It bothers me to no end that Ron Howard’s Cinderella Man depicts boxer Max Baer as a semi-psychotic villain for the sake of narrative convenience. It’s cinematic license taken to an ugly extreme.

In general, the Hollywood biopic is a troubling compromise that will satisfy no one completely–or at least it shouldn’t. The best-case scenario is that you come away with some sort of an impressionistic truth but realize that, no, Richard Nixon never made a drunken, late-night phone call to David Frost.

Perhaps each film should be labeled with a Surgeon General-ish warning: “Believing the events of this film are true can be injurious to history.” That agreement has always been tacit, but I can’t tell you how many people over the years have cited the “facts” in Oliver Stone’s overwrought bullshit JFK. There’s really no easy answer.

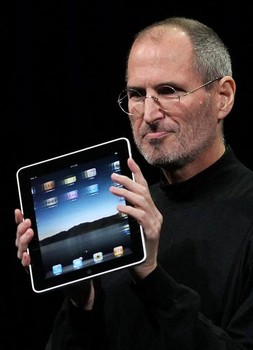

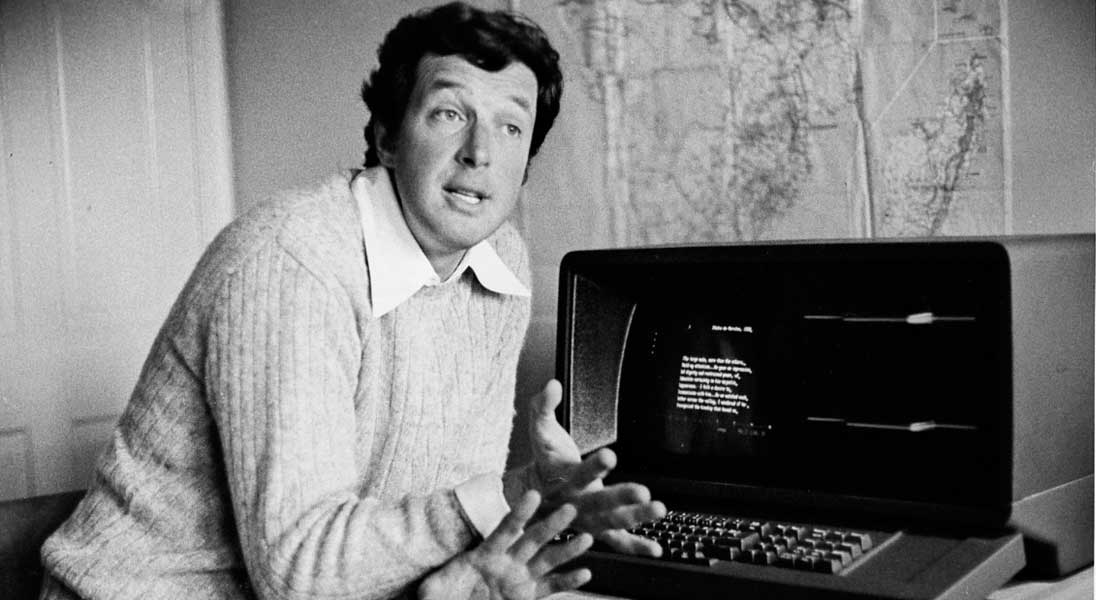

Steven Levy, who reported on Steve Jobs and knew him, was troubled by his portrayal in the new Aaron Sorkin-Danny Boyle film. In a Backchannel Q&A, he interviewed the former about writing a screenplay on an actual historical figure. An excerpt:

Steven Levy:

Let’s take a specific example of history and fabrication. In the first act, you have Steve’s obsession with the 1983 Time Magazine story about him. You’re right to zero in on that — he was complaining about that when I interviewed him for Rolling Stone before the Macintosh launch, and he was complaining about it 20 years later.

Aaron Sorkin:

That’s right.

Steven Levy:

But you took it a step farther. In your screenplay, someone at Apple ordered boxes of the magazine and was going to place one on every seat in the shareholder’s meeting until someone figured out it would make Steve crazy. In real life, that didn’t happen.

Aaron Sorkin:

Right. That’s exactly the kind of thing I don’t mind making up. Here is what’s true, here is the important truth. As a matter of happy coincidence, Walter Isaacson, who was at Time Magazine in 1983 when all this happened, was able to tell me that Steve was never in the conversation for Man of the Year. Steve had always blamed Dan Kottke for spilling the beans in that article about Steve having to take a paternity test and that whole situation with Lisa and believed that was the reason why he didn’t get the cover. But, as Walter pointed out, it had nothing to do with Kottke — if you look at the cover, it’s a sculpture of a man at a desk with a computer, and that sculpture would have had to have been commissioned months and months in advance. In fact, the sculptor himself is a well known guy whose name I forget.

So that information is something that I want to use. I want to use it to introduce the paternity issue, I want to use it because it’s going to pay off in the third act both when Joanna [Hoffman] is giving a demonstration of his reality distortion field… And the final payoff is that Lisa, who now has Internet access at school, has read it — has read about her father denying that he’s not her father.

So I never worried that what the audience was going to go away with was there were cartons and cartons of Time Magazine backstage at this event. It didn’t seem to be important that the audience gets that right or wrong, that it was a fact of history. It has no negative effect on anyone’s life. You can’t say, who was the idiot who put those cartons of Time Magazine backstage? But that [represented] something truer and I felt this was an interesting way to dramatize it.•