We tend to choose the devil we know.

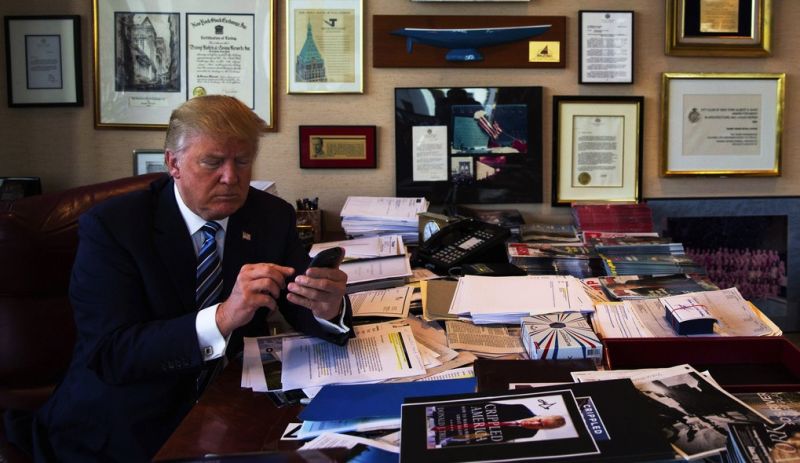

In this election, Americans opted for the past, something that never quite reappears, voting for a nostalgic vision of postwar labor, when manufacturing provided steady, secure middle-class livings. The problem is, factory jobs aren’t really returning regardless of who’s President since these positions are being rapidly thinned by automation, even when companies reshore their plants, and those positions yet to be assumed by machines aren’t what they used to be, as former unionized slots are now often contracted, temporary, poorly paid and dangerous.

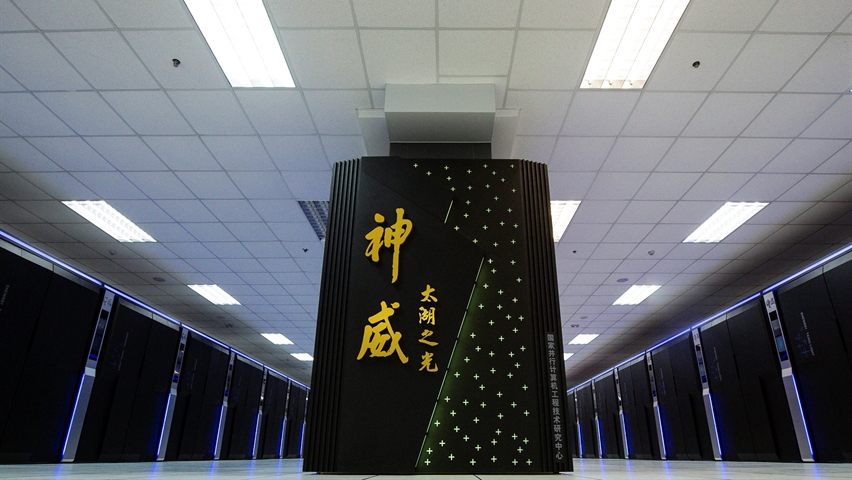

Needless to say, manufacturing is not the future anymore than coal is, and while we dream on these remnants of the Industrialized Age, we fall behind China and others in areas that could provide a decent tomorrow, alternative energies among them. It’s an unforced error by the U.S. that we’ll have to endure.

Excerpts follow from: 1) Gary Silverman’s excellent Financial Times article on the perils of manufacturing work no longer guided by “industrial paternalism,” and 2) Lauren Weber’s eye-opening WSJ report on the disquieting shift to contracted labor.

From Silverman:

Regina Elsea of Chambers County, Alabama, had her work cut out for her. At the age of 20, she was engaged to be married and had bills to pay — for her new car, the home she rented with her fiancé, the toys she liked to buy for her dog Cow and, if all went according to plan, the wedding of her dreams, complete with a $4,000 white dress that fitted just right. So, she took a job in a factory last year.

Elsea had the option because Chambers County has been enjoying a manufacturing revival. A hardscrabble corner of the southern US with 34,000 residents, its economy was hurt badly by the decline of its textile industry early this century. However, local officials offering tax breaks and other aid remade the county into a supply-chain link for South Korean carmakers. New factories arose to provide just-in-time parts for two nearby assembly plants— Hyundai in Montgomery, Alabama, and Kia in West Point, Georgia.

As a result, unemployment in Chambers County fell from 19.4 per cent in February 2009 to 5.5 per cent last year. But the conditions Elsea encountered on her highly automated production line were a far cry from the ones that people were dreaming about at the Donald Trump campaign rallies. Elsea found work as a temporary employee — she was paid $8.50 an hour, according to her family — and the work killed her.

On June 18 2016 — a Saturday — a robot that Elsea was overseeing at the Ajin USA auto parts plant in Cusseta, Alabama, stopped moving. She and three colleagues tried to get it going, stepping inside the cage designed to protect workers from the machine, according to the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration. When the robot restarted abruptly, Elsea was crushed. She died the next day when she was taken off a life-support machine, with her mother, Angel Ogle, at her side. After an investigation, Osha concluded that the accident that killed Elsea was preventable.

“Everybody needs to know what’s going on in those plants,” says Ms Ogle, 43, a housecleaner who once worked for a Korean auto parts maker in Alabama herself. “I have seen too many people get hurt.”

The life and death of Regina Elsea points to a national predicament as President Trump seeks to “make America great again” by increasing industrial employment. With automation on the rise and unionisation on the decline, manufacturing jobs no longer guarantee a secure middle-class life as they often did in the past. Much of the new work is low paid and temporary. Staffing agencies sometimes supply factories with workers who have little training or experience — and who can quickly find themselves in harm’s way.•

From Weber:

No one in the airline industry comes close to Virgin America Inc. on a measurement of efficiency called revenue per employee. That’s because baggage delivery, heavy maintenance, reservations, catering and many other jobs aren’t done by employees. Virgin America uses contractors.

“We will outsource every job that we can that is not customer-facing,” David Cush, the airline’s chief executive, told investors last March. In April, he helped sell Virgin America to Alaska Air Group Inc. for $2.6 billion, more than double its value in late 2014. He left when the takeover was completed in December.

Never before have American companies tried so hard to employ so few people. The outsourcing wave that moved apparel-making jobs to China and call-center operations to India is now just as likely to happen inside companies across the U.S. and in almost every industry. …

The shift is radically altering what it means to be a company and a worker. More flexibility for companies to shrink the size of their employee base, pay and benefits means less job security for workers. Rising from the mailroom to a corner office is harder now that outsourced jobs are no longer part of the workforce from which star performers are promoted.

For companies, the biggest allure of replacing employees with contract workers is more control over costs. Contractors help businesses keep their full-time, in-house staffing lean and flexible enough to adapt to new ideas or changes in demand.

For workers, the changes often lead to lower pay and make it surprisingly hard to answer the simple question “Where do you work?” Some economists say the parallel workforce created by the rise of contracting is helping to fuel income inequality between people who do the same jobs.•