues are pretty fierce and will only get worse).

— Press and information flow is more and more deliberately divisive, and its increasingly easy to put out bad info and incitement.

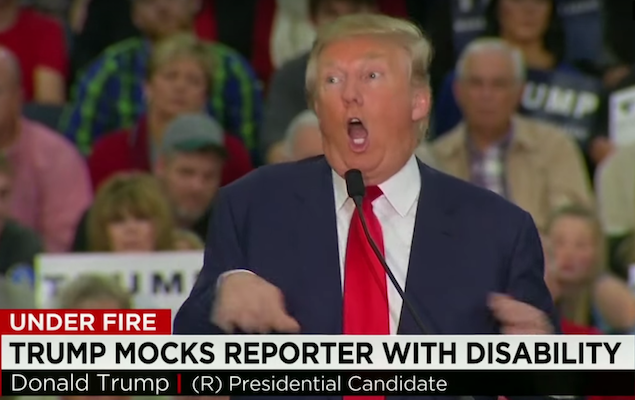

— Violence is “in” as a method to solve disputes and get one’s way. The president modeled violence as a way to advance politically and validated bullying during and after the campaign. Judging from recent events the left is now fully on board with this, although it has been going on for several years with them as well — consider the university events where professors or speakers are shouted down and harassed, the physically aggressive anti-Israeli events, and the anarchists during globalization events. It is like 1859, everyone is mad about something and everyone has a gun.

— Weak institutions — press and judiciary, that are being further weakened. (Still fairly strong and many of my colleagues believe they will survive, but you can do a lot of damage in four years, and your timeline gives them even more time).

— Total sellout of the Republican leadership, validating and in some cases supporting all of the above.•