"I worked with Freud in Vienna. We broke over the concept of penis envy. Freud felt that it should be limited to women."

The twentieth century may have been known as the “Century of the Self,” but it was a time when psychotherapy was ascendant, people were questioning their egos and phrases like “Me Decade” were used in the pejorative. There was a sense of introspection and healing, as wrong-minded as the methods may have been at times, as opposed to the sheer exhibitionism that succeeded it. This century may end up being the “Century of You,” but it still seems to be just another way to say “Me.” And minus the introspection.

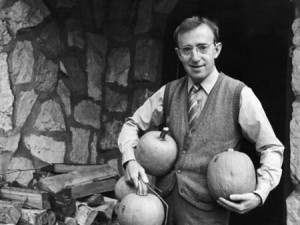

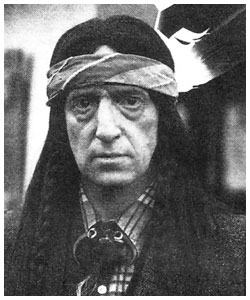

Woody Allen’s pitch-perfect period-piece mockumentary profiles a unique and now-forgotten Jazz Age character, the protean protagonist Leonard Zelig. A man who fears that being himself will lead to unpopularity, Zelig adapts the personas, professions and attitudes of whomever he encounters. In tall tale tradition, he is able to actually alter his physical appearance. When surrounded by heavyset men, his belly distends. In Paris jazz clubs, his skin darkens so that he can play with musicians of color. In Chicago bars, scars suddenly crawl across his face when he rubs elbows with gangsters. The unusual talent allows Zelig to insert himself into a variety of famous historical moments–and eventually lands him in a mental institution, where he comes under the care of Dr. Eudora Fletcher (Mia Farrow). She hopes to cure the chameleon and make her career all at once. Of course, she encounters difficulties since Zelig insists that he’s also a psychiatrist, wanting to resemble her.

Woody Allen’s pitch-perfect period-piece mockumentary profiles a unique and now-forgotten Jazz Age character, the protean protagonist Leonard Zelig. A man who fears that being himself will lead to unpopularity, Zelig adapts the personas, professions and attitudes of whomever he encounters. In tall tale tradition, he is able to actually alter his physical appearance. When surrounded by heavyset men, his belly distends. In Paris jazz clubs, his skin darkens so that he can play with musicians of color. In Chicago bars, scars suddenly crawl across his face when he rubs elbows with gangsters. The unusual talent allows Zelig to insert himself into a variety of famous historical moments–and eventually lands him in a mental institution, where he comes under the care of Dr. Eudora Fletcher (Mia Farrow). She hopes to cure the chameleon and make her career all at once. Of course, she encounters difficulties since Zelig insists that he’s also a psychiatrist, wanting to resemble her.

In a twist, Zelig’s ability to subsume his own ego is what helps sustain him at a vital moment. Despte this stroke of good luck, Zelig continues to find it difficult to walk the fine line between utter conformity and unbridled ego. But at least he was trying.•

Recent Film Posts:

- Classic DVD: Fahrenheit 451 (1966)

- New DVD: Waste Land.

- Classic DVD: Woman in the Dunes (1964)

- Classic DVD: RoboCop (1987)

- Classic DVD: King of Comedy (1982)

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Little Murders (1971)

- Classic DVD: The Passenger (1975)

- New DVD: Dogtooth

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Rivers and Tides (2003)

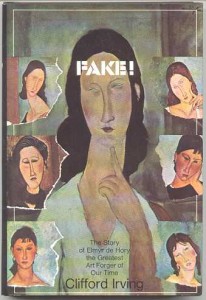

- Classic DVD: F for Fake (1974)

- New DVD: The Art of the Steal

- Classic DVD: The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

- Classic DVD: Fast, Cheap & Out of Control (1997)

- Classic DVD: Umberto D. (1952)

- Classic DVD: The Wicker Man (1973)

- Classic DVD: Blow-Up (1966)

- Classic DVD: Invasion of the Bodysnatchers (1978)

- Classic DVD: The Stepford Wives (1975)

- Classic DVD: Rollerball (1975)

- New DVD: Exit Through the Gift Shop

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Stay Hungry (1976)

- Classic DVD: Westworld (1973)

- Classic DVD: Slacker (1991)

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Decasia: The State of Decay (2002)

- Classic DVD: 32 Short Films About Glenn Gould (1993)