I was critical of Bill Gates’ recent suggestion that America utilize taxation to slow down progress in robotics. First of all, defining “robot” isn’t so simple. Are they only machines that move across warehouse floors? Are they algorithms? Will they be something else entirely tomorrow?

Also there’s no central switch that can be pointed at OFF until everything makes sense. The race in machine intelligence among states will see the actions of some players influence priorities and ethics across borders. No wall will keep out the future.

In “Learning to Love Intelligent Machines,” a WSJ essay taken from his book Deep Thinking: Where Artificial Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins, Garry Kasparov, the Digital Age John Henry, argues that AI will bring a bounty, not a threat. I agree with the former contention but not the latter.

John Henry’s postscript: He won, but he died. In the aftermath, steam and gas and electricity made us richer as they transformed society, but they also imperiled us with their deleterious impact on the environment. Long after we learned the damage the carbon was doing, it’s proven difficult politically and financially to alter the course and unplug the machine.

Garry Kasparov’s postscript: He lost, but he survived, and perhaps he, and the rest of us, will thrive because of increasingly intelligent machines. Aspects of life will improve, some markedly, as machines progress, but these stronger tools will also make for greater potential dangers: nonstop surveillance, disruption to democracy, complete loss of privacy, cascading disaster, etc. There will be no turning off this machine once we’re fully lowered into it, and that will be soon.

We may not be able to avoid extinction as a species in the long run without super-algorithms, but they will also be their own existential risk.

Kasparov is right, however, in saying: “There is no going back, only forward.”

The opening:

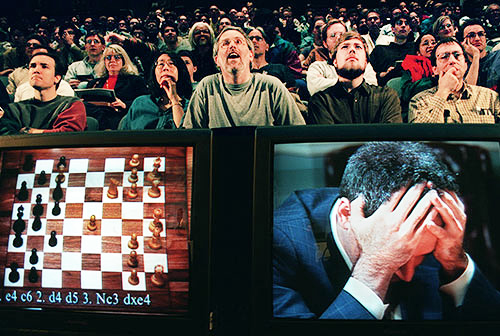

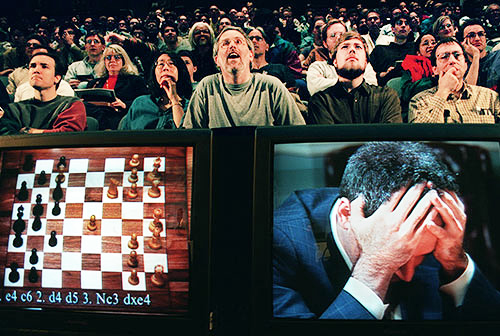

It was my blessing and my curse to be the world chess champion when computers finally reached a world championship level of play. When I resigned the final match game against the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue on May 11, 1997, I became the first world champion to be defeated in a classical match by a machine.

It is no secret that I hate losing, and I did not take it well. But losing to a computer wasn’t as harsh a blow to me as many at the time thought it was for humanity as a whole. The cover of Newsweek called the match “The Brain’s Last Stand.” Those six games in 1997 gave a dark cast to the narrative of “man versus machine” in the digital age, much as the legend of John Henry did for the era of steam and steel.

But it’s possible to draw a very different lesson from my encounter with Deep Blue. Twenty years later, after learning much more about the subject, I am convinced that we must stop seeing intelligent machines as our rivals. Disruptive as they may be, they are not a threat to humankind but a great boon, providing us with endless opportunities to extend our capabilities and improve our lives.•

In his WSJ article, Kasparov writes that by the 1980s, people knew machines would soon be kings of chess. He was most certainly not among that enlightened set.

He defeated Deep Thought in 1989 and believed a computer could never best him. But by 1997 Deep Blue turned him–and humanity–into an also-ran in some key ways. The chess master couldn’t believe it at first–he assumed his opponent was manipulated by humans behind the scene, like the Mechanical Turk, the faux chess-playing machine from the 18th century. But no sleight of hand was needed.

Below are the openings of three Bruce Weber New York Times articles written during the Kasparov-Deep Blue matchup which chart the rise of the machines.

Responding to defeat with the pride and tenacity of a champion, the I.B.M. computer Deep Blue drew even yesterday in its match against Garry Kasparov, the world’s best human chess player, winning the second of their six games and stunning many chess experts with its strategy.

Joel Benjamin, the grandmaster who works with the Deep Blue team, declared breathlessly: “This was not a computer-style game. This was real chess!”

He was seconded by others.

“Nice style!” said Susan Polgar, the women’s world champion. “Really impressive. The computer played a champion’s style, like Karpov,” she continued, referring to Anatoly Karpov, a former world champion who is widely regarded as second in strength only to Mr. Kasparov. “Deep Blue made many moves that were based on understanding chess, on feeling the position. We all thought computers couldn’t do that.”•

Garry Kasparov, the world chess champion, opened the third game of his six-game match against the I.B.M. computer Deep Blue yesterday in peculiar fashion, by moving his queen’s pawn forward a single square. Huh?

“I think we have a new opening move,” said Yasser Seirawan, a grandmaster providing live commentary on the match. “What should we call it?”

Mike Valvo, an international master who is a commentator, said, “The computer has caused Garry to act in strange ways.”

Indeed it has. Mr. Kasparov, who swiftly became more conventional and subtle in his play, went on to a draw with Deep Blue, leaving the score of Man vs. Machine at 1 1/2 apiece. (A draw is worth half a point to each player.) But it is clear that after his loss in Game 2 on Sunday, in which he resigned after 45 moves, Mr. Kasparov does not yet have a handle on Deep Blue’s predilections, and that he is still struggling to elicit them.•

In brisk and brutal fashion, the I.B.M. computer Deep Blue unseated humanity, at least temporarily, as the finest chess playing entity on the planet yesterday, when Garry Kasparov, the world chess champion, resigned the sixth and final game of the match after just 19 moves, saying, “I lost my fighting spirit.”

The unexpectedly swift denouement to the bitterly fought contest came as a surprise, because until yesterday Mr. Kasparov had been able to summon the wherewithal to match Deep Blue gambit for gambit.

The manner of the conclusion overshadowed the debate over the meaning of the computer’s success. Grandmasters and computer experts alike went from praising the match as a great experiment, invaluable to both science and chess (if a temporary blow to the collective ego of the human race) to smacking their foreheads in amazement at the champion’s abrupt crumpling.

“It had the impact of a Greek tragedy,” said Monty Newborn, chairman of the chess committee for the Association for Computing, which was responsible for officiating the match.

It was the second victory of the match for the computer — there were three draws — making the final score 3 1/2 to 2 1/2, the first time any chess champion has been beaten by a machine in a traditional match. Mr. Kasparov, 34, retains his title, which he has held since 1985, but the loss was nonetheless unprecedented in his career; he has never before lost a multigame match against an individual opponent.

Afterward, he was both bitter at what he perceived to be unfair advantages enjoyed by the computer and, in his word, ashamed of his poor performance yesterday.

“I was not in the mood of playing at all,” he said, adding that after Game 5 on Saturday, he had become so dispirited that he felt the match was already over. Asked why, he said: “I’m a human being. When I see something that is well beyond my understanding, I’m afraid.”•