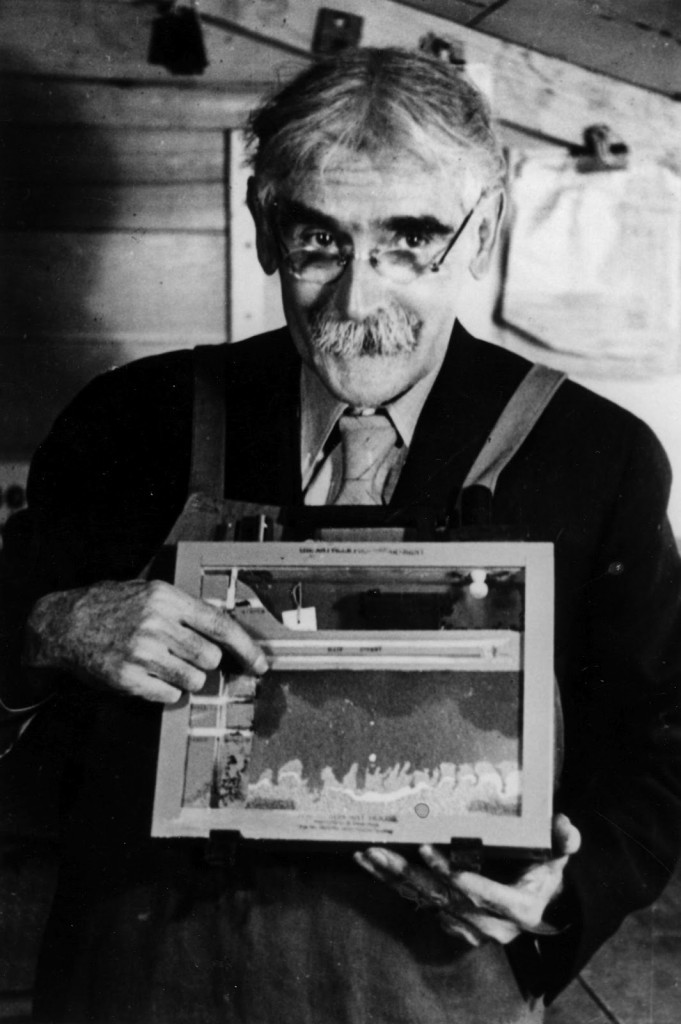

This classic photograph profiles late-life Mary Baker Eddy, who was the founder of the hokum known as Christian Science, a scripture-based faith healing that believed medicine and hygiene were unnecessary. She was born in 1812 in New Hampshire, began “hearing voices” in her girlhood, and was soon known for her ability to “cure” animals and people alike. Her talent and charisma and persistence allowed her to remarkably create an international cult in an age long before mass media. Even her detractors were awed by her unlikely empire. In an otherwise lacerating 1903 critique of Mrs. Eddy, Mark Twain wrote: “She is interesting enough without an amicable agreement. In several ways she is the most interesting woman that ever lived, and the most extraordinary. The same may be said of her career, and the same may be said of its chief result. She started from nothing. Her enemies charge that she surreptitiously took from Quimby a peculiar system of healing which was mind-cure with a Biblical basis. She and her friends deny that she took anything from him. This is a matter which we can discuss by-and-by. Whether she took it or invented it, it was—materially—a sawdust mine when she got it, and she has turned it into a Klondike.”

Eddy became a shadowy figure in her later years–was she a morphine addict as rumors suggested? was she mentally unfit to care for herself?–though it didn’t diminish her hold on the public’s attention. She died on December 3, 1910. A passage about the origins of her calling from an article about her two days later in the New York Times:

“Some of her friendly biographers quote Mrs. Eddy as having said in describing the discovery of her so-called psychological sense:

When I was very little I used to hear voices. They called me. They spoke my name. ‘Mary! Mary!’ I used to go to my mother and say, ‘Mother did you call me? What do you want?’ and she would say ‘No, my child, I didn’t call you.’ Then I would go away and play but the voices would call me again distinctly.

There was a day when my cousin, whom I dearly loved. was playing with me, and she too heard the voices. She said: ‘You’re mother’s calling you, Mary,’ and when I didn’t go I could hear them again. But I knew that it wasn’t mother. My cousin didn’t know what to make of my behavior, because I was always an obedient child. ‘Why, Mary,’ she repeated, ‘what do you mean by not going?’

When she heard the voices again she went to my mother, and my cousin said:

‘Didn’t you call Mary?’ My mother asked if I heard voices and I said I did. Then she asked my cousin if she heard them, and when she said ‘Yes,’ my mother cried.

She talked with me that night and told me, when I heard them again–no matter where I was-to say: ‘What wouldst Thou, Lord? Here I am.’ That is what Samuel said, you know, when the Lord called him. She told me not to be afraid, but to surely answer.

The next day I heard voices again, but was too frightened to speak. I felt badly. Mother noticed it and asked me if I had heard the call again. When I said that I was too frightened to say what she had told me she talked with me and told me that the next time I must surely answer and not fear.

When the voice came again I was in bed. I answered as quickly as I could, as she had told me to do, and when I had spoken a curious lightness came over me. I remember it so well! It seemed to me I was being lifted off my little bed, and I put out my hands and caught the sides. From that time I never heard the voices. They ceased.”