Mass media was supposed to use facts to shine a cleansing light, but that supposes a uniform noble impulse on the part of those sending out the signals. In this way, humans and communications technology are a mismatch.

Mass media was supposed to use facts to shine a cleansing light, but that supposes a uniform noble impulse on the part of those sending out the signals. In this way, humans and communications technology are a mismatch.

· · ·

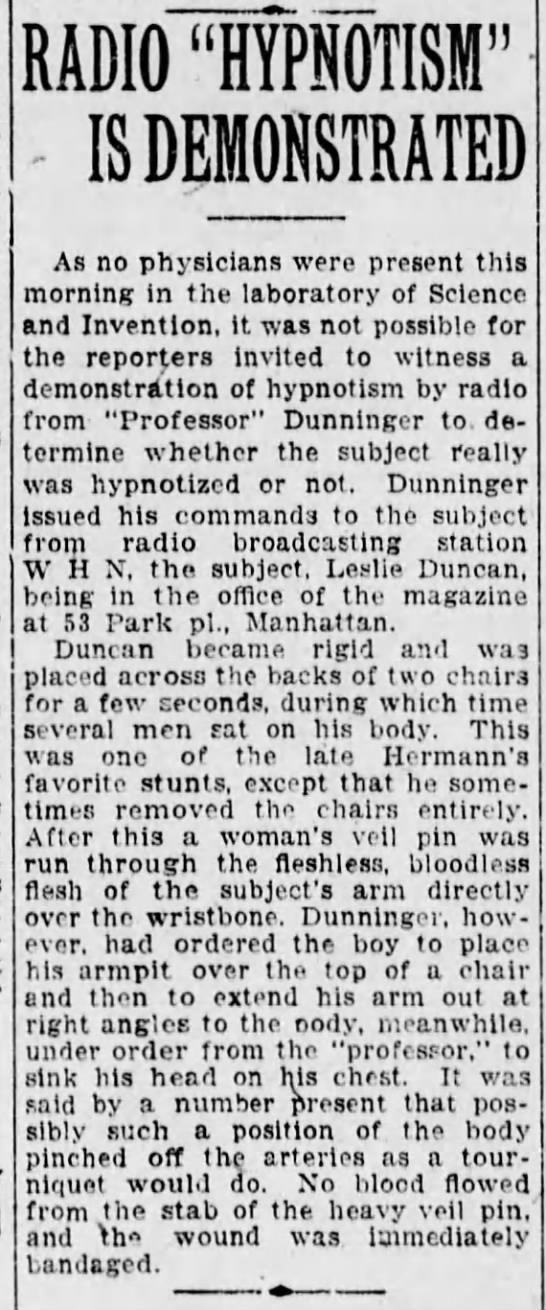

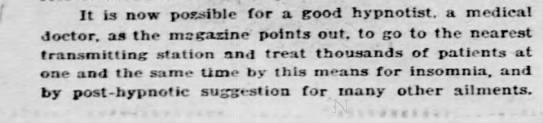

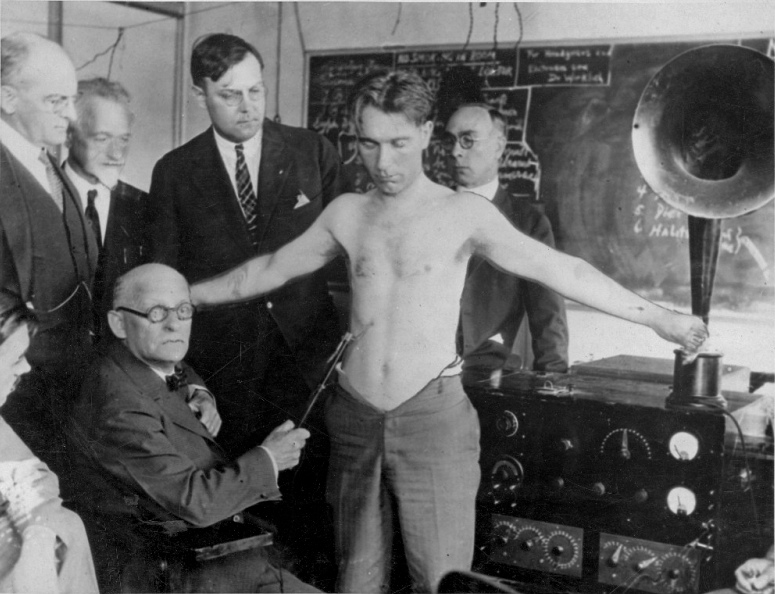

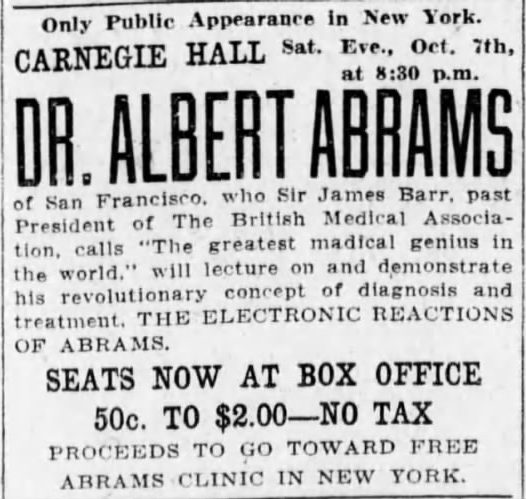

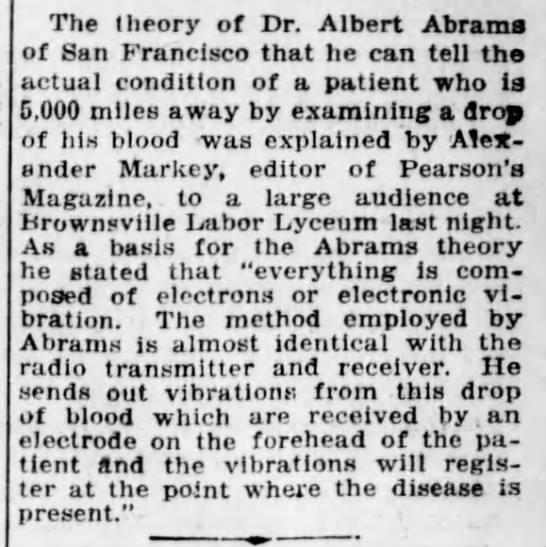

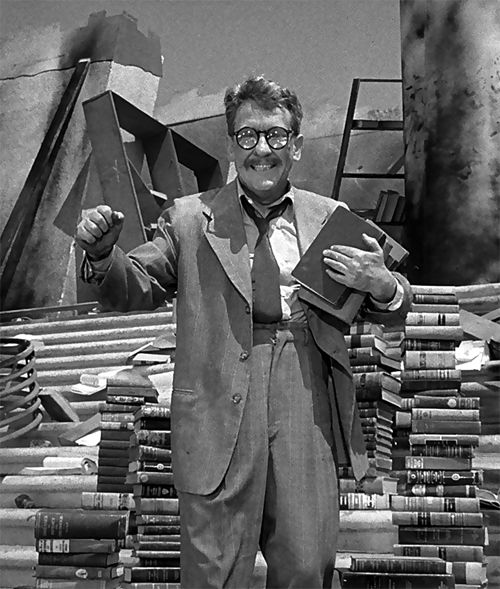

In 1923, “Professor” Joseph Dunninger, the mesmerist, demonstrated the art of “radio hypnotism,” boasting that his disembodied voice could influence the behavior of those remote to him.

It was soon hailed that hypnotists would be able to simultaneously cure chronic alcoholics and other troubled citizens by the thousands thanks to the growing popularity of the medium.

It was ridiculous, of course, if you considered the scenario literally.

· · ·

D.W. Griffith, another sort of mesmerist, had Dunninger beaten by eight years. His deeply racist 1915 epic, Birth of a Nation, was a staple of American theaters for a decade and spent the pre-Talkie period as the standard by which all other films were measured, while also igniting a vast revival of the Ku Klux Klan. From Adam Hochschild in the New York Review of Books:

The KKK’s rebirth was spurred by D.W. Griffith’s landmark 1915 film, Birth of a Nation. The most expensive and widely seen motion picture that had yet been made, it featured rampaging mobs of newly freed slaves in the post–Civil War South colluding with rapacious northern carpetbaggers. To the rescue comes the Ku Klux Klan, whose armed and mounted heroes lynch a black villain, save the honor of southern womanhood, and prevent the ominous prospect of blacks at the ballot box. “It is like teaching history with lightning,” said an admiring President Woodrow Wilson, an ardent segregationist, who saw the film in the White House.•

Make no mistake: As surely as the Lost Cause, this movie meant to inculcate. As one newspaper wrote in the year of the moving picture’s release: “That parents regard the picture as educating and one their children see is evidenced by hundreds of parents who go with their young people to performances, especially in the afternoon.” That would ultimately prove an underestimation by millions, as no movie in the early part of the 20th century would be attended so rabidly and “educate” so many Americans.

· · ·

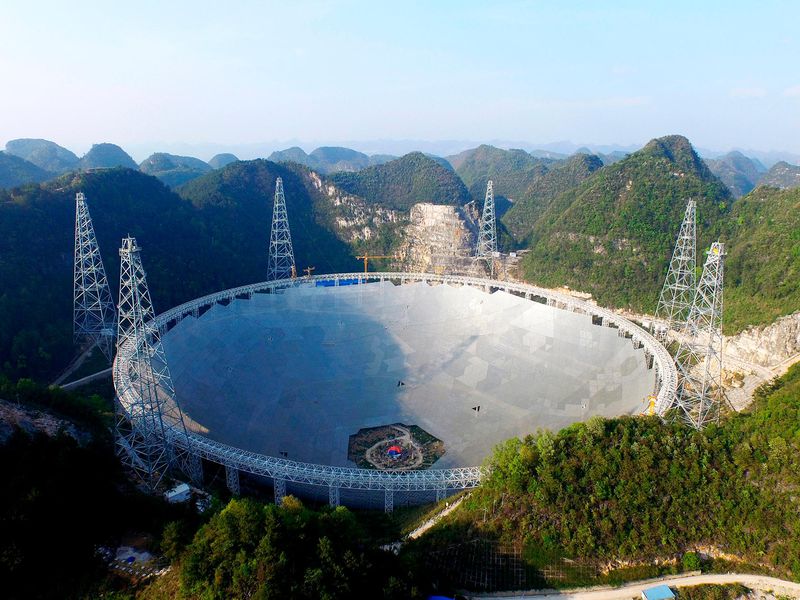

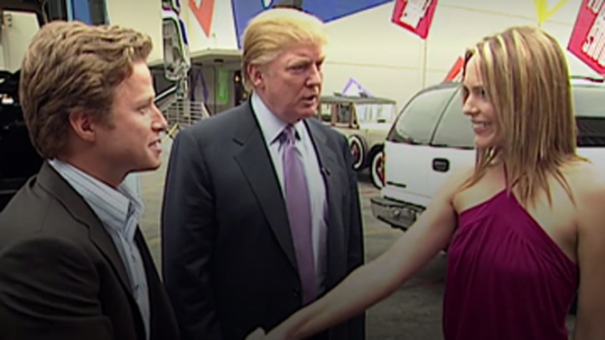

Social networks today use their lightning to not only teach history but also current events, a topic that’s become riddled with “alternate facts,” a process pushed on purpose by Trump and his minions and buttressed by online Russian interlopers, actual and virtual. It’s a distortion machine on a massive scale and thus far it’s worked well enough to tip the balance. This new connectedness that midwifed the Arab Spring has also given birth to a Russian winter, and the chill is being felt all over the world.

· · ·

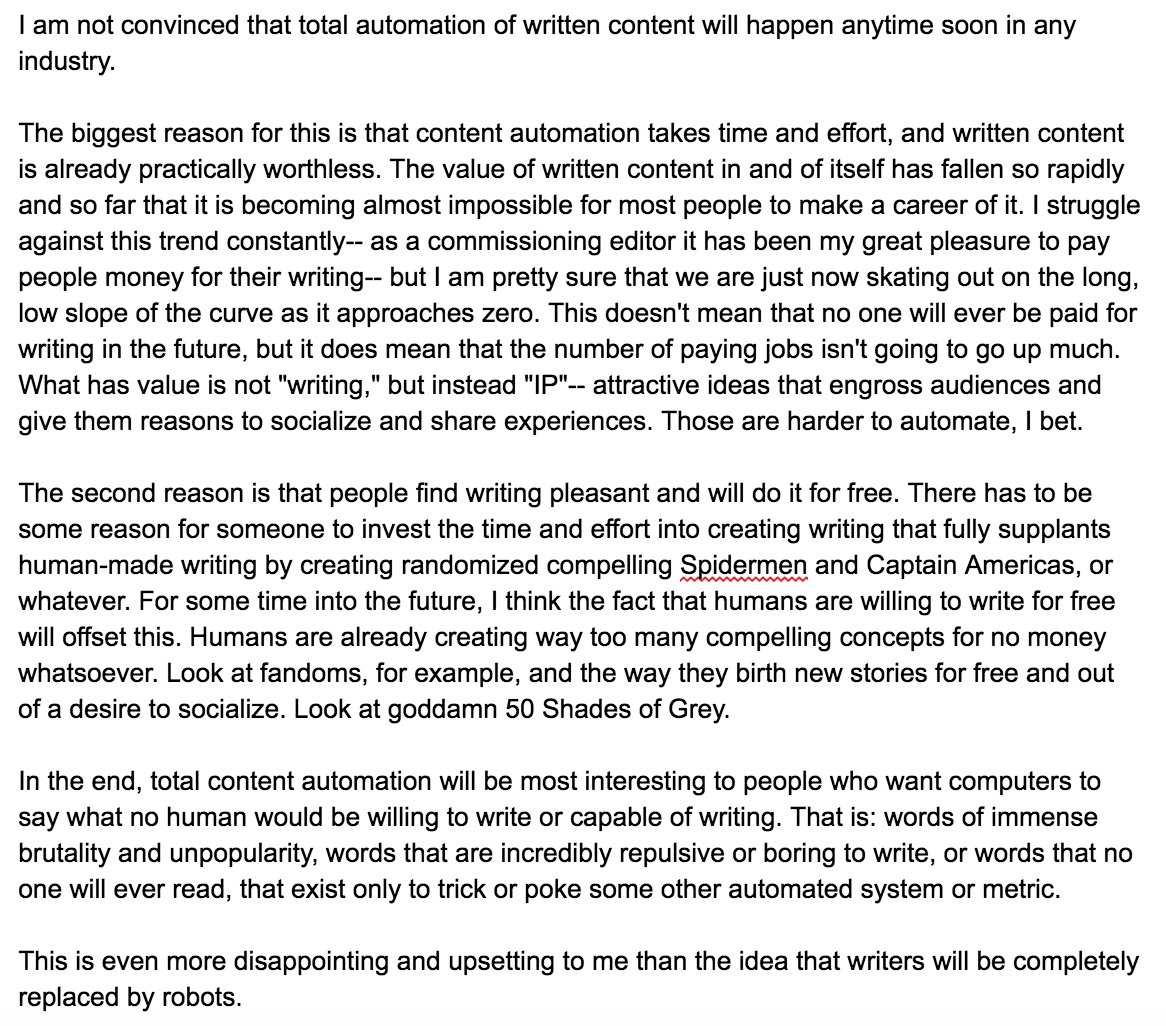

Facebook has made a few public-relation concessions and a few hires in the aftermath of the angry blowback for its big role in allowing our Presidential election to be impacted by the Kemlin, but the company clearly lacks the will if not the ability to stem the bleeding. There’s a financial reason for its failing to reject Fake News: According to Sam Levin’s Guardian piece, “a Facebook spokesperson said that once an article had been labeled as false, its future ‘impressions’ dropped by 80%.”

The opening:

Journalists working for Facebook say the social media site’s fact-checking tools have largely failed and that the company has exploited their labor for a PR campaign.

Several fact checkers who work for independent news organizations and partner with Facebook told the Guardian that they feared their relationships with the technology corporation, some of which are paid, have created a conflict of interest, making it harder for the news outlets to scrutinize and criticize Facebook’s role in spreading misinformation.

The reporters also lamented that Facebook had refused to disclose data on its efforts to stop the dissemination of fake news. The journalists are speaking out one year after the company launched the collaboration in response to outrage over revelations that social media platforms had widely promoted fake news and propaganda during the US presidential election.

Facebook has since revealed that it facilitated Russia’s efforts to interfere with US politics, allowing divisive political ads and propaganda that reached 126 million Americans.

“I don’t feel like it’s working at all. The fake information is still going viral and spreading rapidly,” said one journalist who does fact-checks for Facebook and, like others interviewed for this piece, was not authorized to speak publicly due to the continuing partnership with the company. “It’s really difficult to hold [Facebook] accountable. They think of us as doing their work for them. They have a big problem, and they are leaning on other organizations to clean up after them.”

Facebook announced to much hype last December that it was partnering with third-party factcheckers – including the Associated Press, Snopes, ABC News, PolitiFact and FactCheck.org – to publicly flag fake news so that a “disputed” tag would warn users about sharing debunked content. A Guardian review this year found that the fact-checks seemed to be mostly ineffective and that “disputed” tags weren’t working as intended.

Now, some of the factcheckers are raising concerns, saying the lack of internal statistics on their work has hindered the project and that it is unclear if the corporation is taking the spread of propaganda seriously.•