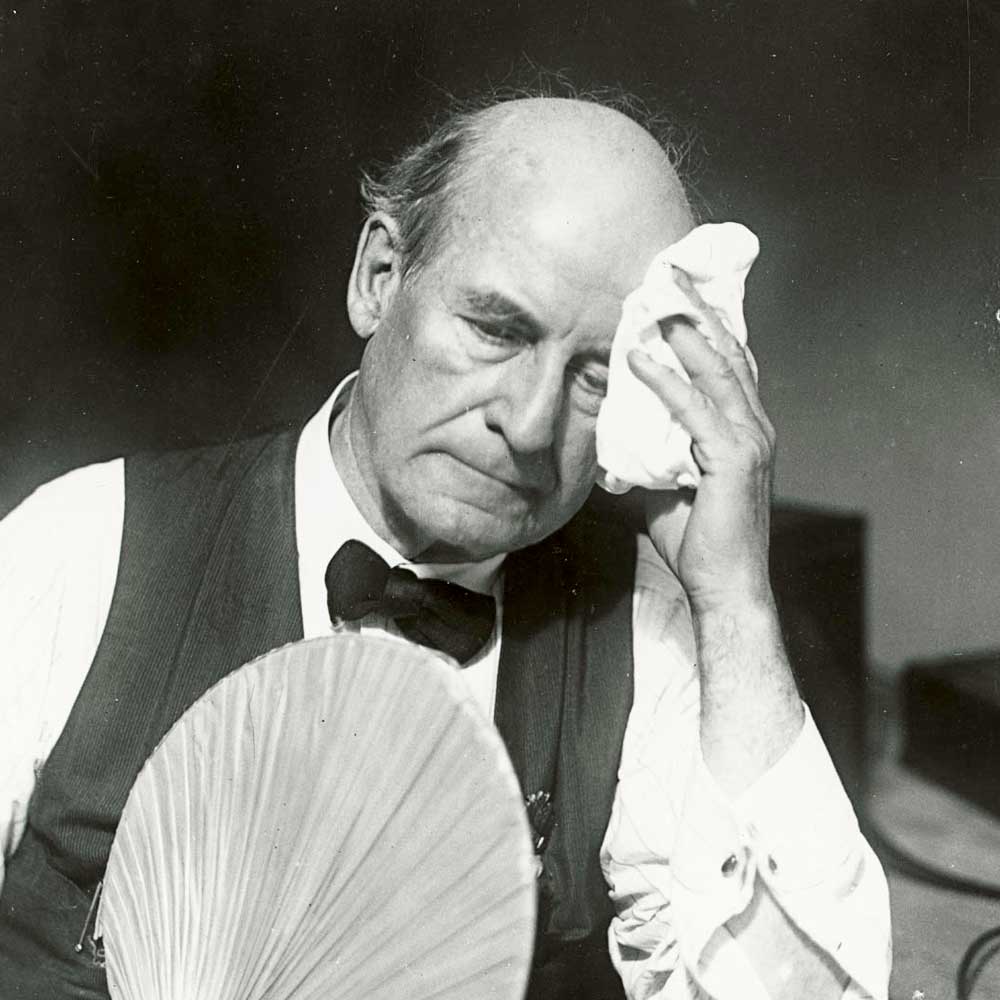

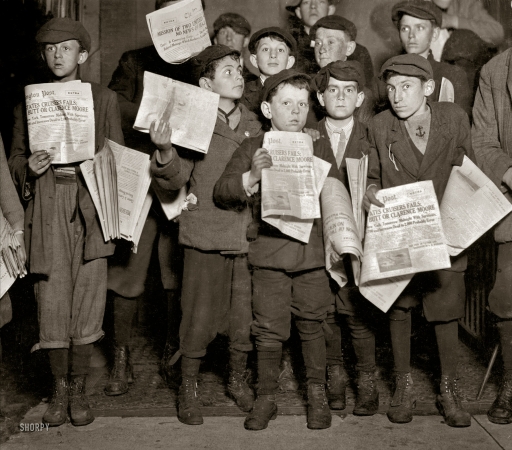

From the August 11, 1925 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

You are currently browsing the archive for the Science/Tech category.

Tags: William Jennings Bryan

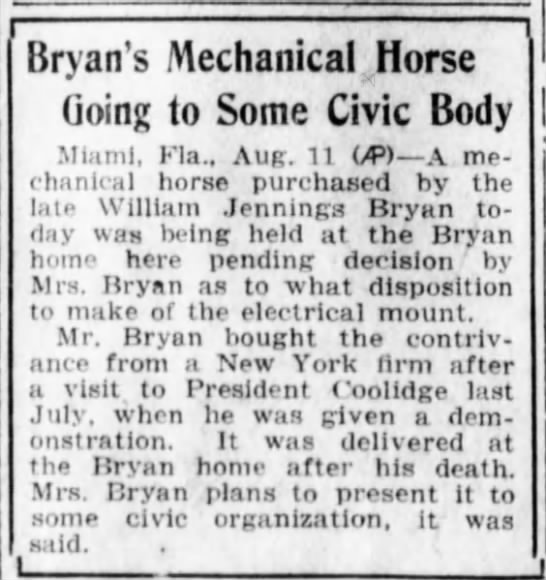

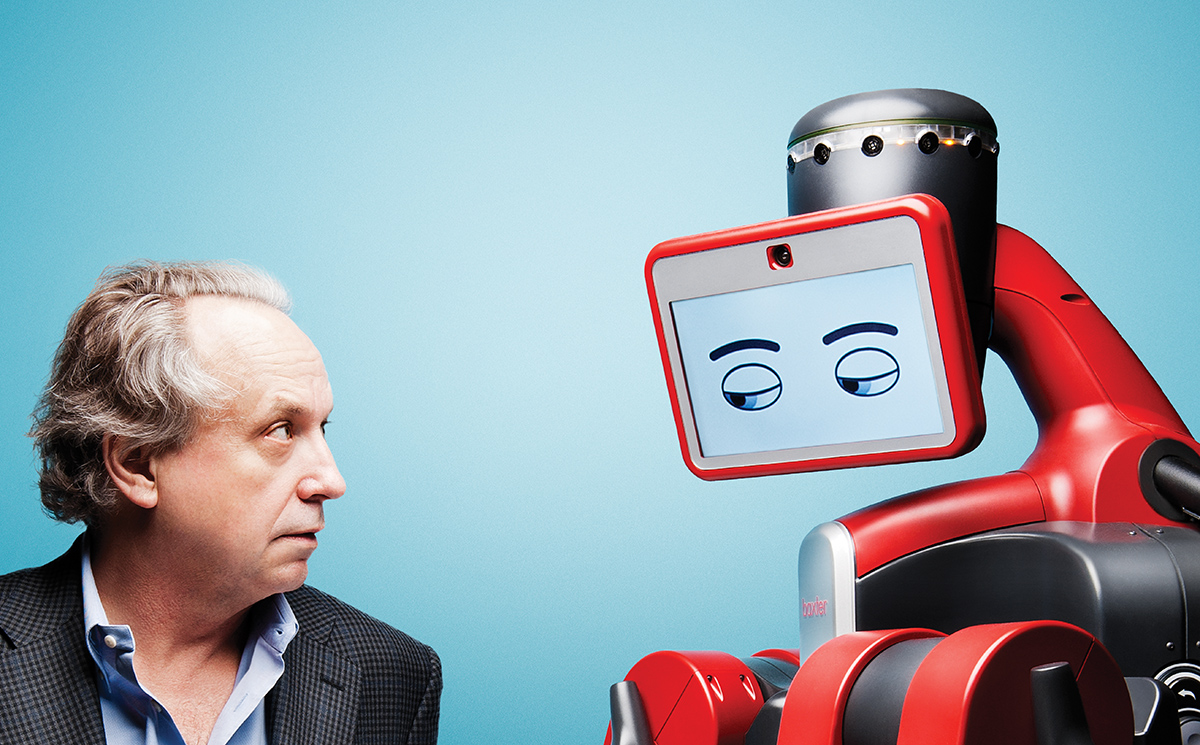

MOOCs mean more students, remote ones, who have lots of questions. To deal with the burden, Georgia Tech professor Ashok Goel, when offering an online Artificial Intelligence course, insinuated a robot Teaching Assistant powered by Watson into the proceedings. Most of the pupils never grew suspicious during their Q&As with the A.I. T.A., even a student who’d previously helped build Watson hardware. Does this demonstrate machine intelligence improving or humans becoming too passive in accepting what’s presented to them? Both, probably. It’s a dual lesson in technology and psychology.

From Melissa Korn at the Wall Street Journal:

Since January, “Jill,” as she was known to the artificial-intelligence class, had been helping graduate students design programs that allow computers to solve certain problems, like choosing an image to complete a logical sequence.

“She was the person—well, the teaching assistant—who would remind us of due dates and post questions in the middle of the week to spark conversations,” said student Jennifer Gavin.

Ms. Watson—so named because she’s powered by International Business Machines Corp.’s Watson analytics system—wrote things like “Yep!” and “we’d love to,” speaking on behalf of her fellow TAs, in the online forum where students discussed coursework and submitted projects.

“It seemed very much like a normal conversation with a human being,” Ms. Gavin said.

Shreyas Vidyarthi, another student, ascribed human attributes to the TA—imagining her as a friendly Caucasian 20-something on her way to a Ph.D.

Students were told of their guinea-pig status last month. “I was flabbergasted,” said Mr. Vidyarthi.

“Just when I wanted to nominate Jill Watson as an outstanding TA,” said Petr Bela.•

Tags: Ashok Goel, Jennifer Gavin, Melissa Korn, Petr Bela, Shreyas Vidyarthi

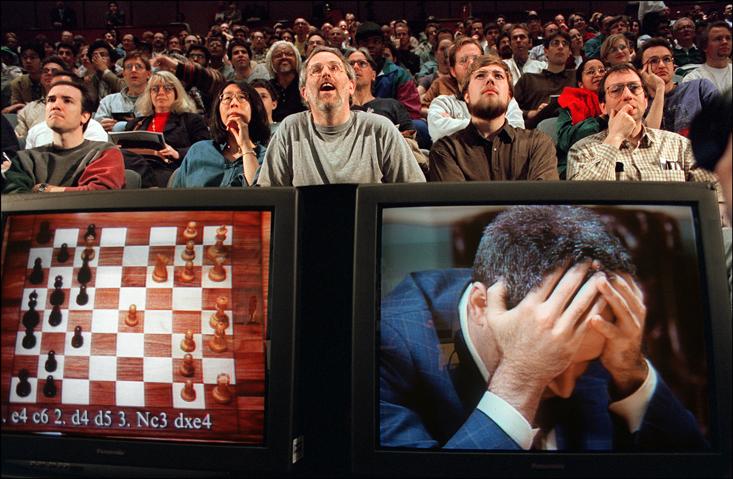

If we our species or some version of it persists long enough, conscious machines will be possible–probable, even. We’ll ultimately pull apart the vast mystery of the human brain, and unlocking those secrets will begin us on a path to making machines that are SMART, not just smart. It’s worth pursuing a Big Data workaround, a shortcut to superintelligence, but that seems less a sure thing.

In an Edge interview, psychologist Gary Marcus is concerned that the brute force of Big Data may be leading us astray in the search for Artificial Intelligence. If you recall, in late January the NYU psychologist argued the DeepMind AlphaGo system was overhyped, but by March he was proven wrong. His other questions about our ability to widely apply such an AI remain unsettled, however. Marcus feels particularly strongly that driverless cars will be hampered by real-world uncertainty.

From Edge:

If you’re talking about having a robot in your home—I’m still dreaming of Rosie the robot that’s going to take care of my domestic situation—you can’t afford for it to make mistakes. The DeepMind system is very much about trial and error on an enormous scale. If you have a robot at home, you can’t have it run into your furniture too many times. You don’t want it to put your cat in the dishwasher even once. You can’t get the same scale of data. If you’re talking about a robot in a real-world environment, you need for it to learn things quickly from small amounts of data.

The other thing is that in the Atari system, it might not be immediately obvious, but you have eighteen choices at any given moment. There are eight directions in which you can move your joystick or not move it, and you multiply that by either you press the fire button or you don’t. You get eighteen choices. In the real world, you often have infinite choices, or at least a vast number of choices. If you have only eighteen, you can explore: If I do this one, then I do this one, then I do this one—what’s my score? How about if I change this one? How about if I change that one?

If you’re talking about a robot that could go anywhere in the room or lift anything or carry anything or press any button, you just can’t do the same brute force search of what’s going on. We lack for techniques that are able to do better than just these kinds of brute force things. All of this apparent progress is being driven by the ability to use brute force techniques on a scale we’ve never used before. That originally drove Deep Blue for chess and the Atari game system stuff. It’s driven most of what people are excited about. At the same time, it’s not extendable to the real world if you’re talking about domestic robots in the home or driving in the streets.•

Tags: Gary Marcus

Would you like to survive if the sun dies? (When is actually more like it.) I would. Of course, I’ll be dead long before then, but in theory, anyway.

The sun will make Earth uninhabitable long before it completely burns out. Is it possible that our tools and technology will be so advanced in a couple hundred million years that we can “maintain” the sun or construct other ones as need be? Anything’s possible given enough time, I suppose, but other workarounds are likely more realistic.

In “How to Survive Doomsday,” an excellent Nautilus essay, Michael Hahn and Daniel Wolf Savin look at the daunting task of outlasting our star. An excerpt:

In a paltry 500 million years or so, no humans will remain on the surface of the Earth—at least, not outside of some hypothetical controlled environment. And things get worse from there. After the atmospheric CO2 is gone and no longer able to regulate Earth’s surface temperature, things will start to get very hot. In about a billion years, the average surface temperature will increase to above 45 degrees Celsius from the current 17 degrees Celsius. Important biochemical processes turn off at temperatures above 45 degrees Celsius, leaving most of the planetary surface uninhabitable. Animal life will need to migrate to the cooler poles to survive; but by 1.5 billion years from now, even the poles will be too hot. Not even cockroaches will survive.

Now, there are a few things we can do to stay our execution. We could, for example, move the Earth’s orbit. If we fired a 100 km wide asteroid on an elliptical orbit that passed close to the Earth every 5,000 years, we could slowly gravitationally nudge the planet’s orbit farther away from the sun, provided that we don’t accidentally hit the Earth. As a less precarious alternative, we could build a giant solar sail behind the Earth with enough mass to drag the planet away from the sun. Such a sail acts like a kite, where the photons from the sun are the wind and the gravity between the solar sail and the Earth acts as the string. The sail would need to have a diameter 20 times that of the Earth but a mass only about 2 percent that of Mt. Everest, a mere trillion metric tons. Strategies like these could, in principle, keep the Earth in the habitable zone until the sun expands into a red giant. (If some other civilization has already built such a large solar sail, we could detect it using the same photometric techniques that are currently used to find exoplanets.)

Another survival choice is more complicated—or simpler, depending on your perspective. The future Earth will actually be a pleasant home for non-biological life—better than it is today. For one thing, the brighter sun will provide more abundant solar power. The space weather will also be nicer. The sun is a dynamo spinning on its axis about every 24 days, generating giant magnetic storms that disrupt communication networks, overload power grids, and damage orbiting satellites. Robots today need fear that their circuits could be fried by a solar storm, such as the large solar storm in 1989 that caused a power failure across most of Quebec. Currently, such storms are estimated to occur about once or twice per century. But as the sun ages, this rotation slows down and the magnetic storms will abate.

Given these facts, we humans might simply decide to upload ourselves into machines, which would be relatively comfortable on the dystopic future Earth.•

Tags: Daniel Wolf Savin, Michael Hahn

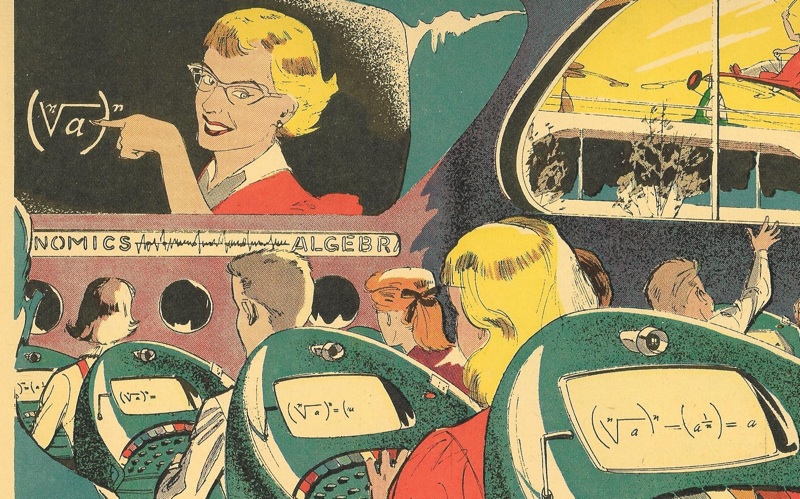

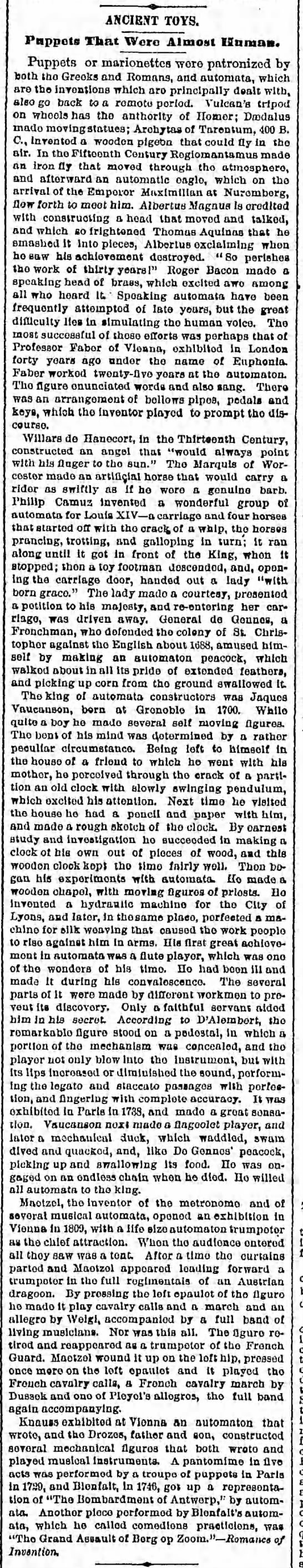

Speaking of automata through the ages, the article embedded below from the July 31, 1887 Brooklyn Daily Eagle surveys some highlights from the field, with special attention paid to 18th-century French inventor Jacques de Vaucanson, who breathed “life” into the Digesting Duck (pictured above), among other locomotion machines.

Tags: Jacques de Vaucanson

When you love yourself, even mirrors aren’t enough.

Homo sapiens have always been fascinated by looking into the glass, so much so that attempts to create machine versions of ourselves snakes back to ancient times. Machines surpassing us physically–and perhaps eventually emotionally–seem to have sneaked up on us, but it’s been a long time coming.

In “Frolicsome Engines: The Long Prehistory of Artificial Intelligence,” an excellent Public Domain Review article by Jessica Riskin, the Stanford historian writes the backstory of not only humanoid automata but efforts at all manner of simulacra. The opening:

How old are the fields of robotics and artificial intelligence? Many might trace their origins to the mid-twentieth century, and the work of people such as Alan Turing, who wrote about the possibility of machine intelligence in the ‘40s and ‘50s, or the MIT engineer Norbert Wiener, a founder of cybernetics. But these fields have prehistories — traditions of machines that imitate living and intelligent processes — stretching back centuries and, depending how you count, even millennia.

The word “robot” made its first appearance in a 1920 play by the Czech writer Karel Čapek entitled R.U.R., for Rossum’s Universal Robots. Deriving his neologism from the Czech word “robota,” meaning “drudgery” or “servitude,” Čapek used “robot” to refer to a race of artificial humans who replace human workers in a futurist dystopia. (In fact, the artificial humans in the play are more like clones than what we would consider robots, grown in vats rather than built from parts.)

There was, however, an earlier word for artificial humans and animals, “automaton”, stemming from Greek roots meaning “self-moving”. This etymology was in keeping with Aristotle’s definition of living beings as those things that could move themselves at will. Self-moving machines were inanimate objects that seemed to borrow the defining feature of living creatures: self-motion. The first-century-AD engineer Hero of Alexandria described lots of automata. Many involved elaborate networks of siphons that activated various actions as the water passed through them, especially figures of birds drinking, fluttering, and chirping.•

Tags: Jessica Riskin

As I’ve mentioned before, Google does not want to be primarily a search giant in a decade. That would leave the company in a well-appointed grave. That’s why the X division–a bold attempt at a latter-day, privately held Bell Labs–is so critical, moonshots so meaningful. If the company hits on a few, it can reinvent itself on the fly.

Of course, what’s good for an individual corporation is much more of a mixed blessing for a society. Pretty much all of these endeavors have a surveillance aspect, can only be commodified by knowing where we are, what we’re doing and what we’re thinking. They’re aimed at moving us all inside the Plex.

In a Backchannel piece, Astro Teller, X Director and true believer, culls the cutting-room-floor material from his recent TED Talk to further discuss the creative process. It’s a mix of sound advice and Silicon Valley self-mythologizing. The opening:

Almost every day in the moonshot factory is messy. Even when you’re sure you’re learning lots of valuable things during weeks or months of frustration, everyone worries, “What happens if I fail? Will people laugh at me? Will I get fired?” At the end of the day, we all have to pay the bills and want the people around us to think highly of us. So it’s human nature to gravitate toward the paths that feel psychologically safe.

That’s why, if you want your team to be audacious, you have to make being audacious the path of least resistance. People have to feel safe even as they make mistakes or fail altogether — which means we, as managers and leaders, have to make it easy and rewarding to take risks and run enthusiastically at really hard things. Here are a few things we’ve tried at X so our emotional environment keeps us brave enough to say and act on things that have a very good chance of being wrong — and just might be crazy enough to be brilliant.•

Tags: Astro Teller

Key to making driverless cars a going concern is enabling them to communicate with other vehicles, to receive constant updates, to have maps redrawn in real time. That conversation won’t only be amongst vehicles, however. It will involve all manner of smartphones and sensors and more, utilizing an Internet of Things approach in advance of a truly dense IoT.

In a Detroit News article by Neil Winton, Delphi Automotive executive Jeff Owens believes we may see fleets of driverless taxis popping up in municipalities within five years. Well, who knows? It wouldn’t stun me if someone tried it in that span, though there’ll still be lots of work to do. He touches on the connectivity issue. An excerpt:

Automotive manufacturers have made great strides in automating almost all functions, but it’s the final 5 percent which might be the hardest hurdle to jump. A self-driving car would be able to handle all kinds of physical decisions for braking, steering and avoiding other cars, but how would it handle a situation where a legal decision was required? …

“At the end of the day, technology won’t be the inhibitor, it will be the legal framework,” he said.

Owens said vehicle connectivity which allows cars to talk to each other and share data is building up ahead of full autonomy to improve safety and avoid accidents.

“Vehicle control algorithms will be ready to take on all kinds of problems including that cyclist example. Already cars like the Mercedes S class (its top-of-the-range sedan) and the Audi Q7 (SUV, and the Tesla Model S) allow you to set the auto pilot on the highway which allows hands-off driving. The driver will still be keeping watch, but it helps for a relaxed experience,” Owens said.

“Connectivity used to be just entertainment, now it’s vehicle-to-everything — literally really connected to everything like the infrastructure and providing cloud-based information that will help a safe journey,” he said.•

Tags: Neil Winton

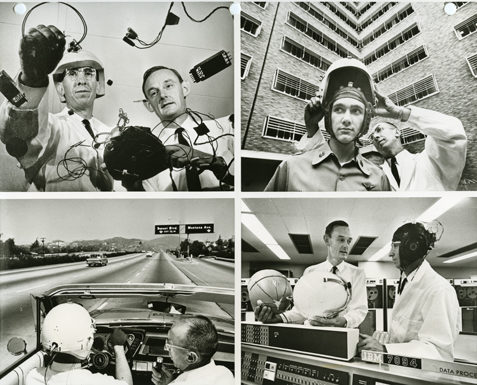

Google Glass may in some form be the future, but what a huge fiasco it was annals of product development. The narrative within the Plex is that the uncool tool was introduced to the market too soon, before all the kinks had been worked out, but that’s blind to its bigger, existential problem: It was a Segway for your face.

As an Economist piece points out, however, a vision that’s not a winner in public parks may be one within the office park. One way or another, Augmented Reality will likely become a boon companion in the workplace. The opening:

AHEAD of its time or just plain weird? Whatever the answer, Google last year stopped selling consumer prototypes of its controversial Google Glass, a camera-equipped head-mounted display resembling a pair of spectacles. Using a process known as augmented reality (AR), Glass can display in the viewer’s line of sight information about what they are looking at, among other things.

What consumers found unusual, factories and other businesses may not. Workers are often required to wear odd-looking safety equipment, such as helmets and protective glasses. It is more normal to be filmed. And indeed, the workplace is where AR equipment is taking hold, which is why Google is revamping Glass with business uses in mind.

Engineers that work on and repair transformers that distribute electricity can spend up to half their time searching for technical data in assorted software, databases, activity logs and even old-fashioned filing cabinets, says Alain Dedieu, a vice-president in the Shanghai operations of Schneider Electric. The French multinational is now testing AR systems that make the technical information that is being sought appear before their engineers’ eyes.•

Facebook doesn’t likely give a frig about journalism and cares even less for journalists. Excellent reportage may as well be Angry Birds or emoticons or some other empty calories. If Zuckerberg’s nation-state could make more money by offering absolutely no journalism, by erasing every last bit of it from the social network, it likely wouldn’t hesitate to do so. The company has absolutely no commitment to journalism, because that’s not the business Facebook is in. It’s in the money business. The company’s so-called mutually beneficial arrangement with traditional news publishers may ultimately play out like a zero-sum game.

The opening of a Gizmodo piece by Michael Nuñez about the unpleasantness of the social network’s trending-news department:

Depending on whom you ask, Facebook is either the savior or destroyer of journalism in our time. An estimated 600 million people see a news story on Facebook every week, and the social network’s founder Mark Zuckerberg has been transparent about his goal to monopolize digital news distribution. “When news is as fast as everything else on Facebook, people will naturally read a lot more news,” he said in a Q&A last year, adding that he wants Facebook Instant Articles to be the “primary news experience people have.”

Facebook’s stranglehold over the traffic pipe has pushed digital publishers into an uneasy alliance with the $350 billion behemoth, and the news business has been caught up in a jittery debate about what, precisely, the company’s intentions are. Will it swallow the business whole, or does it really just want publishers to put neat things in users’ news feeds? For its part, Facebook—which has recently begun paying publishers including Buzzfeed and the New York Times to post a quota of Facebook Live videos every week—bills its relationship with the media as a mutually beneficial landlord-tenant partnership.

But if you really want to know what Facebook thinks of journalists and their craft, all you need to do is look at what happened when the company quietly assembled some to work on its secretive “trending news” project. The results aren’t pretty: According to five former members of Facebook’s trending news team—“news curators” as they’re known internally—Zuckerberg & Co. take a downright dim view of the industry and its talent. In interviews with Gizmodo, these former curators described grueling work conditions, humiliating treatment, and a secretive, imperious culture in which they were treated as disposable outsiders. After doing a tour in Facebook’s news trenches, almost all of them came to believe that they were there not to work, but to serve as training modules for Facebook’s algorithm.•

Tags: Mark Zuckerberg, Michael Nunez

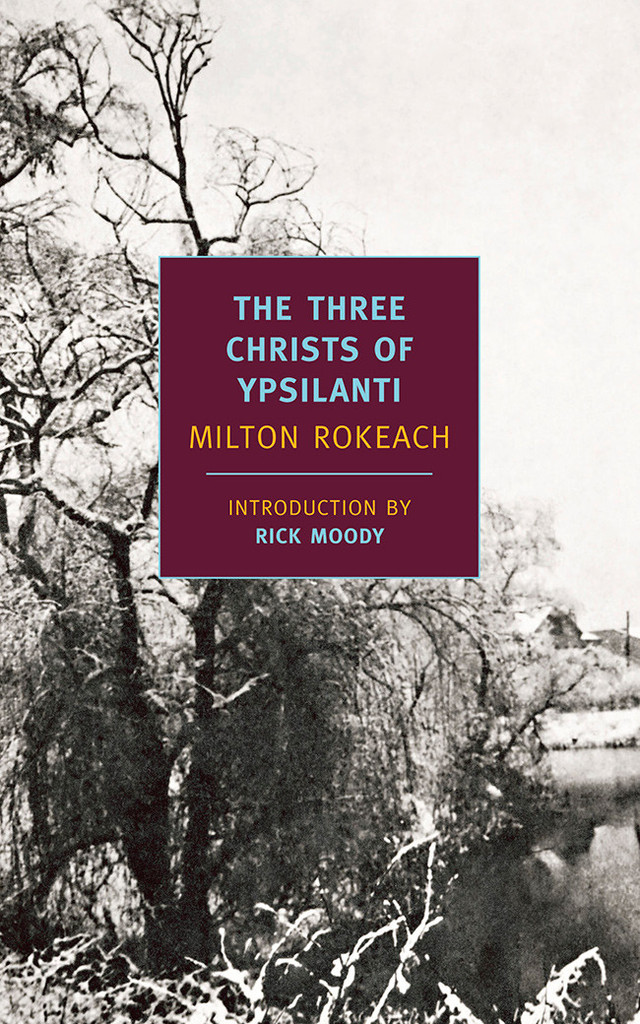

If it wasn’t for the miraculous New York Review Books imprint, I may have never read Moravagine or The Three Christs of Ypsilanti, and then where would I be? Those two are giants, and there have been a lot of other pleasures, titles by Freeman Dyson and Dorothy Baker and Robert Sheckley.

I’m not as dour about literary publishing as, say, Philip Roth. It’s been increasingly difficult in the Digital Age to monetize such a field, but I think the demand is there and will always be there, no matter how many among us are binge-watching TV or “liking” our “friends.” I can’t guarantee there will always be a Broadway, but as long as there are humans, there will be theater. Telling stories is ingrained in us. The same is true, I think, of great literature.

At the Paris Review blog, Susannah Hunnewell has a smart interview with NYRB founder, Edwin Frank. An excerpt:

Question:

Were you surprised by how successful the series has been?

Edwin Frank:

The point of the series should be to get the books out there, spread the news, and to pay its way. It does pay its way. You could say the series started at a difficult but also opportune moment in a still ongoing crisis in publishing, a difficult business. Because this last decade has been a time when more than ever books are getting pushed aside by other kinds of entertainments and sources of information, and that has been a challenge for publishers and contributed to the decline of the independent bookstore that went on for so long and seemed inevitable. But in fact it’s changed. The decline has not only stopped but been reversed, and I imagine that’s because with books and literature under siege people who really care about books and literature care about them all the more. They want to defend them and seeing them as something you have to defend can put them in new light, makes you think again. What is it I love about these things? What difference do they make? And then again for people growing up with all the gadgets, perhaps the book offers a very specific respite, a place apart, a welcomingly unsocial medium, you could say. That may be going on, too. In any case, this ancient space of books has been changed by the new economy and the new technology. It doesn’t feel the way it used to feel—it feels threatened in some ways—but you can feel it all the more and feel it’s there to explore precisely because it can’t be taken for granted. Old as it is it feels different and in fact new and I think that may help to account for the new independent bookstores opening up, as well as for the success of our series and adventurous publishers like Archipelago.•

Tags: Edwin Frank, Susannah Hunnewell

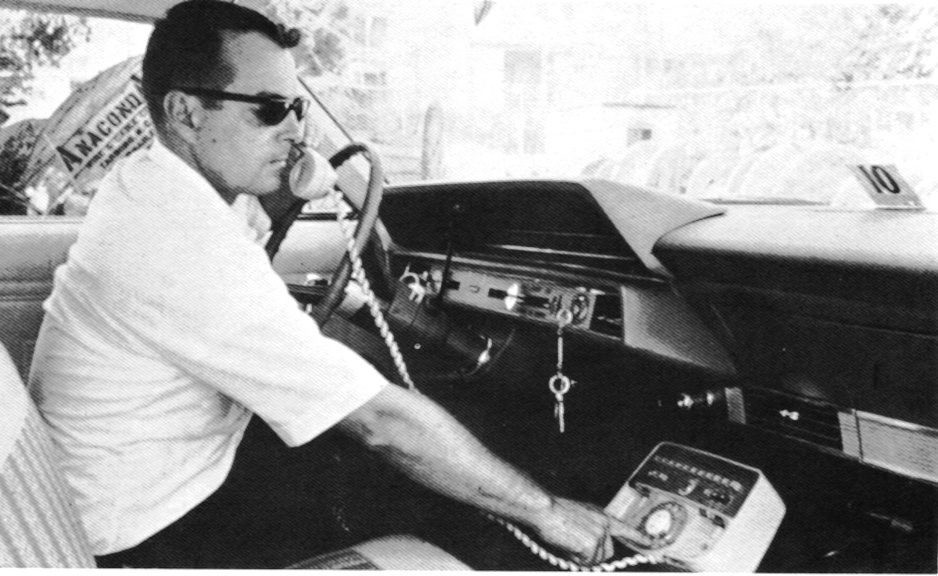

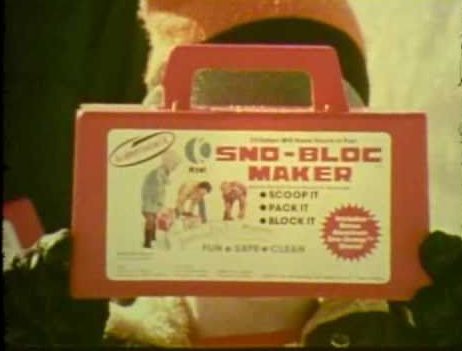

When salesmen began traveling by airwaves rather than highways, Philip Kives was the king of the road.

The Canadian-born wheeler and dealer’s company, K-Tel, had a knack for making and marketing products you didn’t really need but wanted nonetheless: Veg-O-Matics, Bonsai Knives, Sno-Bloc Makers. They were designed well, packaged handsomely, priced fairly and they sold, oh how they sold. Perhaps just as impressive as the plastic and metal pieces themselves was the tagline on the ubiquitous ads, “As Seen on TV,” which ingeniously seemed to confer some status upon the odd items while feeding our psychological need for viral, communal participation long before the Internet made instant the gratification of that urge.

The excellent New York Times writer Margalit Fox penned a postmortem of Kives, who just died. An excerpt:

If K-tel’s rhetoric seemed sprung from the lips of an old-time midway barker, there was a reason: As a young man, Mr. Kives had plied that trade, hawking cookware and other goods at county fairs and on the boardwalk of Atlantic City.

By all accounts as skilled a salesman in person as he was en masse, he was one of the last living links between the “Step right up!” pitchman of the early 20th century and his expansive electronic-age heir.

Philip Kives was all but born scrappy, in a Jewish agricultural colony near Oungre, Saskatchewan, on Feb. 12, 1929. His parents, Kiva and the former Lily Weiner, had met and married in Turkey, where they had been settled by the Jewish Colonization Association to avoid persecution in their native Eastern Europe.

In 1926, the organization resettled the Kives family once more — to a farm on the Canadian prairie with neither electricity nor running water.

Amid the Depression, they battled drought, crop failure and insect infestations that seemed to rival the biblical plagues, living for many years on welfare. Philip grew up milking cows, hauling drinking water and earning money by trapping weasels and selling their fur.

In 1957, the young Mr. Kives left the farm for Winnipeg, where he worked as a cabby and a short-order cook. He began selling sewing machines and vacuum cleaners door to door, following the wires strung over newly electrified parts of town to find and court his customers.

He soon became a Paganini of pitchmen, hawking products at fairs throughout Canada and the United States.•

When music was as much held as listened to, the Record Selector and Tape Selector came in handy.

Tags: Margalit Fox, Philip Kives

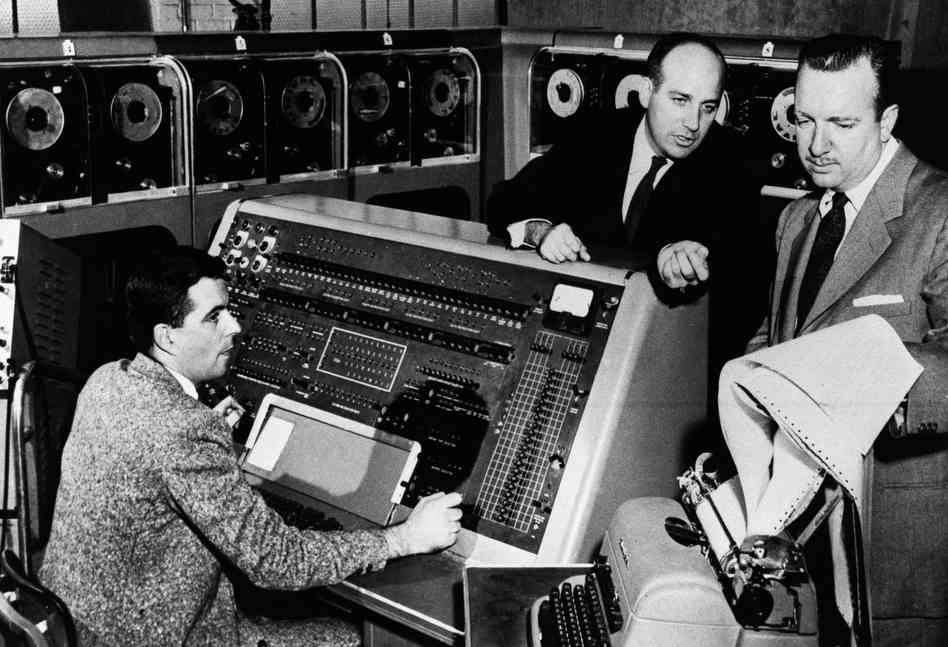

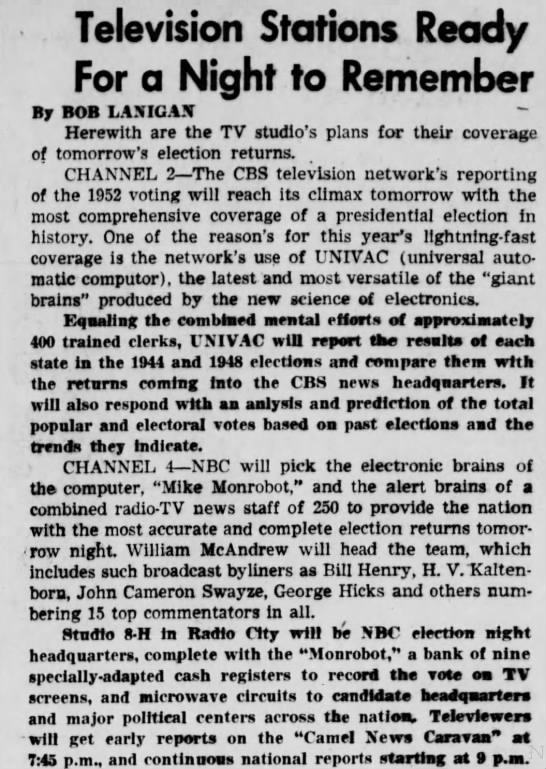

From the November 3, 1952 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

The Univac 1 computer got off to a good start in 1952 when it predicted that Eisenhower would win easily over Stevenson even though the press thought the reverse outcome was a near-certainty. It faltered a bit in the 1954 midterm Senate races and was mocked. (“Tilt!” was hollered in the newsroom by one wiseass when it became clear that the prognostications were errant.) But by the 1956 Presidential election, the computer once more nailed the Eisenhower triumph over Stevenson. No TV broadcast of any major election ever went without a computer again.

In this 1952 clip, Walter Cronkite cedes the floor the machine which at this early point in the night thought Eisenhower was a 100-1 favorite to win. Nervous CBS brass were so concerned that the “electronic brain” was wrong that they initially pretended it had mechanical difficulties and was being unresponsive.

We think we’re the captains of our own vessels, but then our brains remind us we’re merely passengers.

Some experience this phenomenon of being prone to our own heads in an even more pronounced way. In his latest excellent piece for BBC Future, David Robson writes of a man whose illness left him with a brain that created fictional “memories” for him. The effect is called “confabulation,” with the organ alternating between narratives true and untrue, with the “reader” left to fathom what’s what.

The opening:

A few months after his brain surgery, Matthew returned to work as a computer programmer. He knew it was going to be a challenge – he had to explain to his boss that he was living with a permanent brain injury.

“What actually happened at the meeting was that the employers said, ‘How can we help you, how can we make you fit back into work and get back on your feet again?’” Matthew explains. “That’s what they said. But my recollection the next day was that they were going to fire me – there was no way they could allow me back into work.”

The memory was very vivid – he says – just as believable as anything that had actually happened. Yet it was completely false. Today, Matthew knows it was one of the first signs that he was suffering from “confabulation” as a result of his brain injury. Confabulators don’t mean to lie or mislead, but some fundamental problems with the way they process memories mean they often struggle to tell fact from a fiction concocted by their unconscious mind.

The discovery was another painful blow to Matthew (whose name has been changed to preserve his privacy). “I was really scared – I thought I can’t trust what’s actually happened.”

His dilemma, although extreme, can help us all to understand the frailties of our memories, and the ways our minds construct their own versions of reality.•

Tags: David Robson

Aubrey de Grey might be right, eventually.

The gerontologist believes someone currently alive will live ten centuries, that immortality is inevitable, if we simply work to make it so. If Homo sapiens persists long enough, that might be true, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. De Grey, after all, said in 2004 that “the first person to live to 1,000 might be 60 already.” If it were so, 72-year-olds everywhere would have a right to be excited, but alas.

The scientist is still playing the 1,000-year game, as evidenced by an Express article by Jon Austin. The opening:

Dr Aubrey de Grey believes people who have already been born could live for ten centuries because of ongoing research being done into “repairing the effects of ageing.”

He hopes to ultimately create preventative treatments that mean humans would be able to consistently re-repair and live as long as 1,000 years or possible even forever.

British-born Mr de Grey, who graduated from Cambridge University in 1985 insists he is one of very few scientists looking at preventing, rather than slowing down ageing, and is perplexed why there is not huge focus on it.

He told the actuary.com: “To me, ageing was the world’s most important problem. It was so obvious that I never tested the assumption. I always presumed that everyone else thought the same.”

But his theory for repairing ageing has not been widely accepted by peers.

He said: “People have this crazy concept that ageing is natural and inevitable, and I have to keep explaining that it is not.•

Tags: Aubrey de Grey, Jon Austin

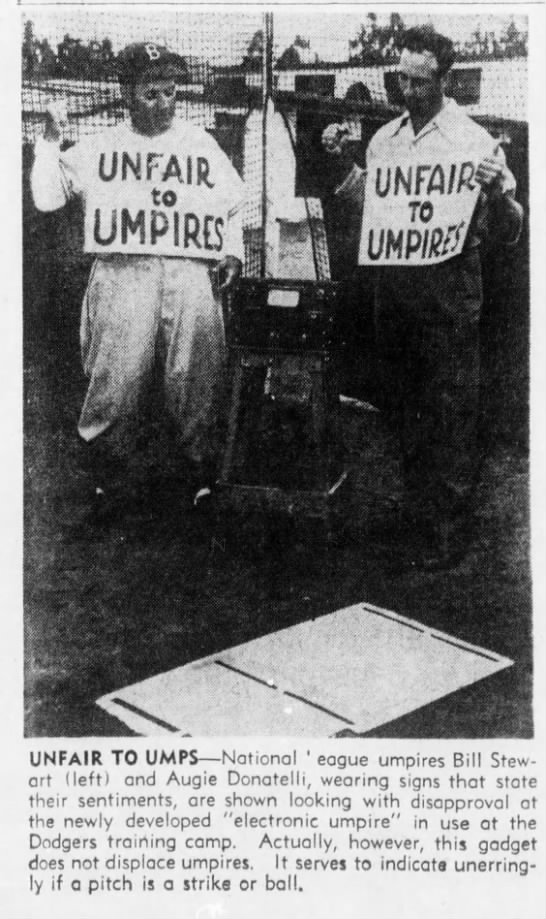

You would think someone like myself obsessed with technology, baseball and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle would have already heard of a 1950 experiment at Ebbets Field in which MLB tested an “electronic umpire.” I hadn’t, though, until reading Richard Sandomir’s smart New York Times account of such. Dodgers President Branch Rickey, who was progressive in myriad ways, including being a Moneyballer long before Beane was born, didn’t want to sweep umps from behind the plate but hoped to use the tool to make hitters more aware of the strike zone.

The sport should definitely today exploit advances in sensors and computers to automate ball and strike calls at some level of the minors, with an eye toward replacing the human element behind the catcher in the bigs. Even the best umpires are wrong on balls and strikes about 10% of the time, and that wiggle room damages the integrity of the game.

Sandomir’s opening:

One day in March 1950, a batting cage at the Brooklyn Dodgers’ spring training camp in Vero Beach, Fla., became the setting for an event that looked as if it came out of the future: strikes being called not by a man in a mask, peaked cap and chest protector, but by a machine.

“This was really high-tech stuff,” said pitcher Carl Erskine, recalling the sight of the device during a telephone interview from his Indiana home.

The so-called “cross-eyed electronic umpire” introduced that day used mirrors, lenses and photoelectric cells beneath home plate that would, after detecting a strike through three slots around the plate, emit electric impulses that illuminated what The Brooklyn Eagle called a “saucy red eye” in a nearby cabinet.

Popular Science declared, “Here’s an umpire even a Dodger can’t talk back to.”

The noted British journalist Alistair Cooke, then a foreign correspondent for The Manchester Guardian, weighed in wryly with the “alarming news” that the Dodgers would “try out an electronic umpire in the hope that he will call a decision even the Yankees will not be able to challenge.”

It was the atomic age, but sports were not known for being technologically advanced. Still, the coming decades saw much more: instant replay, slow motion, the virtual first-down line, real-time score boxes in the corner of television screens, the glowing puck, tennis-ball trackers, video review and baseball’s Pitch f/x and Statcast systems.

Chris Marinak, Major League Baseball’s senior vice president for league economics and strategy, said that sharp advances in camera and computer technology had accelerated innovation.•

Tags: Carl Erskine, Richard Sandomir

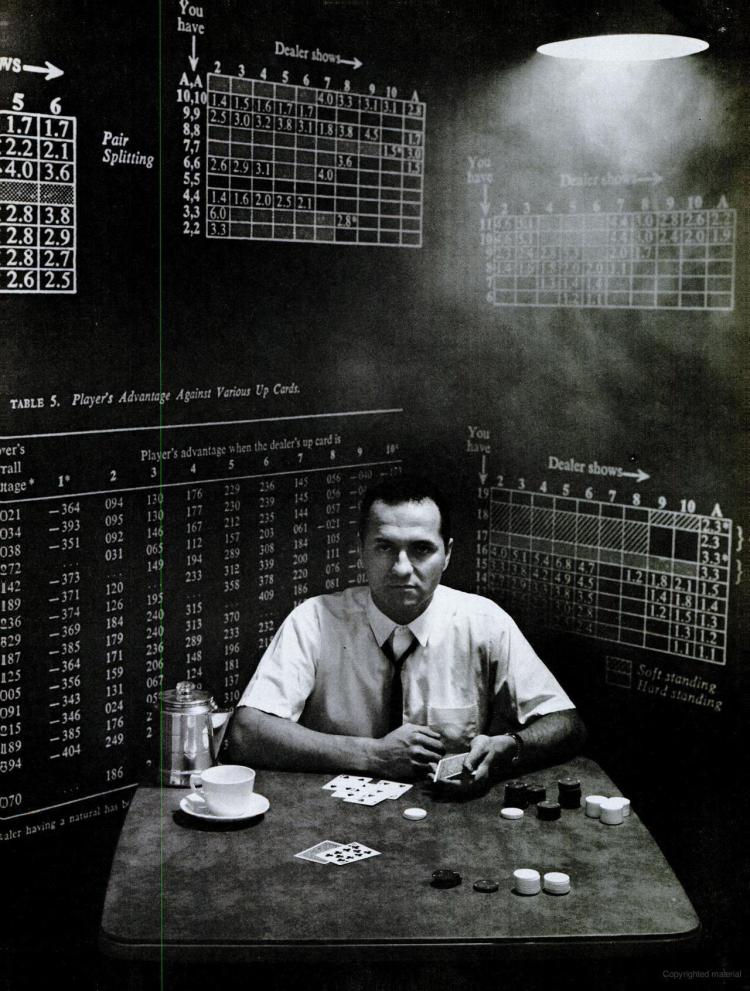

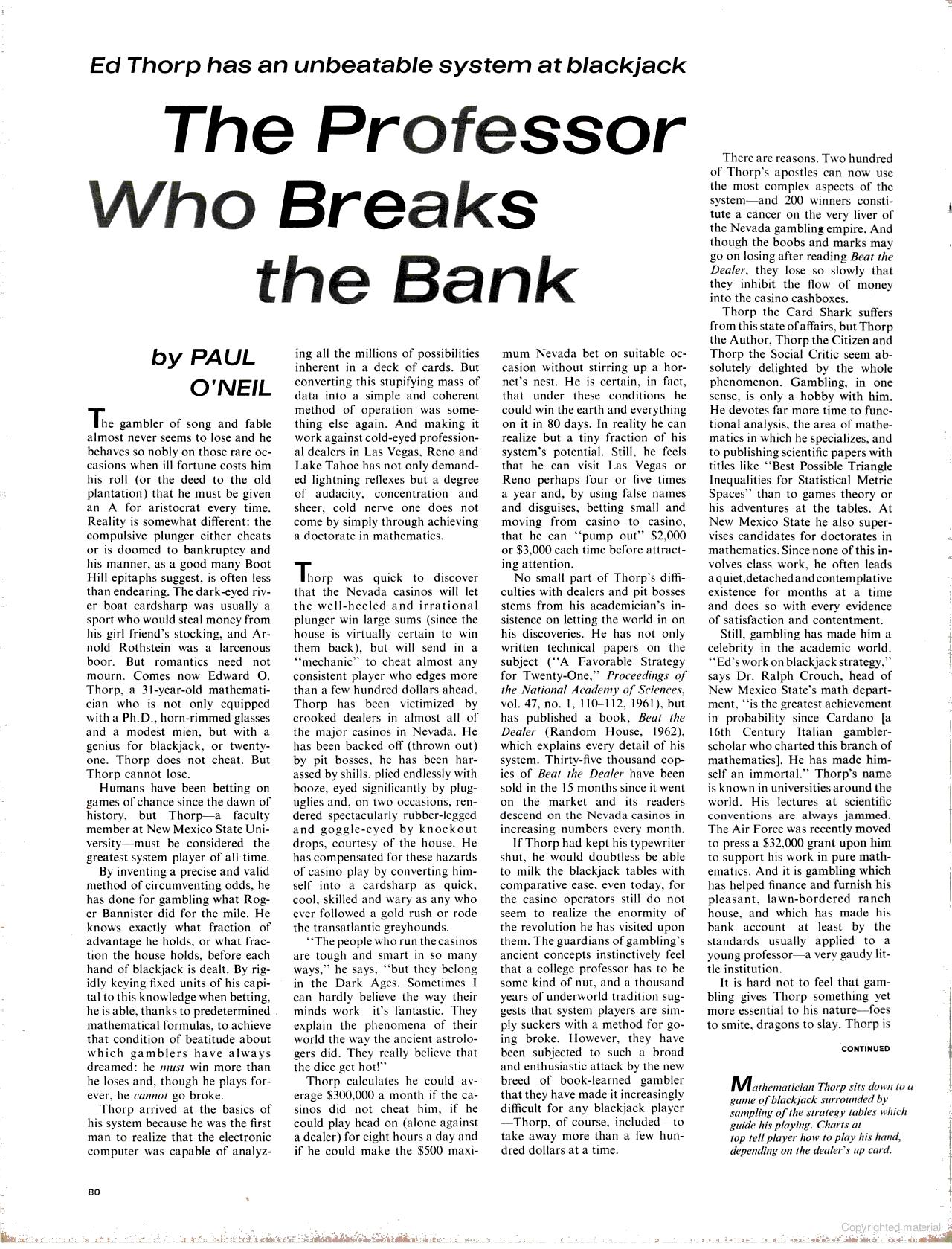

Speaking of Edward O. Thorp, who in 1955 co-created with Claude Shannon what’s accepted as the first wearable computer, Life magazine profiled the academic/gambler in 1964. The story’s hook was undeniable: a brilliant mathematician who utilized his beautiful mind at gaming tables to bring pit bosses to heel. He didn’t rely on the fictional “hot hand” but instead on cool computer calculations. What wasn’t known at the time–and what Thorp didn’t offer to reporter Paul O’Neil–is that the Ph.D. had a stealthy sidekick if he chose in the aforementioned wearable. Click on the page below for a larger, readable version of the article’s opening.

Tags: Edward O. Thorp

It’s stunning how poor people often are at reading each other’s emotions. It seems more a lack of ability than of concern. If you can discern the meaning of facial expressions and body language, you have a distinct advantage in life–and greater responsibility, whether you accept it or not.

Smart machines are said to be dumb at this skill, suggesting that if you want a safe long-term career you should opt to work in the area of emotional intelligence. That may be true but not likely for long. AI won’t need to be anything near conscious to become adept at knowing how we feel. There really don’t need to be any great breakthroughs for AI to develop emotional IQ; time and investment will make it so. The question is, will machines be responsible with this knowledge?

In a Korea Herald article, historian Yuval Noah Harari speaks to this issue. The opening:

It is no news that machines have come to largely replace physical labor and computers surpass human beings in processing data. But in the future, the development of artificial intelligence may render humans obsolete even in the realm of emotional intelligence, according to Yuval Harari.

“It is true that in one sense, AI doesn’t even come close to human emotion since it has no consciousness or mind and doesn’t feel anything,” said Harari at Tuesday’s opening ceremony of the 2030 Eco Forum, organized by Green Fund and held at the Korea Press Center. Harari is a history professor and author of the international bestseller “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind.”

Yet, AI may excel at detecting the emotional needs of human beings and reacting appropriately to them, Harari said.

“What biology tells us today is that emotions are not some spiritual experience, but the outcome of biochemical processes in the body.

“AI today is able to diagnose your personality and emotional state by looking at your face and recognizing tiny muscle movements. It can tell whether you are tired, excited, angry, joyful, in love … it can tell these things even though AI itself doesn’t feel anger or love.”

In the future, therefore, AI could “drive humans out of the job market and make many humans completely useless, from an economic perspective” in areas where human interaction was previously considered crucial, Harari said.•

Tags: Yuval Noah Harari

It was the strangest thing. In 1984, stories began to escape the San Diego Padres clubhouse about a trio of pitchers, Eric Show, Dave Dravecky and Mark Thurmond, who’d become devout members of the John Birch Society. Racist behavior that postseason directed at Claire Smith, an African-American sportswriter, brought more attention to the extreme politics of the Birchers.

It all began with Show, a sort of baseball Bobby Fischer, a troubled nonconformist and deep thinker who couldn’t fit into wider society let alone the claustrophobic confines of a bullpen or dugout. He was a self-taught jazz musician ravenous for philosophy, physics, economics and history, a seeker of truth who wandered into an Arizona bookstore and headed down the wrong aisle. The pitcher picked up a volume about John Birch and became obsessed (though he always denied any racist leanings). Excerpts follow from two stories follow about his odd life and lonely death.

From “Baseball’s Thinking Man,” by Bill Plaschke, in the 1988 Los Angeles Times:

YUMA, Ariz. — Let’s play a game. What if some real smart people with a sense of humor–people who know nothing about baseball–one day decided to invent a very good baseball pitcher.

But after giving him an elbow and shoulder and all the usual stuff, what if they decided to get tricky?

What if they gave him a love for physics? A love for studying philosophers, historians and theorists? A love for writing classical jazz?

What if on road trips, while his friends are shopping and watching movies, he is in the basement of musty libraries trying to figure out why the Earth is round?

What if at home, while many players are at the ballpark several hours ahead of the required reporting time, he is still in his home, in his second-floor office, under a bright light, studying the effect of a new foreign government or ancient civilization?

What if, before he wins 20 games, he records and produces his own record album, and co-stars in a movie? Finally, just to throw everybody off, what if they made him an open, verbal member of the ultra-conservative John Birch Society? What if . . .

Forget the what ifs. Such a pitcher exists. His name is Eric Show.

His six seasons have established him as one of the National League’s best pitchers and most unusual people.

Yet, after six seasons, another question is probably more applicable.

Why?

Why has he no close clubhouse friends? Why does everybody in there look at him so funny? Why do some think he’s selfish and arrogant? Why did some even take to calling him “Erica”? And why do things always seem to happen to him?

In 1984, his John Birch affiliation is uncovered when he is spotted passing out pamphlets at a fair, and black players think he doesn’t like them.

In 1985, he gives up Pete Rose’s record 4,192nd hit, but during the 10-minute celebration he sits on the mound, and now nobody likes him.

Last season, he hits the Chicago Cubs’ Andre Dawson in the head and must flee Wrigley Field fearing for his life. When he returns to that city this season, he has only half-jokingly claimed it will be in disguise.

Show, 31, enters the 1988 season in the final year of a $725,000 contract and at the crossroads of his baseball career.

Can he find enough peace to once again become the pitcher that won 15 games to help lead the Padres to the 1984 World Series?

Or will he continue twisting in the winds of discontent, like last season, when he went 8-16 despite a 3.84 earned-run average?

Either way, the Padres say he’s trying.

“There has been change in Eric just since the middle of last season,” Padre Manager Larry Bowa said. “In the clubhouse, away from the stadium. He’s really working at understanding and being understood.”

Show says he’s trying.

“As strange at it may seem, I have tried to be more a part of my baseball environment,” Show said carefully. “If I’m still off, it’s because I started way off.”

And whatever happens, only one thing is ever certain with Eric Show.

Something will get lost in the translation.•

From “Eric Show’s Solitary Life, and Death,” by Ira Berkow in the 1994 New York Times:

An autopsy released soon after by the coroner’s office said the cause of death was inconclusive, that is, there was no observable trauma or wounds to the body. A toxicology report would be coming in about two weeks. But in statements to the center’s staff, Show said that he was under the influence of cocaine, heroin and alcohol. He said he used four $10 bags of cocaine at about 7 that night, Tuesday night. “Didn’t like how I felt,” he said, adding that he then ingested eight $10 bags of heroin and a six-pack of beer.

The questions about Eric Show’s death are no less difficult to answer than the ones about his life. Why was he so hard on himself, such an apparently driven individual? Why was he so compulsive, or at least passionate, about almost everything he undertook?

Show (the name rhymes with cow) was known as a highly intelligent, articulate man with broad interests that ranged from physics — his major in college — to politics to economics to music. “Eric didn’t fit the mold of the typical ballplayer,” said Tim Flannery, a former Padre teammate of Show’s. “Most ballplayers were like me then; we had tunnel vision. We weren’t interested in those other things.”

Show was a born-again Christian who regularly attended Sunday chapel services as a player and sometimes signed his autograph with an added Acts 4:12, which discusses salvation as coming only from belief in Jesus Christ.

He was an accomplished jazz guitarist. Sometimes after games on the road, he would beat the team back to the hotel and play lead guitar with the band in the lounge.

He was a member of the right-wing John Birch Society, a fact the baseball world was surprised to learn in August 1984 as the Padres moved toward their first and only division title.

And he was a successful businessman with real estate holdings, a marketing company and a music store, all of which kept him in expensive clothes, with a navy-blue Mercedes and a house in an affluent San Diego neighborhood.

But other elements seemed to intrude. And ultimately, the contradictions of the best and worst in American life became a disastrous mixture that defeated him.

Beyond Statistics, Just Who Was He?

For most baseball fans, Eric Show was a decent pitcher who had once been lucky enough to make it to the World Series. But to the people who were close to him, he was, in the end, someone they did not fully know.

“He led several lives, apparently,” said Arn Tellem, his agent at the time of his death.

To Joe Elizondo, his financial consultant, and Mark Augustin, his partner in a music store, and Steve Tyler, a boyhood friend from Riverside, Calif., where both were born and raised, Show was a charming, devoted friend and a caring man. “He would give you the shirt off his back,” Elizondo said. “And he did. I once told him how much I liked a shirt he was wearing, and he said, “Here, it’s yours.” He’d stop a beggar on the street and learn he was hungry and run to a diner and bring back a hot meal for him.”

To others, though, Show could seem selfish or arrogant.

And there were the drugs. Some said Show’s drug problems began when he took injections to relieve pain in his back after surgery, and he sought more and more relief. Others wondered if he had been taking drugs before he reached the major leagues.

He may also have begun taking drugs simply because he liked the challenge of being able to handle the dreaded substance. …

His death evoked memories of two strange scenes in Show’s life, one in 1992 and the other last year.

In the spring of 1992, Show was in training camp in Arizona with the A’s. He had signed a two-year contract with them in late 1990, and managed only a 1-2 record with them in 1991. Following several mornings in which he had reported late for workouts, he showed up with both hands heavily bandaged.

He explained that he had been chased by a group of youths and had to climb a fence, and had cut himself. But what was not reported was that the police later told club officials that Show had been behaving erratically in front of an adult book store, and fled when officers approached. They finally caught him trying to climb a barbed-wire fence.

Last July, he was caught by the police when running across an intersection in San Diego and screaming that people were out to kill him, and then begged the police to kill him. He was handcuffed, and while in the back seat of the police car, he kicked out the rear window. He was taken to the county mental hospital for three days of testing. Show had admitted “doing quite a bit of crystal methamphetamine.”

It was one more startling development, one more contradiction for an athlete who, in reference to his John Birch membership, once said: “I have a fundamental philosophy of less government, more reason, and with God’s help, a better world. And that’s it.”

Always Looking For Answers

Actually, it wasn’t it. Show, as a John Birch member, also denied that he was a Nazi or a racist. In fact, he had a Hispanic financial adviser, a Jewish lawyer and agent, and black friends in baseball and his music world. People from his first agent, Steve Greenberg, to Tony Gwynn, a black teammate, agreed that he was no bigot. “He joined the Birch Society because he thought it would provide answers to how the world works,” Tellem said. “He was always looking for answers.”

Show once said, “I’ve devoted my life to learning.” Asked what he was learning, he replied, “Learning everything.”•

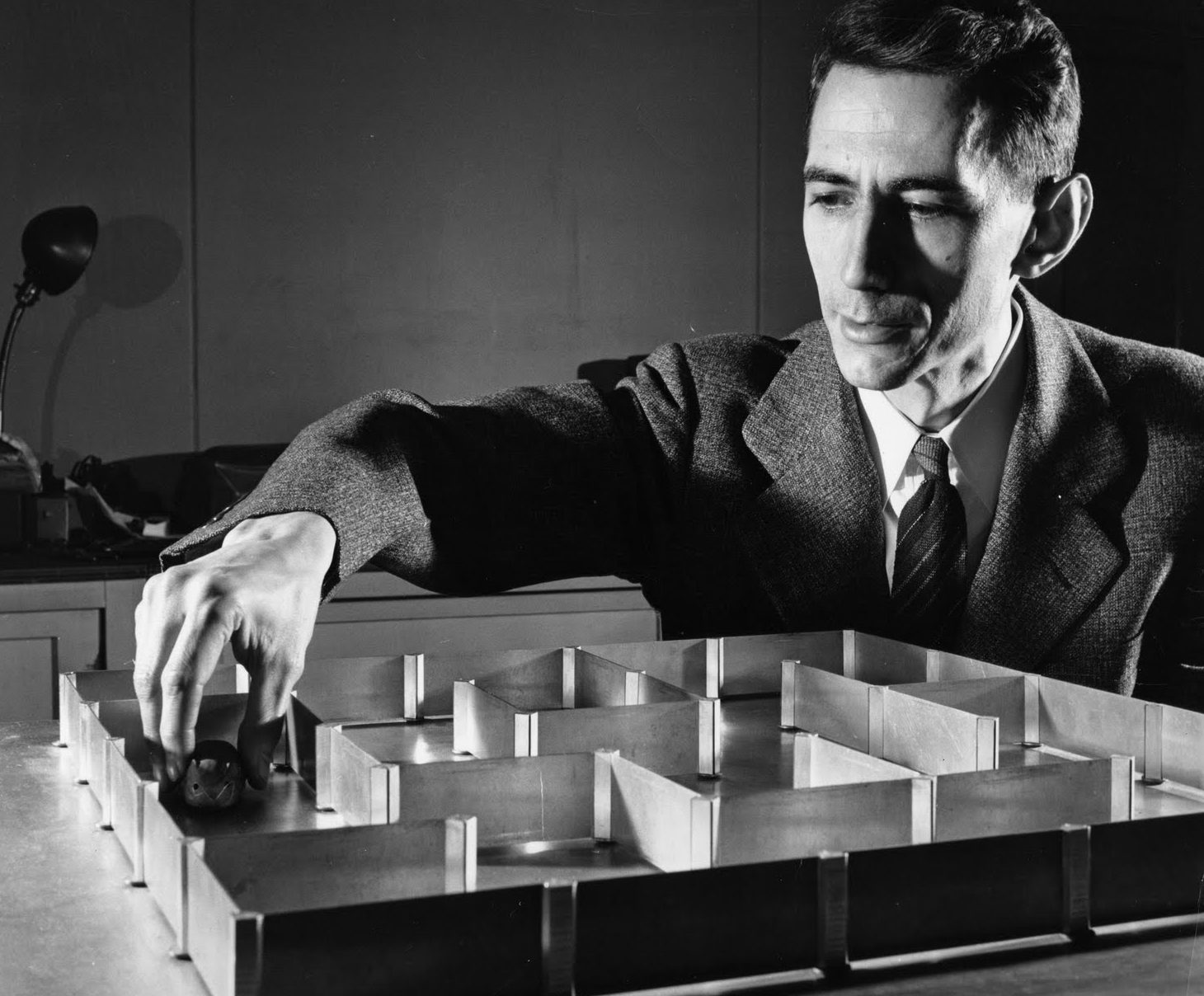

As the Google Doodle attests, Claude Shannon, the Bell Labs mastermind who did his best to invent the Information Age, would have turned 100 today. Shannon’s co-workers were often years ahead of the curve, but he was working decades in the future. In addition to knowing what the world would look like generations in advance, Shannon, a wisp of a man, was deeply eccentric and fond of games and parlor tricks. He designed the first computer chess program and the initial computerized mouse that “learned” more every time it went through a maze. (Like this, but 60 years ago.)

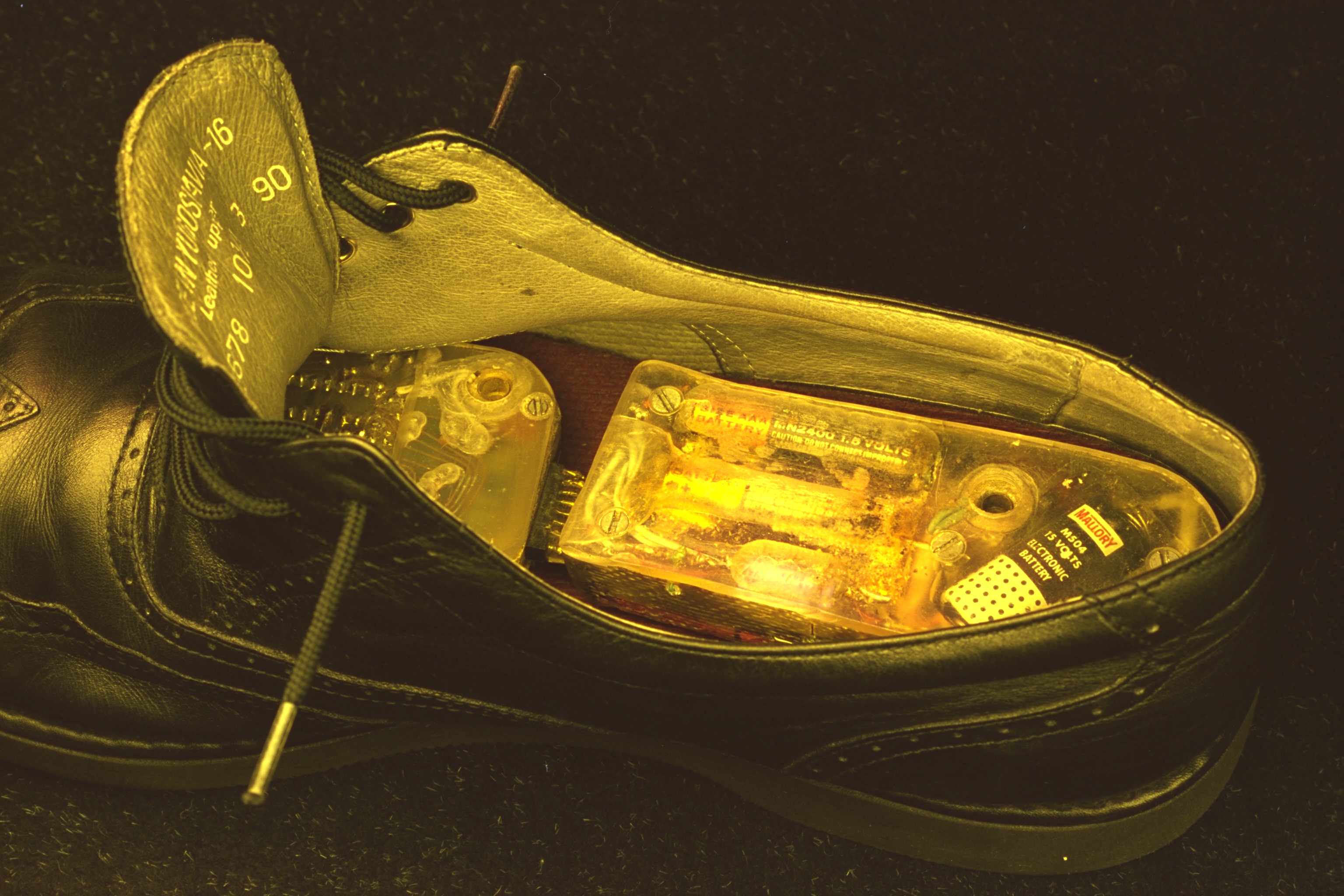

Two excerpts about him are embedded below. The first is a passage from Joel Gertner’s The Idea Factory in which recalls how the scientist’s wife, Betty, would struggle to come up with ideas for presents for her spouse, because what do you get for the man who has everything–in his head? The second is the abstract from a paper by Edward O. Thorp, a mathematics professor who lives to bring down the house–the house being a casino. He’s focused a sizable portion of his career on probability in betting games, and in 1955 he created, in tandem with Shannon, what is considered the first wearable computer. The device, which was contained in a shoe or a cigarette pack, could markedly improve a gambler’s chance at the roulette wheel, though the bugs were never completely worked out.

From Gertner:

One year, Betty gave him a unicycle as a gift. Shannon quickly began riding; then he began building his own unicycles, challenging himself to see how small he could make one that could still be ridden. One evening after dinner at home in Morristown, Claude began to spontaneously juggle three balls, and his efforts soon won him some encouragement from the kids in the apartment complex. There was no reason, as far as Shannon could see, why he shouldn’t pursue his two new interests, unicycling and juggling, at Bell Labs, too. Nor was there any reason not to pursue them simultaneously. When he was in the office, Shannon would take a break from work to ride his unicycle up and down the long hallways, usually at night when the building wasn’t so busy. He would nod to passerby, unless he was juggling as he rode. Then he would be lost in concentration. When he got a pogo stick, he would go up and down the hall on that, too.

Here, then, was a picture of Claude Shannon, circa 1955, a man–slender, agile, handsome, abstracted–who rarely showed up on time for work, who often played chess or fiddled with amusing machines all day; who frequently went down the halls juggling or pogoing, and who didn’t seem to care, really, what anyone thought of him or his pursuits. He did what was interesting. He was categorized, still, as a scientist. But it seemed obvious that he had the temperament and sensibility of an artist.•

From Thorp:

The first wearable computer was conceived in 1955 by [Thorp] to predict roulette, culminating in a joint effort at M.I.T. with Claude Shannon in 1960-61. The final operating version was rested in Shannon’s basement home lab in June of 1961. The cigarette pack sized analog device yielded an expected gain of +44% when betting on the most favored “octant.” The Shannons and Thorps tested the computer in Las Vegas in the summer of 1961. The predictions there were consistent with the laboratory expected gain of 44% but a minor hardware problem deferred sustained serious betting. They kept the method and the existence of the computer secret until 1966.•

Thorp appeared on To Tell the Truth in 1964. He didn’t discuss wearables but his book about other methods to break the bank. Amusing that longtime NYC radio host John Gambling played one of the impostors.

In 2011, Foxconn promised a million robots would be installed in its factories within three years. That did not transpire. Overzealous promises by a large corporation, however, shouldn’t be mistaken for epic failure on a national scale. For China, it’s just a dream deferred and likely not by much.

The nation is not only hugely populous but also overwhelmingly graying, desperately needing autonomous machines to take up the slack. Perhaps, as Daniel Kahneman has prophesied, “Robots will show up in China just in time.” That may be so, but some of the country’s younger workers will be destabilized by the transition, and what’s necessary in China may be extremely tumultuous for other countries with markedly different demographics.

In “China’s Robot Revolution,” Ben Bland of the Financial Times looks at the future arriving in a hurry, writing that “the benefits of the robot revolution will not be shared equally across the world.” You wouldn’t want to be living in a country that’s left behind in the Second Machine Age, but progress will have its costs. The opening:

The Ying Ao sink foundry in southern China’s Guangdong province does not look like a factory of the future. The sign over the entrance is faded; inside, the floor is greasy with patches of mud, and a thick metal dust — the by-product of the stainless-steel polishing process — clogs the air. As workers haul trolleys across the factory floor, the cavernous, shed-like building reverberates with a loud clanging.

Guangdong is the growth engine of China’s manufacturing industry, generating $615bn in exports last year — more than a quarter of the country’s total. In this part of the province, the standard wage for workers is about Rmb4,000 ($600) per month. Ying Ao, which manufactures sinks destined for the kitchens of Europe and the US, has to pay double that, according to deputy manager Chen Conghan, because conditions in the factory are so unpleasant. So, four years ago, the company started buying machines to replace the ever more costly humans.

Nine robots now do the job of 140 full-time workers. Robotic arms pick up sinks from a pile, buff them until they gleam and then deposit them on a self-driving trolley that takes them to a computer-linked camera for a final quality check.

The company, which exports 1,500 sinks a day, spent more than $3m on the robots. “These machines are cheaper, more precise and more reliable than people,” says Chen. “I’ve never had a whole batch ruined by robots. I look forward to replacing more humans in the future,” he adds, with a wry smile.•

Tags: Ben Bland

Speaking of psychodrama, the theatrical therapy is mentioned briefly in John Markoff’s Machines of Loving Grace, in a passage about the nascent career of of roboticist Rodney Brooks, who became widely known from the Errol Morris documentary Fast, Cheap & Out of Control. Even though the connection in this case is glancing, it’s a good metaphor for how low- and high-tech attempts to understand consciousness overlap historically.

The passage:

Hans Moravec, an eccentric young graduate student, was camping in the attic of SAIL, while working on the Stanford Cart, an early four-wheeled mobile robot. A sauna had been installed in the basement, and psychodrama groups shared a lab space in the evenings. Available computer terminals displayed the message “Take me, I’m yours.” “The Prancing Pony”–a fictional wayfarer’s inn in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings–was a mainframe-connected vending machine selling food suitable for discerning hackers. Visitors were greeted in a small lobby decorated with an ungainly “You Are Here” mural echoing the famous Leo Steinberg New Yorker cover depicting a relativistic view of the most important place in the United States. The SAIL map was based on a simple view of the laboratory and the Stanford campus, but lots of people had added their own perspectives to the map, ranging from placing the visitor at the center of the human brain to placing the laboratory near an obscure star somewhere out on the arm of an average-sized spiral galaxy.

It provided a captivating welcome for Rodney Brooks, another new Stanford graduate student. A math prodigy from Adelaide, Australia, raised by working-class parents, Brooks had grown up far from the can-do hacker culture in the United States. However, in 1969–along with millions of others around the world–he saw Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Like Jerry Kaplan, Brooks was not inspired to train like an astronaut but was instead seduced by HAL, the paranoid (or perhaps justifiably suspicious) AI.

Brooks puzzled about how he might create his own AI, and arriving at college, he had his first opportunity. On Sundays he had solo access to the school’s mainframe for the entire day. There, he created his own AI-oriented programming language and designed an interactive interface on the mainframe display. Brooks now went to writing theorem proofs, thus unwittingly working in the formal, McCarthy-inspired artificial intelligence tradition. Building an artificial intelligence was what he wanted to do with his life.•

Tags: John Markoff, Rodney Brooks

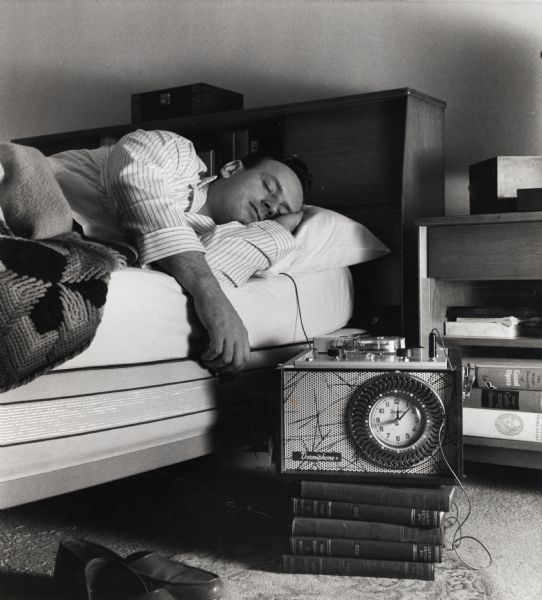

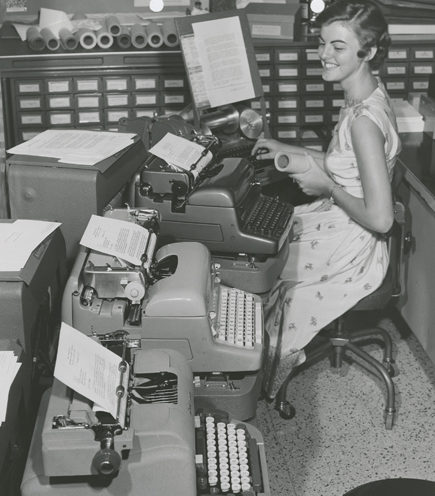

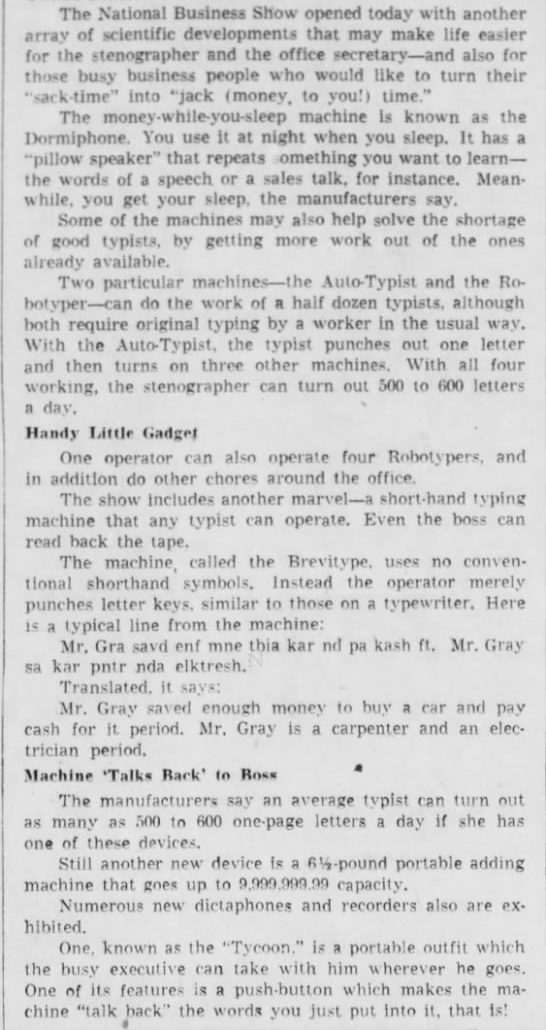

War dividends of the technological kind snaked in many directions in mid-century America, from kitchen appliances to bowling-ball return machines to business gadgets. In the latter category, new machines reaching the market promised greater automation, the ability to listen and talk and memory augmentation. These are areas reaching a significantly more mature phase now, with Siri and such. An article in the October 24, 1950 Brooklyn Daily Eagle introduced readers to the Dormiphone, the Auto-Typist, the Robotyper and the Tycoon (and Lady Tycoon) soundscriber.

Blue jeans and rock & roll, or something similar, may have won the Cold War, which was ultimately a cultural and economic one for all the rockets and bombs, but robots may be the key to victory in the coming 25 years.

In Geoff Dyer’s latest insightful Financial Times piece, the Washington-based correspondent writes the Pentagon is investing heavily in robotics and AI in an effort to keep the U.S. ahead of China and Russia as a military power in the next great arms race. I would think bioengineering will also be a part of the gamesmanship, though how far it will unfold in the next quarter century is TBD. The large sums being spent and the competition among different states with varying priorities are the reasons why I believe AI and automation will move into areas that are troubling, even if we promise ourselves something else.

In Dyer’s article, he asks five questions he believes central to the topic. An excerpt:

How far along is the military robotics revolution?

The Pentagon hails its approach as its third great technological surge since the second world war. The first was the development of battlefield nuclear weapons in the 1950s to deter a possible Soviet invasion of western Europe; the second, the development of precision strike weapons, which started in the mid-1970s and came of age during the 1991 Desert Storm campaign against Saddam Hussein.

Asked how far along the current strategy is, [Pentagon second-in-command Robert] Work says: “We are in 1976 and a period of experimentation. It is not until you see it in battle that anyone really trusts it.” He adds: “Five years from now, we will have some confrontation and we will say: ‘Holy crap, something has happened here,’ and it will start to accelerate more.”•

Tags: Geoff Dyer, Robert Work

It’s hard to conjure a more perfect example of the dual nature on contemporary industry and technology, the boon and the bane, then Tesla’s reason for being confident about the Chinese market. The head-spinning transformation of that state has lifted millions from poverty–and delivered to them the world’s worst air pollution and highest cancer rates. Elon Musk’s EVs promise to filter air inside the vehicle so that it’s 800 times cleaner than Beijing’s oxygen. Just make sure you’re door is not ajar.

From CNBC:

If you’ve ever taken a deep breath in Beijing, you’ll understand why Tesla is so excited about “bioweapon defense mode.”

Given China’s well-documented problems with air quality, Tesla is hoping the cabin-filtering feature will be a major selling point as it expands sales of its electric cars there.

“One of the most interesting features for the Chinese market is the bioweapon defense mode,” said Jon McNeill, head of global sales and service for Tesla, in an interview with Chinese broadcaster CCTV that was posted on Twitter Wednesday.

“It creates air that’s 800 times cleaner than the outside air,” he added.•

Tags: Elon Musk, Jon McNeill