Once humans conjured a Creator, they placed him in the past, in the beginning, the progenitor of us all. But what if a supreme being exists at the far end of the narrative? Many have wondered about this possibility, that some superintelligence controls us from the future, but decades ago theoretical physicist Jack Sarfatti tried to prove it on a scientific basis, believing it may be possible for us to construct a “future machine.”

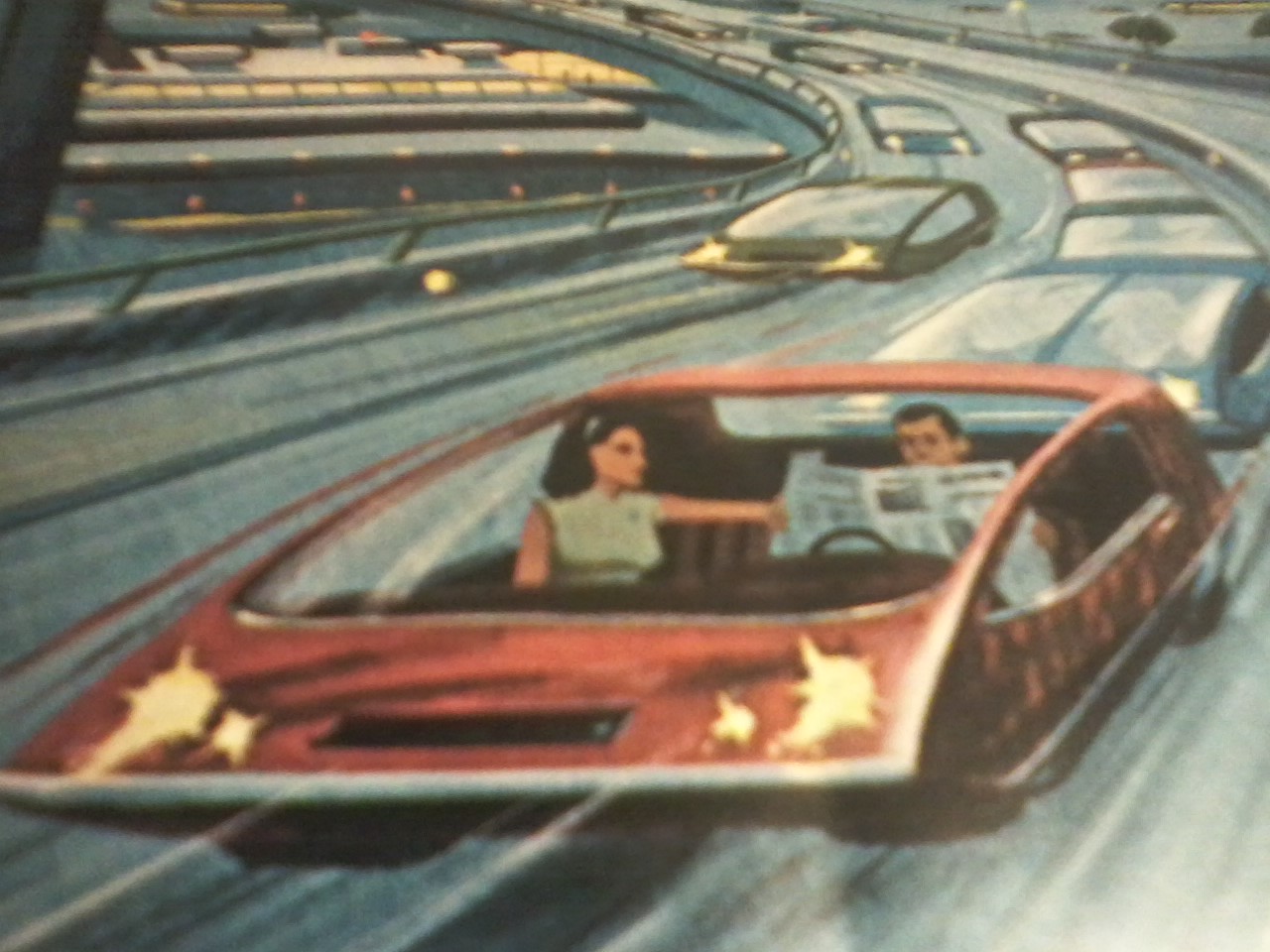

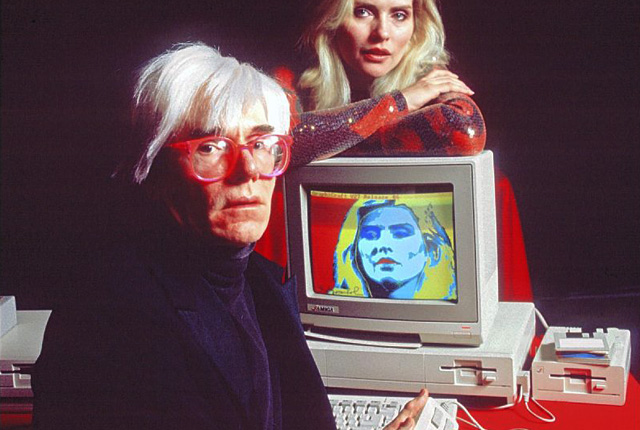

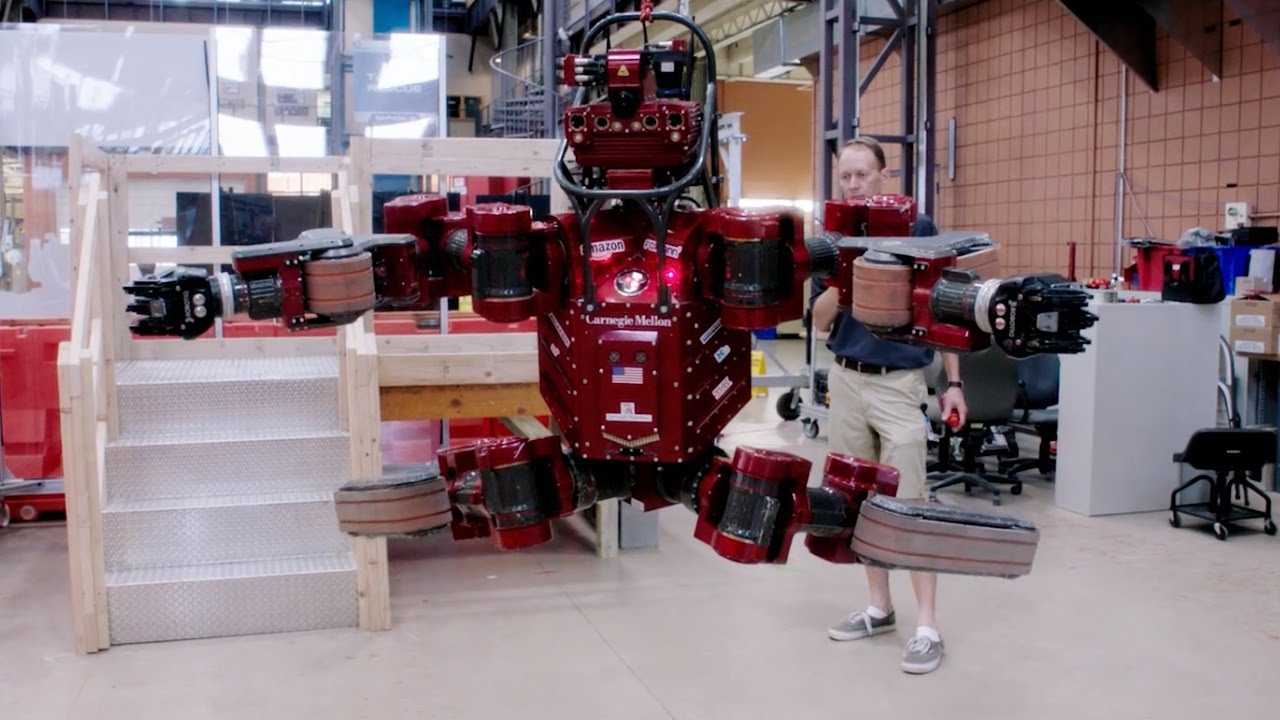

“If the future machine works, we become gods,” he said in Alex Cain’s “Jack Sarfatti’s Future Machine,” an article in the inaugural 1984 issue of High Frontiers, which billed itself as the “Space Age Newspaper of Psychedelics, Science, Human Potential, Irreverence & Modern Art.” Sarfatti had a vision for the future (and the past and present) that was incredibly FAR and decidedly OUT, a precursor to Nick Bostrom’s idea (and Elon Musk’s contention) that we are merely creations of tomorrow’s intelligence, prone to its plans for us, characters in its game.

Sarfatti was central to the synthesis of early hacker culture and the final drops of the acid-soaked one, attempting to drive the Further bus through a wormhole. In the ’84 piece, Sarfatti made this proposal: “That’s the real meaning of Abraham’s covenant with God, in the Old Testament. God is simply the intelligence of the future, talking backwards in time to the prophets. That’s what revelation is all about, in this theory. Jesus Christ was a time-traveler from the future. Let’s put it this way. Jesus himself may have been born of Mary, but his mind was imprinted by the superintelligence.” If a 2011 Vice article is any indication, Sarfatti still clings to his unproven belief and doesn’t suffer fools–or even polite, intelligent interviewers–gladly.

On the same topic, Joshua Rothman recently penned a smart New Yorker blog post, using Musk’s Bostrom bender as a jumping-off point to ponder the possibility that all the men and women are merely players in a game–a simulated game from the future. The writer wonders if it matters if we live in a simulation, which it does, for two important reasons: 1) If such a god exists, responsible for genocide and natural disasters, he isn’t just an absentee father but rather a child abuser, and 2) Calvinism in cyberspace would remove all agency from humans. An excerpt:

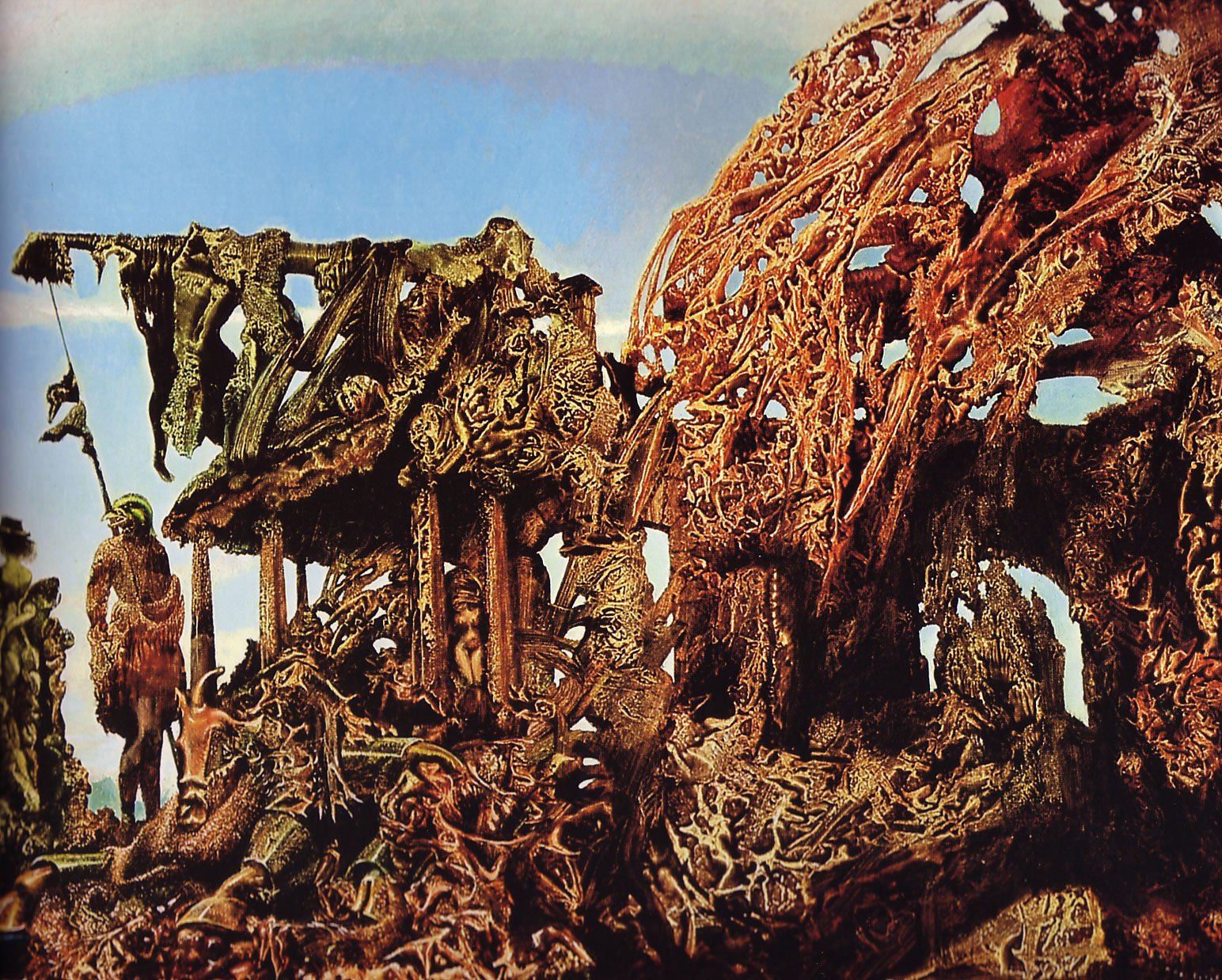

Does it matter that we might be living in a simulation? How should we feel about that prospect? Artists and thinkers have come to various conclusions. The idea of living as a “copy” in a simulated world was explored, for example, in “Permutation City,” a 1994 novel by the science-fiction writer Greg Egan, which imagines life in the early days of simulation-creation. The protagonist, a computer scientist named Paul Durham, becomes his own guinea pig, scanning his brain into a computer to create two Pauls; while the original Paul remains in the real world, the digital Paul lives in a simulated one, which is a little like a modern video game. Standing in his simulated apartment and looking at a painting—Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights”—Paul can’t quite forget that, when he turns around, the simulation will stop rendering it, reducing it to “a single gray rectangle” in an effort to save processing cycles. If we live in a simulated world, then the same thing could be happening to us: Why should a computer simulate every atom in the universe when it knows where our eyes aren’t looking? Simulated people have reasons to be paranoid.

There’s also something melancholy about the idea of simulated life: the thrill of achievement is compromised by the possibility that everything has already happened to our descendants. (Presumably, they find it interesting to watch us fight the battles they have already lost or won.) This sense of belatedness is the theme of “The Talos Principle,” a somber and captivating video game by the Croatian studio Croteam. In the game, a plague has begun to wipe out humanity and, in a desperate bid to preserve something of our history and culture, human engineers have built a small simulated world populated by self-editing computer programs. Over time, the programs improve themselves, and you play as their descendent, a conscious program living long after the demise of humanity. Wandering through picturesque ruins of human civilizations (Greece, Egypt, Gothic Europe), you encounter fragments of ancient human texts—“Paradise Lost,” the Egyptian Book of the Dead, Kant, Schopenhauer, e-mails, blog posts—and wonder what it’s all about. The game suggests that simulated life is inescapably elegiac. Even if Elon Musk succeeds in colonizing Mars, he won’t be the first one to do so. History, in a sense, has already happened.•