In the 1990s, it was often said that Salon was the future of journalism. In the saddest possible way, that’s pretty much what happened.

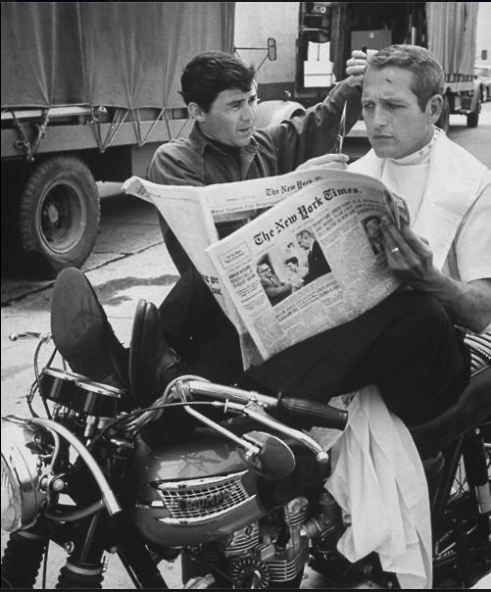

If the rise of the Internet meant lots of great traditional news publications were usurped by wonderful new online ones, something roughly equal to what was lost would have been gained. It’s possible we could even have come out ahead. As the mighty have been laid low, however, the great publications of tomorrow never arrived. Salon still publishes some talented writers, but its grand ambitions have been long buried under a mountain of debt and now makes desperate attempts at clickbait. The world’s best publications, from the New York Times to the Guardian to the Financial Times, all soldier on wounded, hopefully not mortally, as digital revenue hasn’t come close to replacing vanished print advertising dollars.

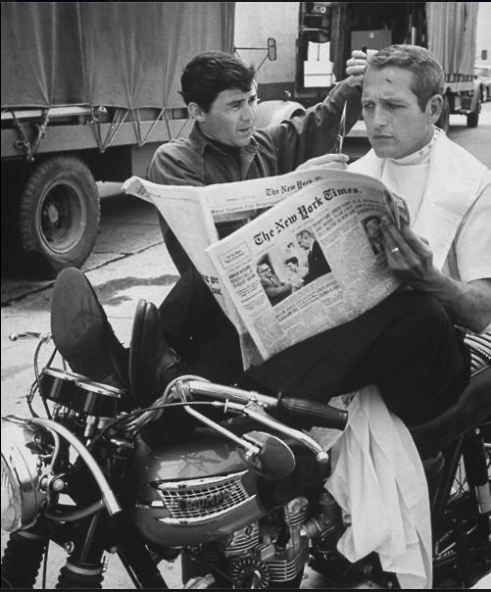

Occasionally, these publications report on each other’s decline. The New York Times, which recently covered the chaos at the Las Vegas Review-Journal, is going through its own latest round of turbulence. The New York Post is routinely gleeful about the Times’ troubles, though even during greener times, Rupert Murdock’s crummy tabloid lost tens of millions a year and has no business-related reason to exist. Vanity Fair also has a report on the latest turmoil at the Times, which will likely end in hundreds of layoffs. Of course, Conde Nast has gone through its own rounds of deep staff cuts and now seems to be pinning part of its future on video, which may be more false idol than savior.

It’s not so much a circular firing squad as a wake attended only by the walking dead.

Excerpts from two articles follow: 1) Kelsey Sutton and Peter Sterne’s Politico piece “The Fall of Salon.com,” and 2) Sarah Ellison’s Vanity Fair report “Can Anyone Save the New York Times From Itself?“

From Politico:

Eleven current and former staffers also said Daley assigned staffers to write repeatedly about certain subjects that he believed would drive high traffic. If traffic was too low, according to six former staffers, Daley would go into the CMS and write posts himself, often posting them under the byline “Salon Staff.” To improve the amount of traffic on Saturdays and Sundays, certain staffers were asked to work over the weekend and post short video clips from television programs like “The Daily Show.”

It became harder to find “high-quality” work amid all the clutter. Twelve current and former employees said they were discouraged from doing original journalism out of a concern that time spent reporting could be better spent writing commentary and aggregate stories. Even the site’s marquee names, like Walsh and Miller, were expected to produce quick hits and commentary on trending topics, staffers said.

The strategy alienated some of Salon’s longtime journalists.

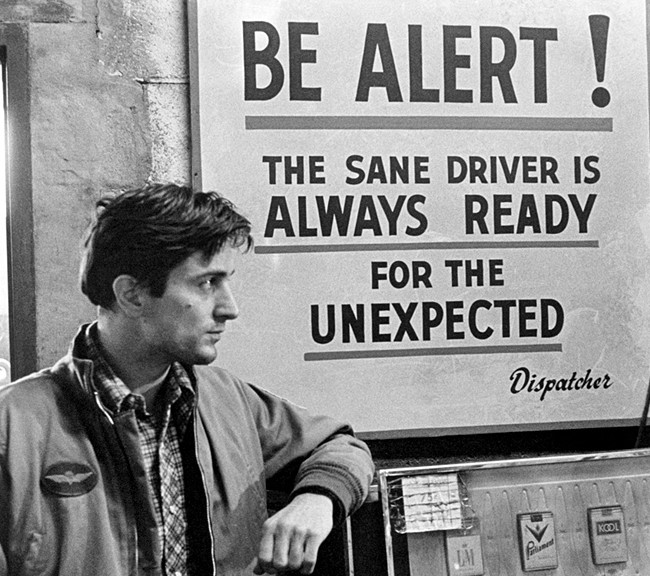

“The low point arrived when my editor G-chatted me with the observation that our traffic figures were lagging that day and ordered me to ‘publish something within the hour,’” Andrew Leonard, who left Salon in 2014, recalled in a post. “Which, translated into my new reality, meant ‘Go troll Twitter for something to get mad about — Uber, or Mark Zuckerberg, or Tea Party Republicans — and then produce a rant about it.’ … I performed my duty, but not without thinking, ‘Is this what 25 years as a dedicated reporter have led to?’ That’s when it dawned on me: I was no longer inventing the future. I was a victim of it. So I quit my job to keep my sanity.”•

From Vanity Fair:

As such, in February, former economics reporter and Washington bureau chief David Leonhardt was tasked with re-examining the entire structure of the newsroom. In the past, layoffs have been treated as a numbers game. Now, larger questions are being asked about the existence of sections and the traditional desk structure. There’s also much more pressure to toe the business line. In his announcement of Leonhardt’s role, Baquet referenced “cost” twice. “It’s made everyone uneasy,” one editor told me. Soon after Leonhardt’s appointment, the New York Post reported that the Times was preparing to lay off a “few hundred staffers.”

Times spokespeople dismissed the report, but a few days later the company announced the dismissal of 70 employees in its Paris editing and production facility alone. In May, the company announced a new round of buyouts, a move largely seen as a precursor to at least 200 newsroom layoffs early next year, according to three Times staffers. “Every time this happens,” one former editor told me, “it’s a dark cloud that hangs over the newsroom for months.” Prior to the buyout announcement, Baquet put out a memo explaining that the newsroom “will have to change significantly—swiftly and fearlessly.” When I asked him about the “at least 200” figure, he said, “I’ve said there will be cuts, but I don’t know what the right size is at this point.”

It is impossible to imagine a world without The New York Times. But it is also increasingly impossible to imagine how The New York Times, as it is currently configured, continues to exist in the modern media world.•