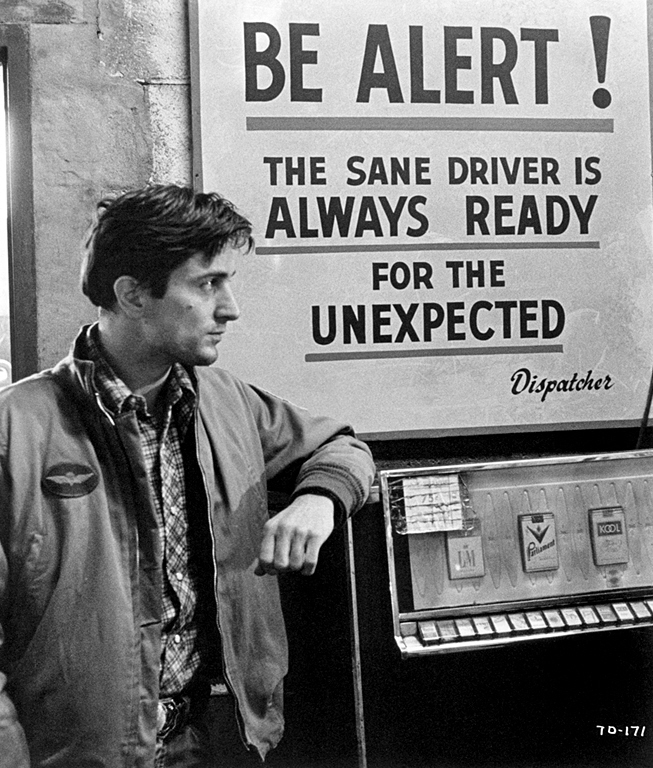

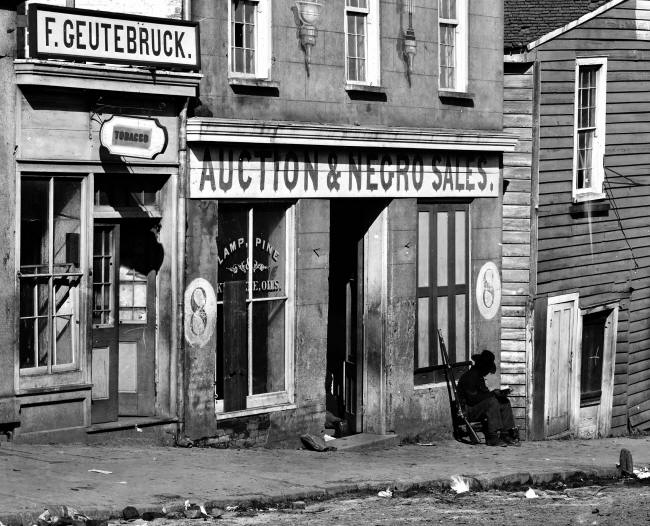

I took a NYC bus recently, an odd circumstance for a dedicated subway rider like myself, and it was a depressing experience in a way I didn’t anticipate. The stop at which I boarded was the culmination of an undercover sting operation, and those who hadn’t paid full fare along the line (just put small change in the box) or hopped on via the back door were loudly pointed out by plainclothes cops and herded off like murderers. There they were lined up and written tickets. A cursory glance at these “hardened criminals” showed them to be just sort of down-on-their luck working class people, who weren’t much different than anyone else on the bus, save a Metrocard or enough coins. I didn’t mind if my fare was subsidizing them, and it was tough seeing these struggling folks treated like perps just because they didn’t have enough money. It felt like they were mostly guilty of daring to be poor in New York City, of being on the losing end of a class war.

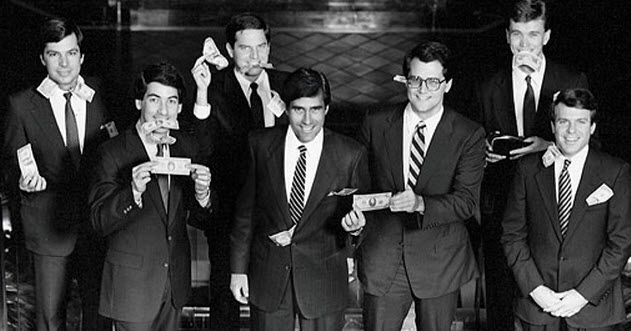

When Wall Street banks crashed the economy in 2008, those involved in the schemes weren’t pointed out and lined up. No tickets written. Perhaps that’s because they have enough money to avoid taking buses. Fact is, when you can hire lobbyists and buy politicians, you don’t have to really break the law to get what you want. You can have rules bent to your advantage so things that should be illegal are perfectly okay. That’s also class warfare, especially since such behavior had a direct impact on the fate of bus riders.

In a New York Times piece, Alan Feuer, who never disappoints, writes of a few super-rich people at least paying lip service to the problem of wealth inequality. His opening:

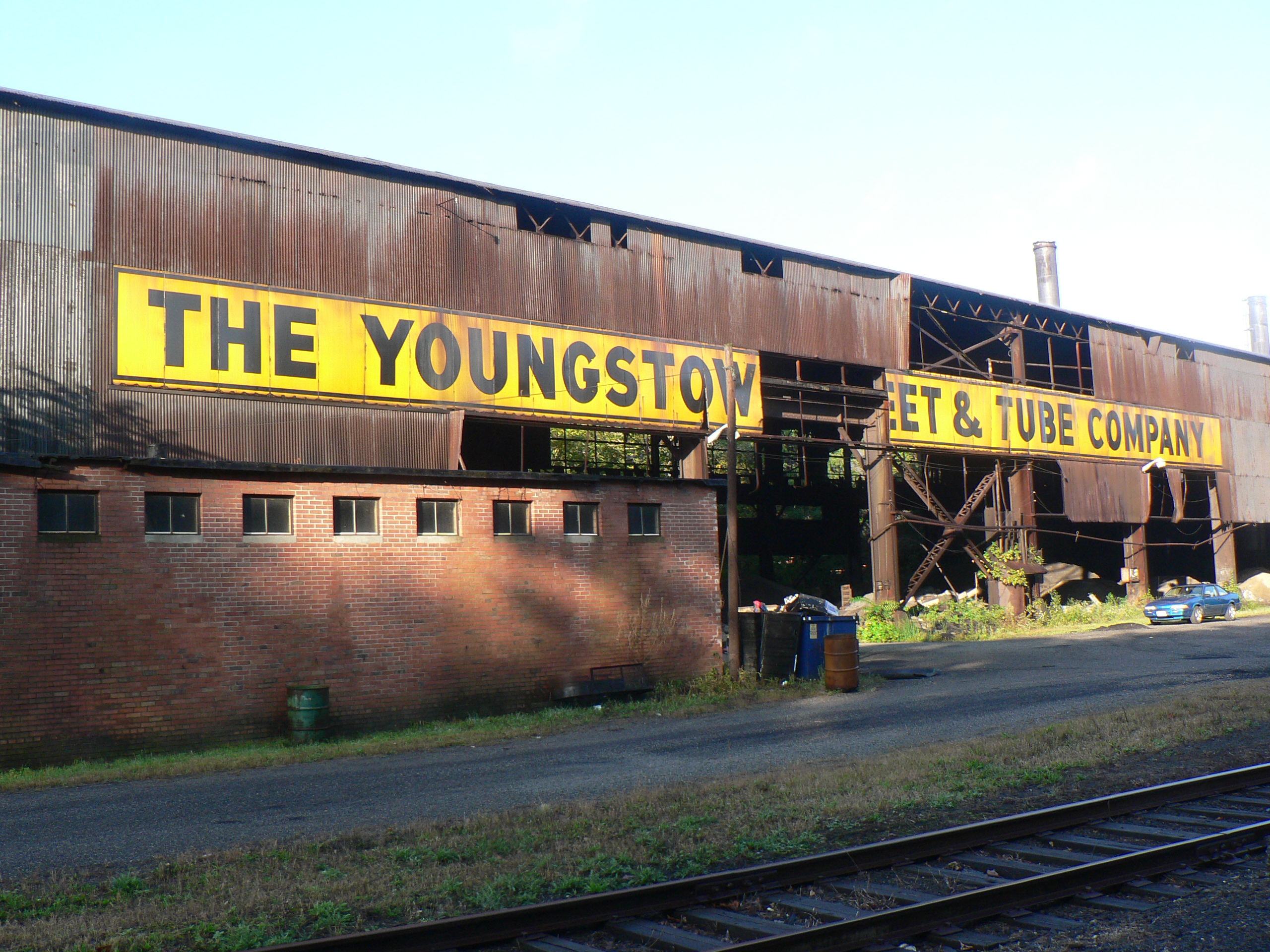

EARLIER this month, when the billionaire merchandising mogul Johann Rupert gave a speech at The Financial Times’ “luxury summit” in Monaco, he sounded more like a Marxist theoretician than someone who made his fortune selling Cartier diamonds and Montblanc pens. Appearing before a crowd of executives from Fendi and Ferrari, Mr. Rupert argued that it wasn’t right — or even good business — for “the 0.1 percent of the 0.1 percent” to raid the world’s spoils. “It’s unfair and it is not sustainable,” he said.

For several years now, populist politicians and liberal intellectuals have been inveighing against income inequality, an issue that is gaining traction among the broader body politic, as shown by a recent New York Times/CBS News poll that found that nearly 60 percent of American voters want their government to do more to reduce the gap between the rich and the poor. But in the last several months, this topic has been taken up by a different and unlikely group of advocates: a small but vocal band of billionaires.

In March, for instance, Paul Tudor Jones II, the private equity investor, gave a TED talk in which he proclaimed that the divide between the top 1 percent in the United States and the remainder of the country “cannot and will not persist.” Mr. Jones, who is thought to be worth nearly $5 billion, added that such divides have historically been resolved in one of three ways: taxes, wars or revolution.•