Currently, Artificial Intelligence is either depressingly limited or on the cusp of taking all our jobs and becoming superintelligent. It depends on who you ask.

No one really knows the answers to these questions, not completely. Garry Kasparov doesn’t fret much about AI because he believes that outside of “closed systems,” like chess, humans are far better at navigating the world. Perhaps. But what of another board game like Go, which is technically a closed system but far more complex, almost infinitely so? Humans have been crushed far ahead of schedule in this pastime, so much so that its strategies are incomprehensible to even the world’s best carbon-based players. Is society, ultimately, more like chess or Go? I would say the latter.

The truth about AI lies somewhere in between—or at one of the poles. Time will tell.

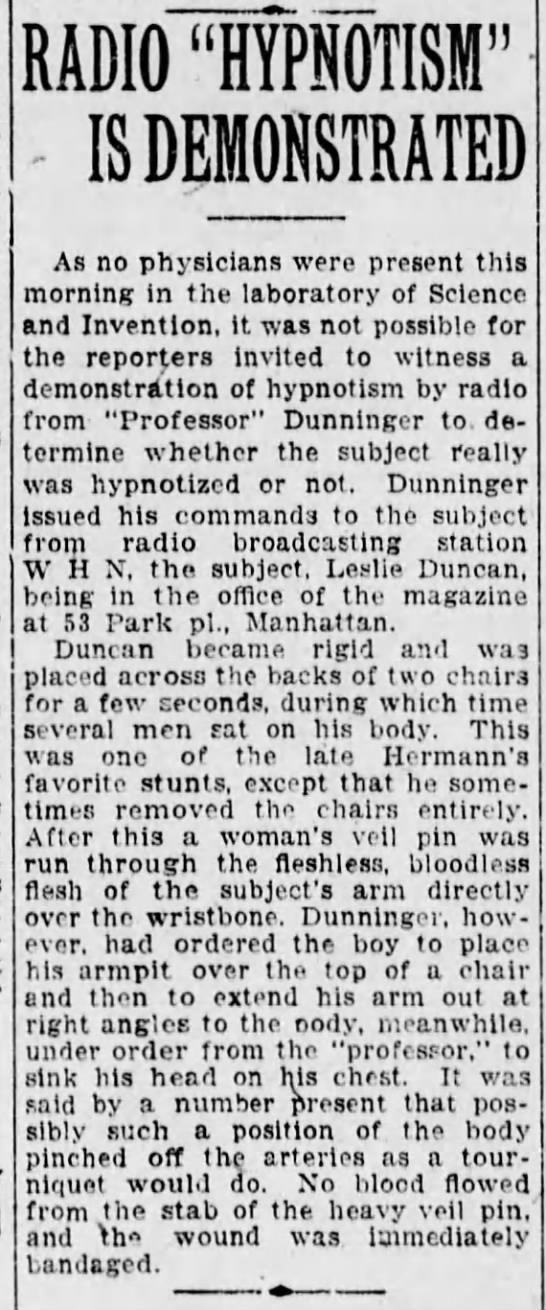

Two excerpts follow.

_____________________________

In “The AI That Has Nothing To Learn From Humans,” Dawn Chen’s excellent Atlantic piece, the author examines the almost otherwordly performance of Alpha Go Zero, which plays the game with an inscrutability so pronounced that trying to divine its motivations is akin to attempting to understanding the thinking of an octopus. An excerpt:

Since May, experts have been painstakingly analyzing the 55 machine-versus-machine games. And their descriptions of AlphaGo’s moves often seem to keep circling back to the same several words: Amazing. Strange. Alien.

“They’re how I imagine games from far in the future,” Shi Yue, a top Go player from China, has told the press. A Go enthusiast named Jonathan Hop who’s been reviewing the games on YouTube calls the AlphaGo-versus-AlphaGo face-offs “Go from an alternate dimension.” From all accounts, one gets the sense that an alien civilization has dropped a cryptic guidebook in our midst: a manual that’s brilliant—or at least, the parts of it we can understand.

Will Lockhart, a physics grad student and avid Go player who codirected The Surrounding Game (a documentary about the pastime’s history and devotees) tried to describe the difference between watching AlphaGo’s games against top human players, on the one hand, and its self-paired games, on the other. (I interviewed Will’s Go-playing brother Ben about Asia’s intensive Go schools in 2016.) According to Will, AlphaGo’s moves against Ke Jie made it seem to be “inevitably marching toward victory,” while Ke seemed to be “punching a brick wall.” Any time the Chinese player had perhaps found a way forward, said Lockhart, “10 moves later AlphaGo had resolved it in such a simple way, and it was like, ‘Poof, well that didn’t lead anywhere!’”

By contrast, AlphaGo’s self-paired games might have seemed more frenetic. More complex. Lockhart compares them to “people sword-fighting on a tightrope.”

Expert players are also noticing AlphaGo’s idiosyncrasies. Lockhart and others mention that it almost fights various battles simultaneously, adopting an approach that might seem a bit madcap to human players, who’d probably spend more energy focusing on smaller areas of the board at a time. According to Michael Redmond, the highest-ranked Go player from the Western world (he relocated to Japan at the age of 14 to study Go), humans have accumulated knowledge that might tend to be more useful on the sides and corners of the board. AlphaGo “has less of that bias,” he noted, “so it can make impressive moves in the center that are harder for us to grasp.”

Also, it’s been making unorthodox opening moves. Some of those gambits, just two years ago, might have seemed ill-conceived to experts. But now pro players are copying certain of these unfamiliar tactics in tournaments, even if no one fully understands how certain of these tactics lead to victory. For example, people have noticed that some versions of AlphaGo seem to like playing what’s called a three-three invasion on a star point, and they’re experimenting with that move in tournaments now too. No one’s seeing these experiments lead to clearly consistent victories yet, maybe because human players don’t understand how best to follow through.

Some moves AlphaGo likes to make against its clone are downright incomprehensible, even to the world’s best players.•

_____________________________

In “The Human Strategy,” Sandy Pentland’s piece at Edge, the Artificial Intelligence pioneer writes that “current AI machine-learning things are just dead simple stupid.” Perhaps, but that will change, and as a means of creating a less dystopic path forward, Pentland believes humans can be informed about our own systems by studying our silicon counterparts. He also thinks we can tame AI to a good degree by keeping a “human in the loop,” which is either hopeful about the future of our species or ignorant about our past. Even if we can chasten machines, society will only be as good as the humans who inhabit it. That’s as much a risk as a guarantee, especially since the tools at our disposal will be far more powerful.

An excerpt:

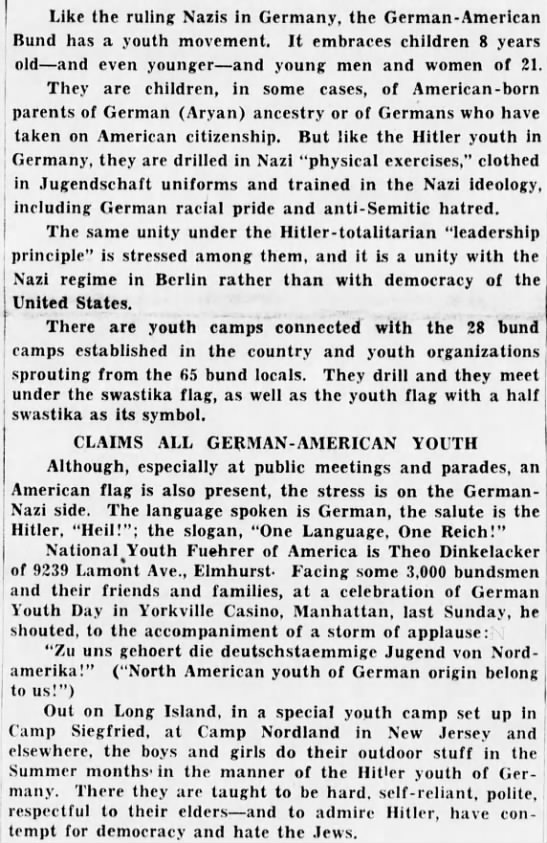

On Polarization and Inequality

Today, we have incredible polarization and segregation by income almost everywhere in the world, and that threatens to tear governments and civil society apart. We have increasing population, which is part of the root of all those things. Increasingly, the media are failing us, and the downfall of media is causing people to lose their bearings. They don’t know what to believe. It makes it easy for people to be manipulated. There is a real need to put a grounding under all of our cultures of things that we all agree on, and to be able to know which things are working and which things aren’t.

We’ve now converted to a digital society, and have lost touch with the notions of truth and justice. Justice used to be mostly informal and normative. We’ve now made it very formal. At the same time, we’ve put it out of the reach of most people. Our legal systems are failing us in a way that they didn’t before precisely because they’re now more formal, more digital, less embedded in society.

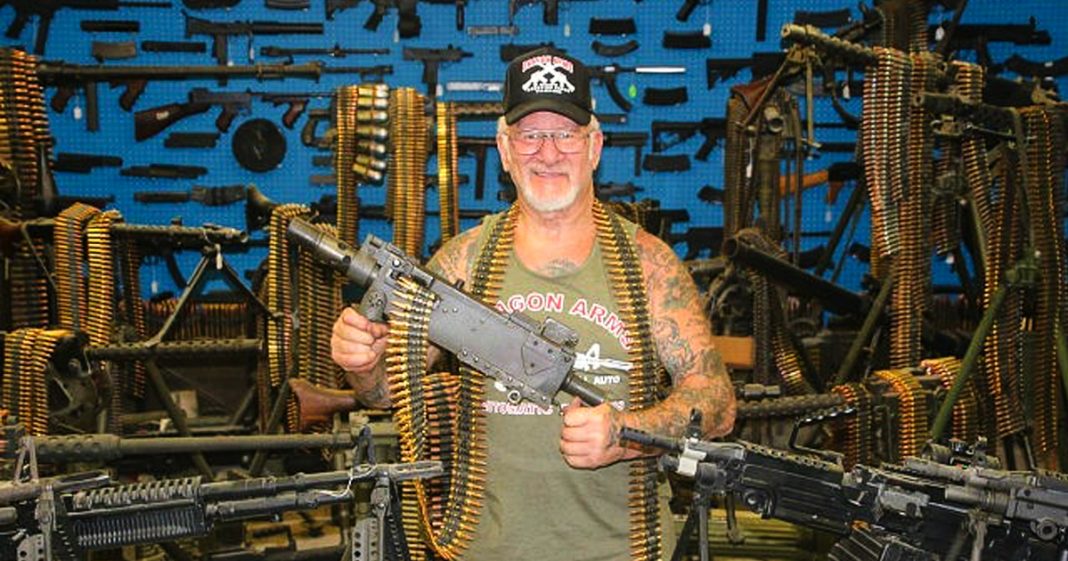

Ideas about justice are very different around the world. People have very different values. One of the core differentiators is, do you remember when the bad guys came with guns and killed everybody? If you do, your attitude about justice is different than the average Edge reader. Were you born into the upper classes? Or were you somebody who saw the sewers from the inside?

A common test I have for people that I run into is this: Do you know anybody who owns a pickup truck? It’s the number-one selling vehicle in America, and if you don’t know people like that, that tells me you are out of touch with more than fifty percent of America. Segregation is what we’re talking about here, physical segregation that drives conceptual segregation. Most of America thinks of justice, and access, and fairness as being very different than the typical, say, Manhattanite.

If you look at patterns of mobility—where people go—in a typical city, you find that the people in the top quintile—white-collar working families—and the bottom quintile—people who are sometimes on unemployment or welfare—never see each other. They don’t go to the same places; they don’t talk about the same things; they see the world very differently. It’s amazing. They all live in the same city, nominally, but it’s as if it were two completely different worlds. That really bothers me.

On Extreme Wealth

Today’s ultra-wealthy, at this point, fifty percent of them have promised to give away more than fifty percent of their wealth, creating a plurality of different voices in the foundation space. Gates is probably the most familiar example. He’s decided that if the government won’t do it, he’ll do it. You want mosquito nets? He’ll do it. You want antivirals? He’ll do it. We’re getting different stakeholders taking action, in the form of foundations that are dedicated to public good. But they have different versions of public good, which is good. A lot of the things that are wonderful about the world today come from actors outside government like the Ford Foundation or the Sloan Foundation, where the things they bet on are things that nobody else would bet on, and they happened to pan out.

Sure, these billionaire are human and they have the human foibles. And yes, it’s not necessarily the way it should be. On the other hand, the same thing happened when we had railways. People made incredible fortunes. A lot of people went bust. We, the average people, got railways out of it. Pretty good. Same thing with electric power. Same thing with many of these things. There’s a churning process that throws somebody up and later casts them or their heirs down.

Bubbles of extreme wealth happened in the 1890s, too, when people invented steam, and railways, and electricity. These new industries created incredible fortunes, which were all gone within two or three generations.

If we were like Europe, I would worry. What you find in Europe is that the same family has wealth for hundreds of years, so they’re entrenched not just in terms of wealth, but in terms of the political system and other ways. But so far, the U.S. has avoided this: extreme wealth hasn’t stuck, which is good. It shouldn’t stick. If you win the lottery, you make your billion dollars, but your grandkids have to work for a living.

On AI and Society

People are scared about AI. Perhaps they should be. But you need to realize that AI feeds on data. Without data, AI is nothing. You don’t actually have to watch the AI; you have to watch what it eats and what it does. The framework that we’ve set up, with the help of the EU and other people, is one where you can have your algorithms, you can have your AI, but I get to see what went in and what went out so that I can ask, is this a discriminatory decision? Is this the sort of thing that we want as humans? Or is this something that’s a little weird?

The most revealing analogy is that regulators, bureaucracies, parts of the government, are very much like AIs: They take in these rules that we call law, and they elaborate them, and they make decisions that affect our lives. The part that’s really bad about the current system is that we have very little oversight of these departments, regulators, and bureaucracies. The only control we have is the ability to elect somebody different. Let’s make that control over bureaucracies a lot more fine-grained. Let’s be able to look at every single decision, analyze them, and have all the different stakeholders come together, not just the big guys. Rather like legislatures were supposed to be at the beginning of the U.S.

In that case, we can ask fairly easily, is this a fair algorithm? Is this AI doing things that we as humans believe is ethical? It’s called human in the loop.•