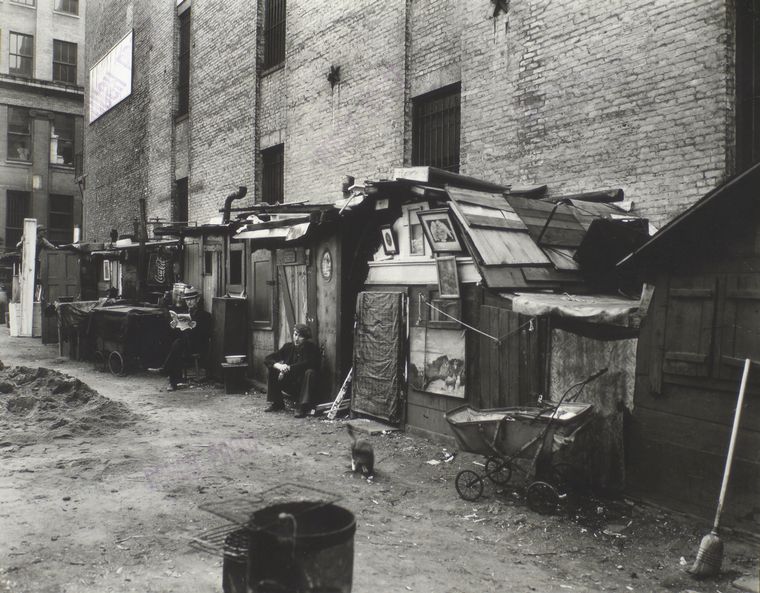

A 1981 interview with famed street photographer Garry Winogrand.

Winogrand’s shooting style, as recalled by a former student: “We quickly learned Winogrand’s technique–he walked slowly or stood in the middle of pedestrian traffic as people went by. He shot prolifically. I watched him walk a short block and shoot an entire roll without breaking stride. As he reloaded, I asked him if he felt bad about missing pictures when he reloaded. ‘No,’ he replied, ‘there are no pictures when I reload.’ He was constantly looking around, and often would see a situation on the other side of a busy intersection. Ignoring traffic, he would run across the street to get the picture.

Incredibly, people didn’t react when he photographed them. It surprised me because Winogrand made no effort to hide the fact that he was standing in way, taking their pictures. Very few really noticed; no one seemed annoyed. Winogrand was caught up with the energy of his subjects, and was constantly smiling or nodding at people as he shot. It was as if his camera was secondary and his main purpose was to communicate and make quick but personal contact with people as they walked by.”