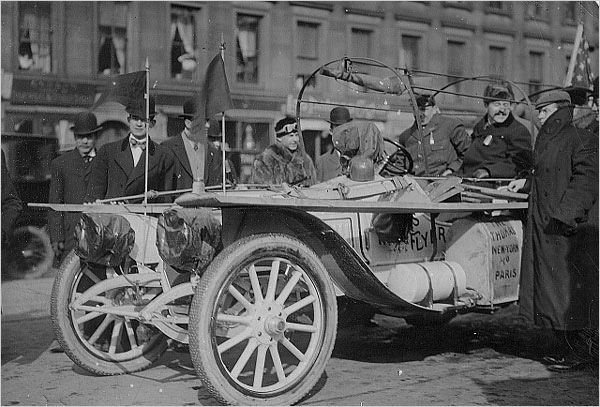

George Schuster, driver of the Thomas Flyer that won the New York-to-Paris “Great Race” of 1908, appears on I’ve Got a Secret five decades later. Prior to Schuster’s trek, no “automobilist” had driven across America during the winter.

You are currently browsing the archive for the Science/Tech category.

Tags: George Schuster

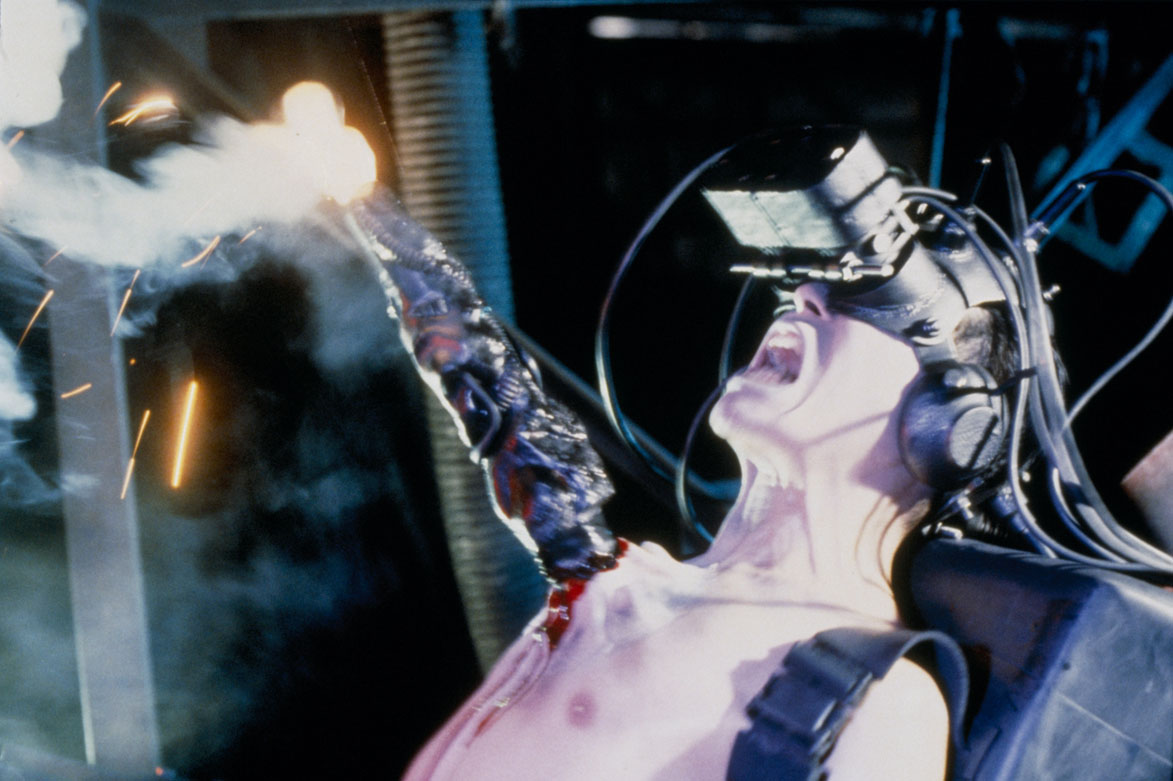

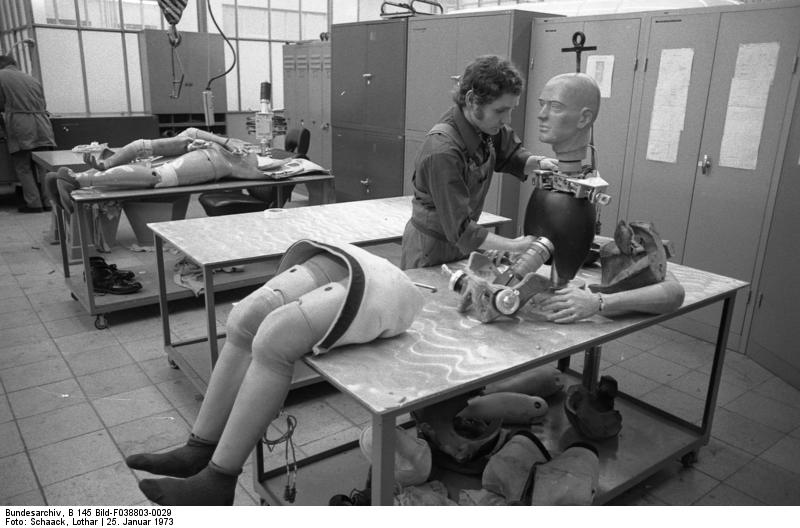

I’ve never used an illegal drug in my life, so I’m the last person who would suggest other people turn themselves into pharmaceutical guinea pigs. And bio-hackers don’t only experiment with drugs, but with all sorts of gizmos they insert beneath their skin, hoping to push human evolution to its next phase. I think they’re crazy, but it still hard to criticize them.

What pioneering enterprise isn’t fraught with danger? Those who moved westward in America making Manifest Destiny possible were taking huge risks, and a number of them died. Astronauts exploring space for NASA (and for us) take great chances, and a number of them have perished. But I can’t say either gamble lacked great value. Now that a lot of exploration has moved inside of us, I likewise can’t condemn bio-hackers and their experimentation. It probably will lead to greater knowledge, but, you know, you go first. From “Grinders: The Cult of the Man Machine,” by Leo Benedictus at the Guardian:

“A common procedure is to implant a strong neodymium magnet beneath the surface of a person’s skin, often in the tip of the ring finger. This causes nearby magnetic fields – and even their strength and shape – to become detectable to the user, thanks to the subtle currents they provoke. For a party trick, they can also pick up metal objects or make other magnets move around.

Calling this a procedure, though, gives rather the wrong impression. Biohacking is not a field of medicine. Instead it is carried out either at home or in piercing shops, cleanly and carefully with a scalpel, but without an anaesthetic (which you need a licence for). If you think this sounds painful, you are correct.

Britain is the birthplace of modern transhumanism, as the field is known. Probably the most sophisticated implantation ever made can be found inside the left arm of Kevin Warwick, professor of cybernetics at the University of Reading, who can now control a robot arm by moving his own. The system also works the other way, so he can now sense his wife’s movements in his own body, after she had a similar implantation.”

Tags: Leo Benedictus

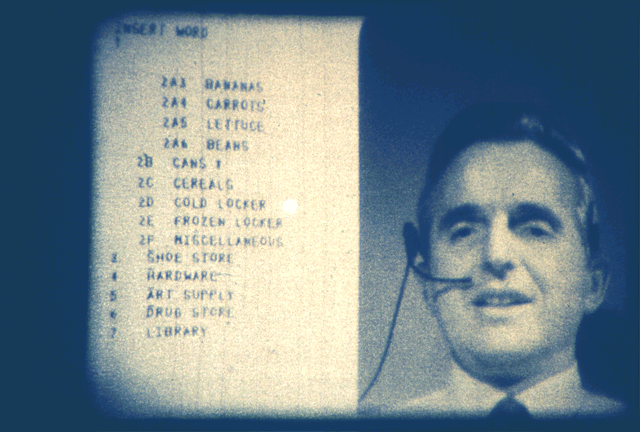

From Mark Potts’ Recovering Journalist (via the Atlantic), the opening of a 1992 letter by Bob Kaiser, Managing Editor of the Washington Post, which pinpointed exactly where print news was headed:

“August 6, 1992

To: Don Graham, Alan Spoon, Ralph Terkowitz. Tom Ferguson, Tuesday Group Vice Presidents

From: Bob Kaiser

John Sculley’s invitation to attend an Apple-organized conference

on the future of ‘multimedia’ – computers, telecommunications,

television and other entertainment media, and traditional news

media – gave me a good opportunity to learn and to think about The

Post’s place in a fast-changing technological environment. This is

a brief report on the conference and thoughts that occurred to me

while attending.

+ + +

Alan Kay, sometimes described as the intellectual forefather of the

personal computer, offered a cautionary analogy that seemed to

apply to us. It involves the common frog. You can put a frog in a

pot of water and slowly raise the temperature under the pot until

it boils, but the frog will never jump. Its nervous system cannot

detect slight changes in temperature.

The Post is not in a pot of water, and we’re smarter than the

average frog. But we do find ourselves swimming in an electronic

sea where we could eventually be devoured — or ignored as an

unnecessary anachronism. Our goal, obviously, is to avoid getting

boiled as the electronic revolution continues.

I was taken aback by predictions at the conference about the next

stage of the computer revolution. It was offered as an

indisputable fact that the rate of technological advancement is

actually increasing. Dave Nagel, the impressive head of Apple’s

Advanced Technology Group, predicted “the three billions” would be

a reality by the end of this decade: relatively cheap personal

computers with a billion bits of memory (60 million is common

today), with microprocessors that can process a billion

instructions per second (vs. about 50 million today) that can

transmit data to other computers at a billion bits per second (vs.

15-20 million today). At that point the PC will be a virtual

supercomputer, and the easy transmission and storage of large

quantities of text, moving and still pictures, graphics, etc., will

be a reality. Eight years from now.

I asked many purported wizards at the conference if they thought

Nagel was being overoptimistic. None thought so. The machines he

envisioned will have the power to become vastly more user-friendly

than today’s PC’s. They will probably be able to take voice

instructions, and read commands written by hand or an electronic

notepad, or right on the screen. None of this is science fiction –

– it’s just around the corner.”

Tags: Bob Kaiser, Mark Potts

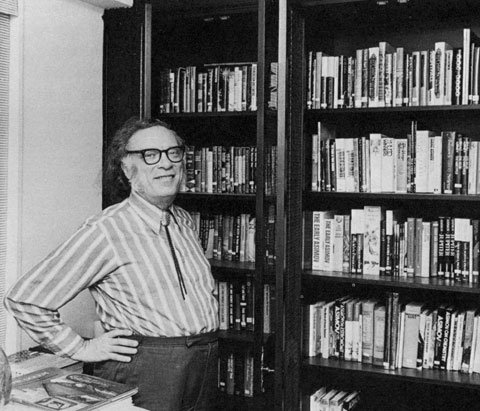

A section from a great bundle of ideas about the future of books presented by China Miéville in a lecture at the Edinburgh International Book Festival:

“In fact what’s becoming obvious – an intriguing counterpoint to the growth in experiment – is the tenacity of relatively traditional narrative-arc-shaped fiction. But you don’t radically restructure how the novel’s distributed and not have an impact on its form. Not only do we approach an era when absolutely no one who really doesn’t want to pay for a book will have to, but one in which the digital availability of the text alters the relationship between reader, writer, and book. The text won’t be closed.

It never was, of course – think of the scrivener’s edit, the monk’s mashup – but it’s going to be even less so. Anyone who wants to shove their hands into a book and grub about in its innards, add to and subtract from it, and pass it on, will, in this age of distributed text, be able to do so without much difficulty, and some are already starting.

One response might be a rearguard clamping down, as in the punitive model of so-called antipiracy action. About which here I’ll only say – as someone very keen to continue to make a living from writing – that it’s disingenuous, hypocritical, ineffectual, misunderstands the polyvalent causes and effects of online sharing, is moribund, and complicit with toxicity.” (Thanks Browser.)

Tags: China Miéville

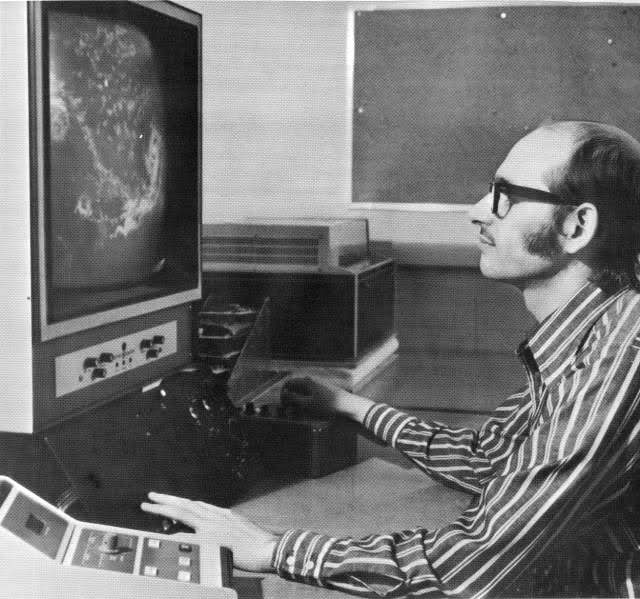

So strange and wonderful: In 1972, Rod Serling introduces I’ve Got a Secret host Steve Allen to the home version of the video game Pong. Begins at the 15:40 mark.

Tags: Rod Serling, Steve Allen

Who really knows what the economic future holds for China? But that country is currently pouring huge amounts of money into infrastructure, trying to create an advantage for its next several generations. From “Cities of the Future: Made In China,” Dustin Roasa’s new Foreign Policy article, which collects many of that country’s boldest ideas for tomorrow and beyond:

“For much of the 20th century, the world looked to American cities for a glimpse of the future. Places like New York and Chicago had the tallest skyscrapers, the newest airports, the fastest highways, and the best electricity grids.

But now, just 12 years into the Asian Century, the city of the future has picked up and moved to China. No less than U.S. Vice President Joe Biden recognized this when he said not long ago, ‘If I blindfolded Americans and took them into some of the airports or ports in China and then took them to one in any one of your cities, in the middle of the night … and then said, ‘Which one is an American? Which one is in your city in America? And which one’s in China?’ most Americans would say, ‘Well, that great one is in America.’ It’s not.’ The speech raised eyebrows among conservative commentators, but it points out the obvious to anyone who has spent time in Beijing, Hong Kong, or Shanghai (or even lesser-known cities like Shenzhen and Dalian, for that matter).

In these cities, visitors arrive at glittering, architecturally arresting airports before being whisked by electric taxis into city centers populated by modular green skyscrapers. In the not-so-distant future, they’ll hop on traffic-straddling buses powered by safe, clean solar panels. With China now spending some $500 billion annually on infrastructure — 9 percent of its GDP, well above the rates in the United States and Europe — and with the country’s population undergoing the largest rural-to-urban migration in human history, the decisions it makes about its cities will affect the future of urban areas everywhere. Want to know where urban technology is going? Take the vice president’s advice and head east.”

Tags: Dustin Roasa

We tell ourselves stories in order to live, yes, but what if we are telling the wrong stories? The ones that flatter our egos, drive us into the false security of a mythical past instead of an uncertain future, expand our delusions? From Firmin DeBrabander in the New York Times:

“In Chisago County, Minn., The Times’s reporters spoke with residents who supported the Tea Party and its proposed cuts to federal spending, even while they admitted they could not get by without government support. Tea Party aficionados, and many on the extreme right of the Republican party for that matter, are typically characterized as self-sufficient middle class folk, angry about sustaining the idle poor with their tax dollars. Chisago County revealed a different aspect of this anger: economically struggling Americans professing a robust individualism and self-determination, frustrated with their failures to achieve that ideal.

Why the stubborn insistence on self-determination, in spite of the facts? One might say there is something profoundly American in this. It’s our fierce individualism shining through. Residents of Chisago County are clinging to notions of past self-reliance before the recession, before the welfare state. It’s admirable in a way. Alternately, it evokes the delusional autonomy of Freud’s poor ego.

These people, like many across the nation, rely on government assistance, but pretend they don’t. They even resent the government for their reliance. If they looked closely though, they’d see that we are all thoroughly saturated with government assistance in this country: farm subsidies that lower food prices for us all, mortgage interest deductions that disproportionately favor the rich, federal mortgage guarantees that keep interest rates low, a bloated Department of Defense that sustains entire sectors of the economy and puts hundreds of thousands of people to work. We can hardly fathom the depth of our dependence on government, and pretend we are bold individualists instead.”

Tags: Firmin DeBrabander

The opening of “Welcome to the Future Nauseous,” a really fun Venkat Rao essay that argues that the future is always arriving and that we are unwilling or unable to process and acknowledge it so we instead assign it to some distant point:

“Both science fiction and futurism seem to miss an important piece of how the future actually turns into the present. They fail to capture the way we don’t seem to notice when the future actually arrives.

Sure, we can all see the small clues all around us: cellphones, laptops, Facebook, Prius cars on the street. Yet, somehow, the future always seems like something that is going to happen rather than something that is happening; future perfect rather than present-continuous. Even the nearest of near-term science fiction seems to evolve at some fixed receding-horizon distance from the present.

There is an unexplained cognitive dissonance between changing-reality-as-experienced and change as imagined, and I don’t mean specifics of failed and successful predictions.

My new explanation is this: we live in a continuous state of manufactured normalcy. There are mechanisms that operate — a mix of natural, emergent and designed — that work to prevent us from realizing that the future is actually happening as we speak. To really understand the world and how it is evolving, you need to break through this manufactured normalcy field. Unfortunately, that leads, as we will see, to a kind of existential nausea.” (Thanks TETW.)

Tags: Venkat Rao

Some scientists believe that space elevators, which would replace dangerous and costly rocket launchers and lift crafts into orbit rather than blasting them there, may be just a decade away. That doesn’t seem like a realistic timeline even if we master the concept, though further down the line it’s plausible. From Richard Hollingham at the BBC:

“Rockets are dangerous, complicated and relatively unreliable. No-one has yet built a launcher that is guaranteed to work every time. A misaligned switch, loose bolt or programming error can lead to disaster or, with a human crew, a potential tragedy.

Rockets are also incredibly expensive – even the cheapest launch will set you back some $12 million, meaning the cost of any cargo costs a staggering $16,700 per kilogram. Although the funky new space planes being developed, such as Britain’s Skylon or Virgin’s SpaceShipTwo, will slash the costs of getting into space, they are still based on rocket technology – using sheer brute force to escape the clutches of gravity.

But there is a radical alternative. Science fiction fans have long been familiar with space elevators. Popularised by Arthur C Clarke, the concept of an elevator from the Earth to orbit has been around for more than a century. In the space operas of Iain M Banks or Alastair Reynolds, space elevators are pretty much taken for granted – they’re what advanced civilisations use to leave their planets.”

Tags: Richard Hollingham

It’s not April 1st, so I’ll trust this Gizmodo story by Tom Pritchard which reports that an Israeli theme park has enabled donkeys with wi-fi. The opening:

“Step aside Hobo Wi-Fi, there’s a new, better way for people to get their internet on the go. Introducing Wi-Fi enabled donkeys from Israel – ancient transport now updated for the 21st century.

Kfar Kedem is a historical theme park with the purpose of reenacting life as it was 2000 years ago, including the ever popular donkey ride, now with a twist. Currently five of the donkeys are walking Wi-Fi hotspots with future plans to expand to the other 25 donkeys the park owns. If you ever take a visit it, watch yourself in case you’re run over by a wayward child on the back of the donkey who’s too busy Instagramming to look where he’s going.”

Tags: Tom Pritchard

You can keep going around in this circle for a long time: Criminals who have brain defects have less control over their actions so judges have a tendency to give them shorter sentences so they are returned sooner to society where they have less control over their actions. That’s at least the in vitro conclusion drawn from a recent experiment that presented neurobiological evidence to judges in hypothetical cases. From Benedict Carey in the New York Times:

“In the study, three researchers at the University of Utah tracked down 181 state judges from 19 states who agreed to read a fictional case file and assign a sentence to an offender, ‘Jonathan Donahue,’ convicted of beating a restaurant manager senseless with the butt of a gun. All of the judges learned in their files that Mr. Donahue had been identified as a psychopath based on a standard interview — that is, he had a history of aggressive acts without showing empathy.

The case files distributed to the judges were identical, except that half included testimony from a scientist described as ‘a neurobiologist and renowned expert on the causes of psychopathy,’ who said that the defendant had inherited a gene linked to violent, aggressive behavior. This testimony described how the gene variant altered the development of brain areas that generate and manage emotion.

The account is an accurate description of one theory of how brain development may underlie aggressive behavior. Its applicability to any individual is unknown, however, given that many other factors could increase the likelihood of violence, researchers said.

The judges who read this testimony gave Mr. Donahue sentences that ranged from one to 41 years in prison, a number that varied with state guidelines. But the average was 13 years — a full year less than the average sentence issued by the judges who had not seen the testimony about genetics and the brain.”

Tags: Benedict Carey

The day after his brilliant October 30, 1938 War of the Worlds radio production caused widespread panic, Orson Welles sheepishly met with the press to explain his intentions. How could anyone ever fully trust the voice of authority again? Audio is mediocre.

Tags: Orson Welles

“In the 1910s deodorants and antiperspirants were relatively new inventions.” (Image by Terêza Tenório.)

I’ve sat next to a lot of you on the subway this summer, and I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that you smell like the outhouse behind a diarrhea factory. But things used to be even worse. The opening of Sarah Everts’ Smithsonian article about the birth of the underarm deodorant industry in stanky-assed America:

“Lucky for Edna Murphey, people attending an exposition in Atlantic City during the summer of 1912 got hot and sweaty.

For two years, the high school student from Cincinnati had been trying unsuccessfully to promote an antiperspirant that her father, a surgeon, had invented to keep his hands sweat-free in the operating room.

Murphey had tried her dad’s liquid antiperspirant in her armpits, discovered that it thwarted wetness and smell, named the antiperspirant Odorono (Odor? Oh No!) and decided to start a company.

But business didn’t go well—initially—for this young entrepreneur. Borrowing $150 from her grandfather, she rented an office workshop but then had to move the operation to her parents’ basement because her team of door-to-door saleswomen didn’t pull in enough revenue. Murphey approached drugstore retailers who either refused to stock the product or who returned the bottles of Odorono back, unsold.

In the 1910s deodorants and antiperspirants were relatively new inventions. The first deodorant, which kills odor-producing bacteria, was called Mum and had been trademarked in 1888, while the first antiperspirant, which thwarts both sweat-production and bacterial growth, was called Everdry and launched in 1903.

But many people—if they had even heard of the anti-sweat toiletries—thought they were unnecessary, unhealthy or both.”

••••••••••

Odo-Ro-No TV ad from 1960:

Tags: Edna Murphey, Sarah Everts

In case you missed Alex Stone’s smart NYT piece yesterday about the psychology of waiting on lines, here’s the opening:

“SOME years ago, executives at a Houston airport faced a troubling customer-relations issue. Passengers were lodging an inordinate number of complaints about the long waits at baggage claim. In response, the executives increased the number of baggage handlers working that shift. The plan worked: the average wait fell to eight minutes, well within industry benchmarks. But the complaints persisted.

Puzzled, the airport executives undertook a more careful, on-site analysis. They found that it took passengers a minute to walk from their arrival gates to baggage claim and seven more minutes to get their bags. Roughly 88 percent of their time, in other words, was spent standing around waiting for their bags.

So the airport decided on a new approach: instead of reducing wait times, it moved the arrival gates away from the main terminal and routed bags to the outermost carousel. Passengers now had to walk six times longer to get their bags. Complaints dropped to near zero.”

•••••••••••

Waiting on line in Akron for 23-cent pizza at Papa John’s, which is still four cents more than I would pay for it:

Tags: Alex Stone

Matt Ridley’s new Wired cover story, “Apocalypse Not,” reminds of the many endgames wrongly predicted over the past few decades for humanity, from post-peak oil to variants of flu to the hole in the ozone layer. It’s a wise piece, though we shouldn’t relax about doing things in a cleaner, more energy-conscious way. An excerpt:

“The threat to the ozone layer came next. In the 1970s scientists discovered a decline in the concentration of ozone over Antarctica during several springs, and the Armageddon megaphone was dusted off yet again. The blame was pinned on chlorofluorocarbons, used in refrigerators and aerosol cans, reacting with sunlight. The disappearance of frogs and an alleged rise of melanoma in people were both attributed to ozone depletion. So too was a supposed rash of blindness in animals: Al Gore wrote in 1992 about blind salmon and rabbits, while The New York Times reported ‘an increase in Twilight Zone-type reports of sheep and rabbits with cataracts’ in Patagonia. But all these accounts proved incorrect. The frogs were dying of a fungal disease spread by people; the sheep had viral pinkeye; the mortality rate from melanoma actually leveled off during the growth of the ozone hole; and as for the blind salmon and rabbits, they were never heard of again.

There was an international agreement to cease using CFCs by 1996. But the predicted recovery of the ozone layer never happened: The hole stopped growing before the ban took effect, then failed to shrink afterward. The ozone hole still grows every Antarctic spring, to roughly the same extent each year. Nobody quite knows why. Some scientists think it is simply taking longer than expected for the chemicals to disintegrate; a few believe that the cause of the hole was misdiagnosed in the first place. Either way, the ozone hole cannot yet be claimed as a looming catastrophe, let alone one averted by political action.”

Tags: Matt Ridley

Stanford’s driverless race car doing 120 mph. (Thanks Singularity Hub.)

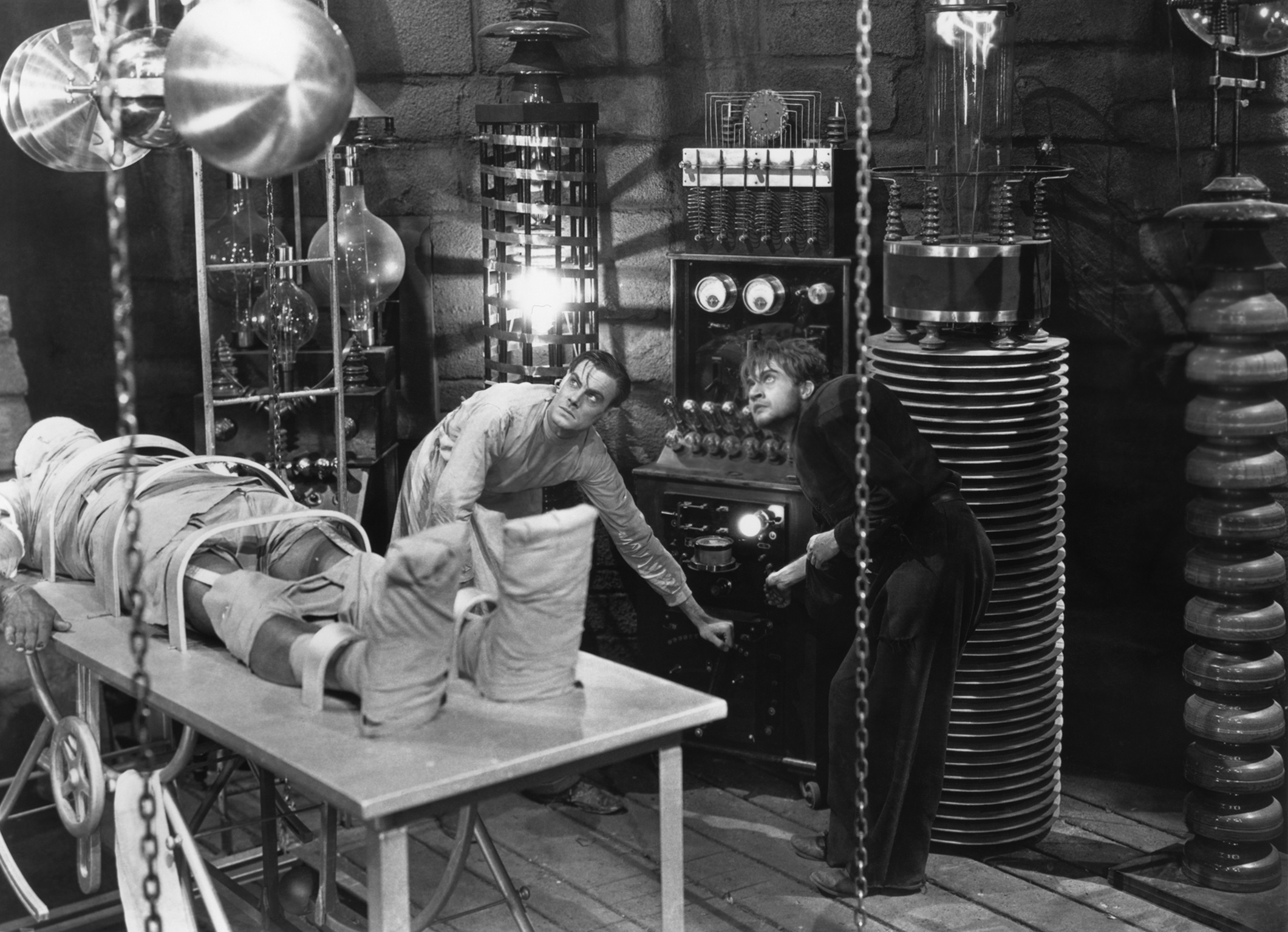

When I mentioned bio-hacking in the Stewart Brand post, it made me think of a very early article on the topic, Michael Schrage’s 1988 Washington Post piece “Playing God in Your Basement.” At the time, many experts thought that the genome might move rapidly into the mainstream in the way of the personal computer, which took about three decades to go from Homebrew Club to free wi-fi at Starbucks. But biopunk has remained a subculture rather than morphing into culture. So far, at least. An excerpt from Schrage’s writing:

“Personal computing began as a ‘homebrew’ hobby phenomenon with aspiring computerniks wiring up chips, toggle-switches and teletypes to produce desktop machines. Skeptics sneered that personal computers were a solution in search of a problem.

Now, several million unit sales later, the typewriter has become the do-do bird of word-processing, pimply-faced hackers can break into corporate data networks and yesterday’s cutting-edge computer is today’s paperweight.

‘The parallels to the microprocessor industry are there,’ says Lynn Klotz, formerly on the faculty of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Harvard and a director of BioTechnica International, a Cambridge, Mass., recombinant DNA firm. ‘Both are characterized by general ease and use of declining costs.’

‘As a body, the biotechnology industry is not unlike where the computer industry was in 1975,’ says sociologist Everett Rogers, a University of Southern California professor who has conducted extensive research into the diffusion of innovation. ‘There’s a lot of uncertainty, a lot of rapid innovation and no single main consumer product.’

Rogers points out that hackers–a technology subculture he studied while at Stanford–were attracted to computers as a medium ‘where they could express themselves in an artistic way.’ A number of computer hackers did indeed win science fairs either with hardware or software they created. With the insistent diffusion of biotechnology, Rogers believes, a technology subculture could grow around DNA just as one did for silicon and software.

He wryly notes that when the news media discovered computer hackers, ‘people went into a state of alarm. There were movies about hackers. Perhaps in a few years there will be movies about (bio-hackers) creating Frankensteinian monsters.'”

Tags: Everett Rogers, Lynn Klotz, Michael Schrage

I don’t think the folding car is the wave of the future unless the Chinese government insists (by fiat) that it will be. But the Hiriko Fold is upon us regardless. From the Daily Mail:

“City dwellers know the most difficult part of urban driving isn’t the mental minicab drivers or suicidal cyclists, but finding a space to park the car once you have safely arrived at your destination.

But now a solution is at hand in the form of a revolutionary new car that can actually fold up to fit itself into the tiniest of gaps.

Researchers from MIT’s Changing Places group, working in collaboration with the Spanish Basque region’s development agency DENOKINN have developed the Hiriko Fold, a convenient, eco-friendly car for city commuting.”

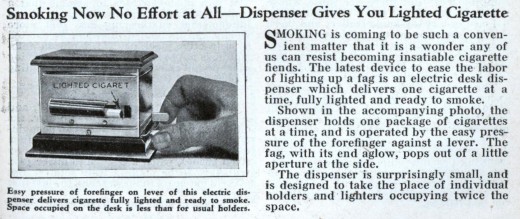

From the excellent Retronaut blog, a brief 1931 Modern Mechanix article about a lit-cigarette dispenser.

Horrible deaths bother us more than the mundane kind. It doesn’t make sense since dead is dead, but the narratives around a demise have meaning for us. We try to separate deaths into those that are “needless” and those that “understandable.” Some just upset us or excite us more in a lurid way than others.

When a helicopter crashes and two or three people die in NYC, the tragedy gets nonstop news coverage. A car accident the same day that results in four deaths gets a couple of minutes at most. It’s the greater lack of control that bothers us, the plunging from the sky. A truck accident in Texas that happened soon after the Aurora shooting tragedy killed nearly as many people but received only scant national attention. The families of those lost in the highway accident are just as devastated, but an automobile accident is something we can process, while a movie theater being shot up intentionally for no reason is not. It’s just more terrible.

These feelings of dread and horror don’t only affect us in a visceral way but can shape policy. In a WSJ piece, Richard Muller, who recently quit his stance as a climate-change denier, argues that our fear of nuclear-power accidents, even in wake of Fukushima, is overstated. That may be true, though it doesn’t seem like nukes should be the focus of our sustainable-energy quest going forward. From his article:

“The tsunami that hit Japan in March 2011 was horrendous. Over 15,000 people were killed by the giant wave itself. The economic consequences of the reactor destruction were massive. The human consequences, in terms of death and evacuation, were also large. But the radiation deaths will likely be a number so small, compared with the tsunami deaths, that they should not be a central consideration in policy decisions.

The reactor at Fukushima wasn’t designed to withstand a 9.0 earthquake or a 50-foot tsunami. Surrounding land was contaminated, and it will take years to recover. But it is remarkable how small the nuclear damage is compared with that of the earthquake and tsunami. The backup systems of the nuclear reactors in Japan (and in the U.S.) should be bolstered to make sure this never happens again. We should always learn from tragedy. But should the Fukushima accident be used as a reason for putting an end to nuclear power?

Nothing can be made absolutely safe. Must we design nuclear reactors to withstand everything imaginable? What about an asteroid or comet impact? Or a nuclear war? No, of course not; the damage from the asteroid or the war would far exceed the tiny added damage from the radioactivity released by a damaged nuclear power plant.”

Tags: Richard Muller

Robots can handle driving and assembly-line work better than we can, with far less error and far more accuracy, no doubt. The question, beyond the loss of manufacturing jobs, is whether these tasks, once roboticized, can be hacked to cause mass mishaps. Will 10,000 drivers simultaneously be forced to turn left instead of right? Can terrorists cause a defect in plane parts so that they’ll be prone to crash? I would guess there’s enough quality control to avoid the latter, but the former seems plausible. From “Skilled Work, Without the Worker,” by John Markhoff in the New York Times:

“This is the future. A new wave of robots, far more adept than those now commonly used by automakers and other heavy manufacturers, are replacing workers around the world in both manufacturing and distribution. Factories like the one here in the Netherlands are a striking counterpoint to those used by Apple and other consumer electronics giants, which employ hundreds of thousands of low-skilled workers.

‘With these machines, we can make any consumer device in the world,’ said Binne Visser, an electrical engineer who manages the Philips assembly line in Drachten.”

Tags: Binne Visser, John Markhoff

The rise of the machines is, unsurprisingly, extending further and further into space. From “The Astronaut Question,” by James R. Chiles in Air & Space magazine, a section drawing a parallel between driverless cars and automated space flight:

“When comparing spacecraft-driving to car-driving, one more analogy is needed: the automated, driverless car. During the 2010 VisLab Intercontinental Autonomous Challenge, four electric automatic automobiles got themselves from Italy to China. After more than a quarter-million miles on the road, Google’s Self-Driving Car now has a license to roam Nevada, albeit with an engineer behind the wheel, who, says Google, hardly ever needs to take control.

The next wave of manned orbital craft now being built promise to be equally automated when flown. Like the H-2, the Dragon spacecraft from SpaceX will park within arm’s length of the station. On a routine, no-glitches mission in which Boeing’s CST-100 flies to the ISS, the astronauts will leave all the driving to robots, which will use a navigation system evolved from Orbital Express, its unmanned satellite-rendezvous mission for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. In that 2007 experiment, one satellite intelligently chased down another, latched on, and exchanged fuel and components, all without human control.”

Tags: James R. Chiles

A cool old-school commercial for Olivetti, which was making computers with a great flair for design long before Apple.

Tags: Camillo Olivetti