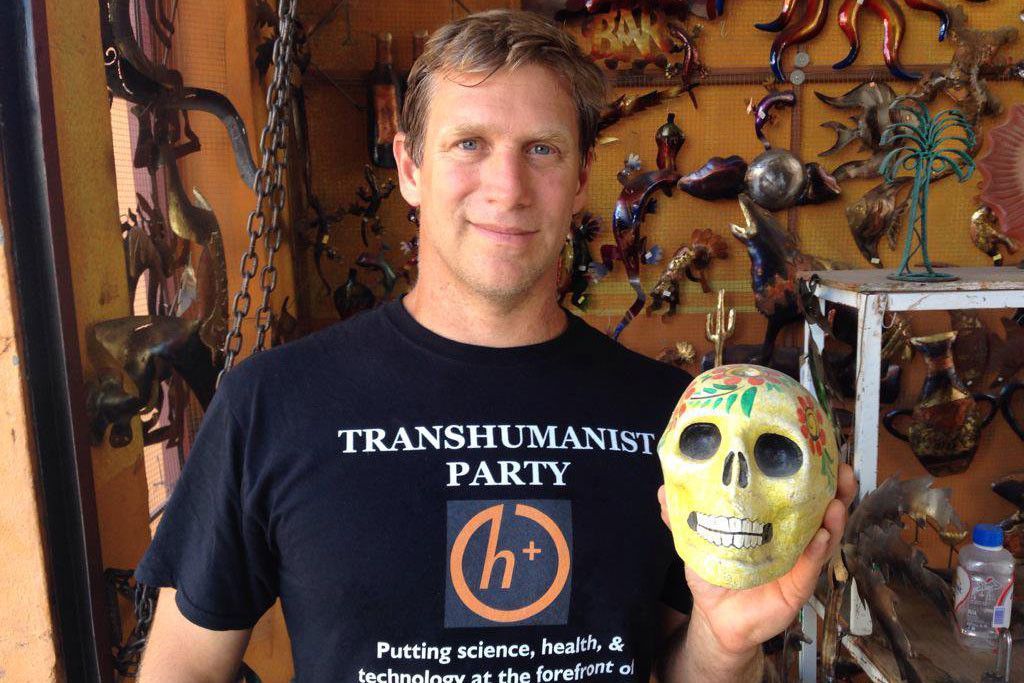

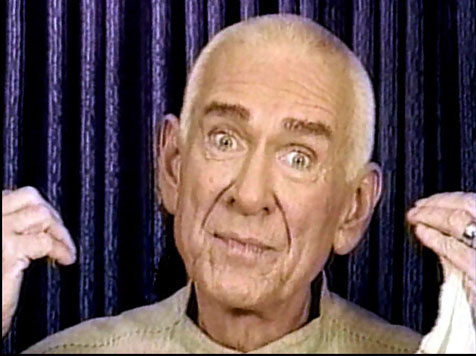

Because Gary Johnson smokes pot and clearly doesn’t bother studying for tests, the Libertarian Presidential candidate has been sort of the cool kid of the class this election season. But Zoltan Istvan, standard-bearer of the Transhumanist Party, is not only in favor of legalizing all drugs in America, he also believes athletes should be on PEDs and we needn’t regulate gene editing. Now that man’s a party!

I’ve really enjoyed writing about Istvan’s ideas over the course of his campaign, even if I’m sometimes aghast at them. The unorthodox pol just did a lively pre-Election Day Ask Me Anything at Reddit, and I’ve embedded a few exchanges below.

Question:

Is there a way to protect privacy with technology developing along current trajectory? Big data and more deliberate forms of mass surveillance seem to suggest major social changes concerning and individual’s right to keep secrets.

Will privacy become an anachronism in the next few decades?

Zoltan Istvan:

Everyone hates this, but we must get over our privacy issues. They simply won’t survive the onslaught of tech. My response is to observe the government as much as they want to observe us, so at least it’s a two-way street. Ultimately, though, there’s just too much tech tracking us now and 20 years into the future for privacy to survive as we know it today.

Question:

Do you think the claim by a few people that we’ve subverted our natural evolution in favour of becoming a part of a singularity has any kind of credence? What kind of obstacles do you think we still have to overcome for that kind of scenario to be a positive experience?

Zoltan Istvan:

It’s tough to talk about the Singularity since the idea is essentially beyond our comprehension. It’s such a bizarre concept, and yet I believe in it. But we are certainly are subverting our natural evolution, and to those that oppose it, I like to bring up the fact that without basic evolutionary progress, we might still be dying from infections from cavities.

Question:

Very good point. So does that mean you tend to believe that we’re more likely to find ways to augment and prolong through methods like, say, nano technology as opposed to shedding physical form entirely?

Zoltan Istvan:

Yes, I think we’ll likely want to stay in semi-human form for as long as possible. Even I’m a bit skeptical to just become intelligent AI or organized star dust.

Question:

I believe this to be a long-term solution to technological unemployment that doesn’t involve a huge centralized government agency, but I’ve also come to consider how Basic Income might be useful towards attaining this system. However, I’ve been cautioning against total reliance on this idea, because I realize that almost all governments out there are only out to perpetuate power, and a basic income in a highly automated society represents a great deal of power over citizens who will have no other way to survive besides this common dole.

So my questions are thus:

A. What are your plans involving basic income?

B. Do you believe that Basic Income by itself is enough, or that Vyrdism represents a proper step forward beyond it?

C. Are you concerned by the potential ability of governments to abuse the concept of basic income to enforce a totalitarian order?

Zoltan Istvan:

I highly support a basic income. I can’t see any other way around the situation that is not completely dystopic for the future. I have a plan over 6 years to begin implementing a moderate basic income, which would include higher taxes, companies that create the automation to pay up, and loaning or selling of federal land (we have tons available). With that, we could bridge a few decades of a UBI. After that, it’s anyone’s guess what will happen. But capitalism likely won’t survive.

This article of mine is one possibility of an outcome. The lack of any ownership might prevent a totalitarian order. Read here.

Question:

| and loaning or selling of federal land (we have tons available.

Are you talking about national parks? Would you sell them to entities that will function as a park/nature reserve only or would you allow them to mine or drill for natural resources?

Zoltan Istvan:

National Parks would be last on the list to touch. But there’s plenty of other land just sitting out there. And yes, I’d allow some natural resources to be mined or drilled. But very selectively. We all must take a step back and imagine how many trillions of dollars we’re dealing with here. Half the 11 Western most states are federal land. And our population is barely budging, and the machine age is upon us. I doubt there will be more than a few more human generations behind us anymore. So the land is not as necessary as it once was. We simply might not be entities that eat anymore in 50-100 years. So let’s use that federal land to make our lives better now.

Question:

Hey Zolt. Wondering if you can talk a little bit about your thoughts on regulating human enhancement through gene editing methods such as CRISPR. I know as a libertarian-leaning person, you are against agency regulation in general, however, do you feel there is a place for a regulatory agency outside or parallel to the FDA to oversee safety and efficacy of human enhancement and germline modification? Thanks!

Zoltan Istvan:

On this, I just really don’t think we need regulation. I think the greater concern is that China goes full speed ahead with genetic editing and America gets left behind and we dance around whether it’s a good idea–and then shortly after a new generation of Chinese babies are born with better genetic intelligence than everyone else (posing a serious national security and cultural issue). I say embrace it. We don’t need a new agency for gene editing.

Question:

Where do Sports fall into the Transhumanist viewpoint?

Zoltan Istvan:

I think sports are great when we allow ourselves to use drugs and enhancements. I think the future is the creation of new sports with new technologies, and turning humans sports more into Formula 1 type racing endeavors, where the scientists and engineers and coaches are just as important as the athletes. Read here.

Question:

If the world becomes globalized through tech, can we expect countries to dissolve? Will the world become borderless?

Zoltan Istvan:

Yes, I don’t expect as many countries in 25 years. And in 50, there might only be a few left. Despite BREXIT, I still think we will go borderless at some point. I advocate for this in the future. I think peace will come of it.

Question:

Are you voting for yourself in a week, or for one of the other candidates?

Zoltan Istvan:

I’m voting for myself. I will totally understand given all the circumstances if my supporters vote for others though.

Question:

Would you endorse one of the other candidates over the other?

Zoltan Istvan:

Yes, in general, I think in swing states, you should vote for Hillary (though I’m not anti-Trump, I just like Hillary better). In Utah, vote Evan McMullin. Everywhere, else I suggest voting for Gary Johnson. If Gary get’s 5% of the vote, the Libertarian Party will get federal funding. That means America will not longer be a 2-party system. Whether you like Libertarians is not the question–it’s a question of overcoming the two party monopoly, which I think is important for democracy.

Question:

How do you justify telling people to vote for Hillary though?

I mean she represents everything that people hate about the government right now. From her directly lying to the public and holding no remorse about it, to her husband pardoning criminals on the way out for money, to being under active FBI investigation for deleting evidence after a subpoena

Zoltan Istvan:

One main reason is that is Trump becomes President, and gets assassinated, Mike Pence will take office and that could be a disaster for science and tech, especially in the gene editing and AI era. Read my sci-fi story.

I like Gary Johnson the best. Actually, I like myself the best, but the reality is the choice is between Hillary and Trump. And people must make that choice.•