If gambling on Elon Musk’s plan to quickly establish a colony on Mars, it would be wise to bet the under considering it would be the greatest and most challenging undertaking in human history. But the likelihood that it’s at all possible for one well-funded visionary to have a shot at accomplishing such a feat says as a lot not only about science but society as well. Some thoughts:

- Wealth inequality has made us a weird and lopsided world. Sentences on automation like one recently in the WSJ, “[Target Corp.] could take a risk on a new breed of robots from a reclusive billionaire,” no longer seem stunning. The Digital Age has made a few us so overwhelmingly wealthy that individuals can compete with the biggest governments on the grandest projects in for-profit sectors and philanthropy. But there’s a very dark side to such a widening gap, whether its Peter Thiel deciding to a publication into bankruptcy or Palmer Luckey using his Facebook windfall to fund alt-right trolls to game online surveys and plant dubious memes in an effort to enable a Fascist like Donald Trump into the White House. Persons as rich as nations has the potential for great good and bad.

- Musk’s math in measuring the money needed to fund his first foray to Mars and provide the basic building blocks of a space society may wind up seeming as fanciful as a Paul Ryan budget, but regardless the price tag of such enterprises has fallen tantalizingly low thanks to the diminishing costs of the necessary tools, a culmination of decades of work bearing fruit in our times.

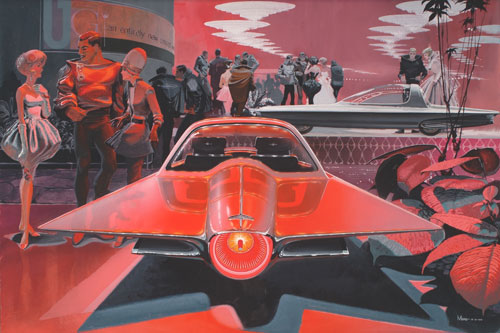

- Putting humans in space doesn’t make much sense to me within Musk’s time frame. Becoming a multi-planetary species as a hedge against disaster, environmental or otherwise, is understandable, but racing Homo sapiens to Mars doesn’t seem the best plan. A century of robots being dispatched to plumb the planets and experiment with building enclosed habitats and growing food in space. seems the wiser course. But I’m not a Silicon Valley billionaire, so I don’t get a vote.

In the Ars Technica piece “Musk’s Mars Moments,” Eric Berger assesses the feasibility of the audacious plan and the person responsible for it. The writer unsurprisingly believes the Space X founder is underestimating costs but doesn’t dismiss the proposal as impossible, especially if it should develop into a private-public hybrid. The opening:

Elon Musk finally did it. Fourteen years after founding SpaceX, and nine months after promising to reveal details about his plans to colonize Mars, the tech mogul made good on that promise Tuesday afternoon in Guadalajara, Mexico. Over the course of a 90-minute speech Musk, always a dreamer, shared his biggest and most ambitious dream with the world—how to colonize Mars and make humanity a multiplanetary species.

And what mighty ambitions they are. The Interplanetary Transport System he unveiled could carry 100 people at a time to Mars. Contrast that to the Apollo program, which carried just two astronauts at a time to the surface of the nearby Moon, and only for brief sojourns. Moreover, Musk’s rocket that would lift all of those people and propellant into orbit would be nearly four times as powerful as the mighty Saturn V booster. Musk envisions a self-sustaining Mars colony with at least a million residents by the end of the century.

Beyond this, what really stood out about Musk’s speech on Tuesday was the naked baring of his soul. Considering his mannerisms, passion, and the utter seriousness of his convictions, it felt at times like the man’s entire life had led him to that particular stage. It took courage to make the speech, to propose the greatest space adventure of all time. His ideas, his architecture for getting it done—they’re all out there now for anyone to criticize, second guess, and doubt.

It is not everyday that one of the world’s notables, a true difference-maker, so completely eschews caution and reveals his deepest ambitions like Musk did with the Interplanetary Transport System. So let us look at those ambitions—the man laid bare, the space hardware he dreams of building—and then consider the feasibility of all this. Because what really matters is whether any of this fantastical stuff can actually happen.•