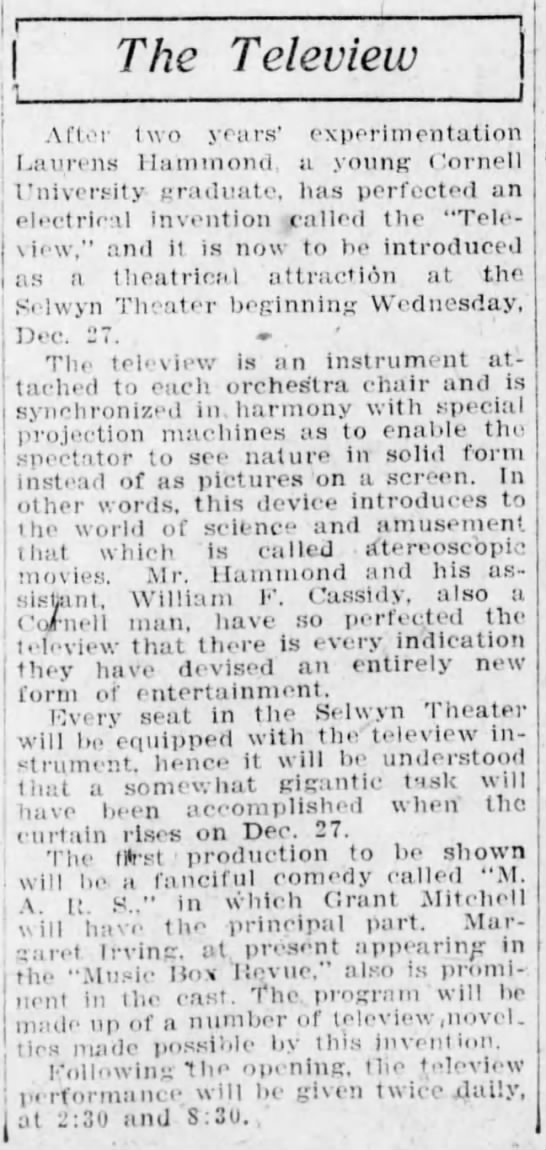

It is three weeks before the outdoor rock concert, for which we’ve rented a vast football stadium in Phoenix. The scene will run at most five to eight minutes on screen. The action involves Kris showing off to Barbra by taking her onstage at a huge concert. Drunk and coked up, he abandons the music and, trying to ride a motorcycle onstage, loses control and zooms off into the audience. It is the last straw and will ruin his career. We must fill the stadium, which takes some 40,000 or 50,000 people. It is essential to get some feeling on screen of the weight and size and pressure in the lives of rock musicians. Jon has been full of mad schemes. Now, only three weeks away from shooting, the planned all-day live concert turns out to be nonexistent. This is a disaster of such magnitude that I cannot think about it. All I can do is shoot whatever is there the day we arrive.

The action I have planned is detailed in sketches. Barbra and Jon want to see them. “This is the heart of the picture, this is the action part for people like me!” Jon says, bouncing around the office. He acts out his idea of how to do it. He wants to hire Evel Knievel for $25,000, construct a jumping ramp so Knievel, doubling for Kris, will drive the bike off the stage through the paying customers for a hundred yards, scattering them like bowling pins, and, hitting the ramp, fly into the air from the audience 150 feet back over the stage and crash into the instruments. The stunt of the century. Something nobody who sees this picture will ever forget. “For people like me, who like action. We got to set some action, some excitement into this picture.” He is pacing about feverishly. I look at Barbra. She’s not listening. “Listen, where are the close-ups?” she asks. “There are never any close-ups in this picture. When I worked with Willy Wyler, we had close-ups in every scene.”

I call her attention to some of the more recent close-ups, forgetting my decision not to discuss these things with her. Soon we are embroiled in exactly how close up a close-up really has to be to be called a close-up. Jon studies the storyboard for the stunt. “This is shit,” he says.

We have no concert, I remind him. Let’s get the concert organized before we worry over the stunt. Promoter Bill Graham is hired to get together a concert. After a month of Jon’s waffling about, Graham has it all nailed down in a few days, together with a schedule that allots me four hours on stage with camera, in two two-hour sessions. Peter Frampton is the topliner. We are selling tickets at $3.50 apiece. We might even make money. “I’m paying him a fortune.” Jon crows, “but he’s worth it. He’s tough, he’s like me, he’s a street fighter.”

Evel Knievel has been forgotten.

We look at a first assembly of major scenes, the recreation of the Leon Russell piano incident. Kris croaks the lyrics to her music with a boyish delight. He sounds as if the music and the words had only that moment occurred to him. He is perfect. She is magical. Words are no good for it; the scene simply makes you feel wonderful. Barbra is crying. “It’s better than my dreams!” she says. And then she turns to Peter Zinner, the editor. “But Peter! You used the wrong take! Why did you do that? That was a mistake!” We patiently explain the difficulties of cutting, how sometimes you have to sacrifice a marginally better take in order to get a better rhythm, or to be able to use some other piece that is essentially better. She is unconvinced.

“When I get the film,” she says to me later, “will he do it my way?”

I check. Barbra’s companies own the negative. She has final cut on the film. Barbra is preoccupied with a press party Warners is giving, flying in reporters and photographers from all over the country for a conference, a luncheon press party on the set and the outdoor rock concert the next day.

Kris, uptight about press, worried over his music, is tense, angry over her interference. His new record has just come out and been panned by Rolling Stone and most everyone else. He’s drinking tequila washed down with cold beer.

Barbra rehearses with the band on her numbers and uses up Kris’s time, so he has no rehearsal. Coldly furious, he refuses to come out of his trailer. “Goddamnit!” he says. “I’ve got to go out and play it in front of 60.000 people, but she doesn’t give a damn.”

Barbra and I are trying to explain a minor change; we agree for once, but Kris has had all he can handle. He doesn’t want to be told what to do with his music. He explodes. Barbra explodes. The mikes are open: they are screaming at each other over a sound system that draws complaints from five miles away. The press is delighted. This is what they came for. Sulks in trailers. Jon Peters threatening Kris. Kris talking tougher. The director knocking on trailer doors, playing Kissinger. Notable quotes. Quotable notables. You read about it in Time.

Now our differences have become news events. It heightens the tension, and the feeling of being perpetually misunderstood. These clashes happen on all pictures: they become part of the creative process from which the picture emerges. They are unavoidable. And the press is uncontrollable and mischievous. They know a good story when they see one, but we wish they’d check their facts.

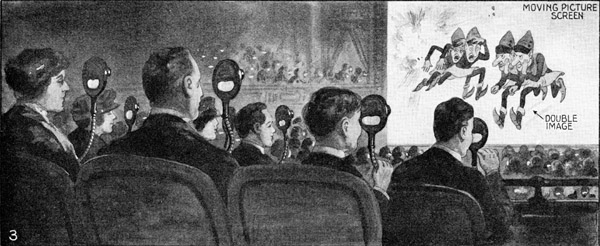

At seven o’clock in the morning, the dawn brushes the crowd with blood orange. They are there. By mid-morning some 55,000 curiously clean and docile people are listening to the opening acts. It is overwhelming. The sheer size and sound of the crowd reduce our conflicts and tensions to a proper perspective. But the communications are incredibly difficult. I have a schedule of shots in mind: I run from setup to setup. At the morning break, the two-hour session during which we have the stage, I face horror: The props and set dressing for our action have all been pushed back and replaced with instruments and amps and paraphernalia of the various acts onstage. The first hour of our allotted two is wasted moving furniture to match what I’ve already shot.

The crowd is mercurial. Fifty-five thousand strong, they scream and chant: “No more filming, no more filming!” though we haven’t even begun. We make the shot. Things break, a plug-in wire for Kris’s guitar is too short, nothing works. Nobody can hear. The noise, the pandemonium, the incipient panic are all but overwhelming. I remember the advice of a London bobby about facing crowds and one’s own tendency to panic: Imagine a piano wire attached to the inside of one’s skull, stretched tight all the way through the body and down to the center of the earth. Nothing can move you. Zen.•