Garry Kasparov’s defeat at the hands–well, not exactly hands–of Deep Blue was supposed to have delivered a message to humans that we needed to dedicate ourselves to other things–but the coup de grace was ignored. In fact, computers have only enhanced our chess acumen, making it clear that thus far a hybrid is better than either carbon or silicon alone. In the wake of Computer Age child Magnus Carlsen becoming the greatest human player on Earth, Christopher Chabris and David Goodman of the Wall Street Journal look at the surprising resilience of chess in these digital times. The opening:

“In the world chess championship match that ended Friday in India, Norway’s Magnus Carlsen, the cool, charismatic 22-year-old challenger and the highest-rated player in chess history, defeated local hero Viswanathan Anand, the 43-year-old champion. Mr. Carlsen’s winning score of three wins and seven draws will cement his place among the game’s all-time greats. But his success also illustrates a paradoxical development: Chess-playing computers, far from revealing the limits of human ability, have actually pushed it to new heights.

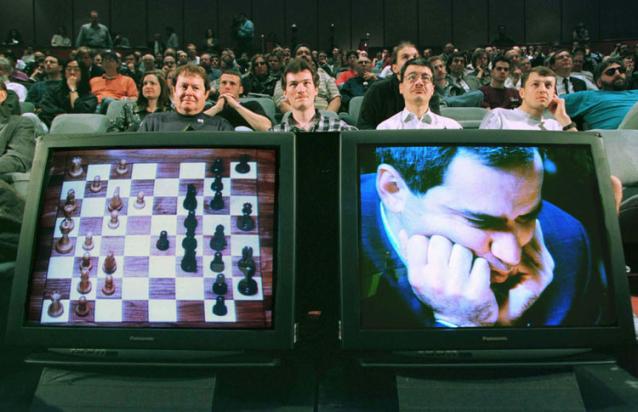

The last chess match to get as much publicity as Mr. Carlsen’s triumph was the 1997 contest between then-champion Garry Kasparov and International Business Machines Corp.’s Deep Blue computer in New York City. Some observers saw that battle as a historic test for human intelligence. The outcome could be seen as an ‘early indication of how well our species might maintain its identity, let alone its superiority, in the years and centuries to come,’ wrote Steven Levy in a Newsweek cover story titled ‘The Brain’s Last Stand.’

But after Mr. Kasparov lost to Deep Blue in dramatic fashion, a funny thing happened: nothing.”•

_________________________________________

“In Norway, you’ve got two big sports–chess and sadness”: