When Norman Mailer was assigned to write of the Apollo 11 mission, he covered it as a prizefight that had been decided in the staredown, knowing that despite the outcome of this particular flight, the Eagle had already landed, technology had eclipsed humans in many ways, and our place in the world was to be recalibrated. Since then, we’ve constantly redefined why we exist.

In the 2003 essay “Just Who Will Be We, in 2493?” Douglas Hofstadter argued we needn’t necessarily fear silicon-based creatures crowding us at the top. Perhaps, he thought, we should be welcoming, like natives embracing immigrants. An excerpt:

If we shift our attention from the flashy but inflexible kinds of game-playing programs like Deep Blue to the less glamorous but more humanlike programs that model analogy-making, learning, memory, and so forth, being developed by cognitive scientists around the world, we might ask, “Will this kind of program ever approach a human level of intelligence?” I frankly do not know. Certainly it’s not just around the corner. But I see no reason why, in principle, humanlike thought, consciousness, and emotionality could not be the outcome of very complex processes taking place in a chemical substrate different from the one that happens, for historical reasons, to underlie our species.

The question then arises – a very hypothetical one, to be sure, but an interesting one to ponder: When these “creatures” (why not use that term?) come into existence, will they be threats to our own species? My answer is, it all depends. What it depends on, for me, comes down to one word: benevolence. If robot/ computers someday roam along with us across the surface of our planet, and if they compose music and write poetry and come up with droll jokes- and if they leave us pretty much alone, or even help us achieve our goals- then why should we feel threatened? Obviously, if they start trying to push us out of our houses or to enslave us, that’s another matter and we should feel threatened and should fight back.

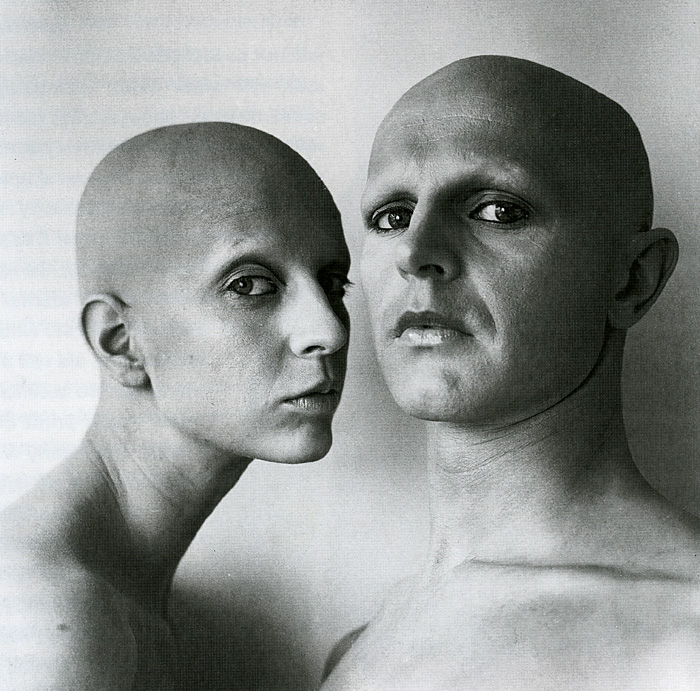

But just suppose that we somehow managed to produce a friendly breed of silicon-based robots that shared much of our language and culture, although with differences, of course. There would naturally be a kind of rivalry between our different types, perhaps like that between different nations or races or sexes. But when the chips were down, when push came to shove, with whom would we feel allegiance? What, indeed, would the word “we” actually mean?

There is an old joke about the Lone Ranger and his sidekick Tonto one day finding themselves surrounded by a shrieking and whooping band of Indians circling in on them with tomahawks held high. The Lone Ranger turns to his faithful pal and says, “Looks like we’re done for, Tonto … ” To which Tonto replies, “What do you mean, we, white man?”

Let me suggest a curious scenario. Suppose we and our artificial progeny had coexisted for a while on our common globe, when one day some weird strain of microbes arose out of the blue, attacking carbon-based life with a viciousness that made today’s Ebola virus and the old days’ Black Plague seem like long-lost friends. After but a few months, the entire human race is utterly wiped out, yet our silicon cousins are untouched. After shedding metaphorical tears over our disappearance, they then go on doing their thing- composing haunting songs (influenced by Mozart, the Beatles, and

Rachmaninoff ), writing searching novels (in English and other human languages), making hilarious jokes (maybe even ethnic and sexual ones), and so on. If we today could look into some crystal ball and see that bizarre future, would we not thank our lucky stars that we had somehow managed, by hook or by crook, to propagate ourselves into the indefinite future by means of a switchover in chemical substrate? Would we not feel, looking into that crystal ball, that “we” were still somehow alive, still somehow there? Or – would those silicon-chip creatures bred of our own fancy still be unworthy of being labeled “we” by us?•