From “The Devil and John Holmes,” Mike Sager’s 1989 Rolling Stone article about the further decline of porn star John Holmes, whose rapacious drug habit led him from adult films to even darker and more desperate corners of Tinseltown in the 1980s:

“Blood! Blood! So much blood!” Holmes was having a nightmare. Tossing and moaning, punching and kicking. “So much blood!” he groaned over and over.

Jeana was scared to death. She didn’t know what to do. Wake him? Let him scream? It was Thursday, July 2nd, 1981. After bathing at Sharon’s, Holmes had come here, to this motel in the Valley. He walked through the door, flopped on the bed, passed out.

Jeana sat very still on the edge of the bed, watching aTV that was mounted on the wall. After a while, the news. The top story was something about a mass murder. Four bodies. A bloody mess. A house on Wonderland Avenue. Jeana stood up, moved closer to the tube. “That house,” she thought. Things started to click. “I’ve waited outside that house. Isn’t that where John gets his drugs?”

Hours passed, John woke. Jeana said nothing. They made a run to McDonald’s for hamburgers. They watched some more TV. Then came the late-night news.The cops were calling it the Four on the Floor Murders. Dead were Joy Miller, Billy DeVerell, Ron Launius, Barbara Richardson. The Wonderland Gang. The murder weapon was a steel pipe with threading at the ends. Thread marks found on walls, skulls, skin. House tossed by assailants. Blood and brains splattered everywhere, even on the ceilings. The bodies were dis- covered by workmen next door; they’d heard faint cries from the back of the house: “Help me. Help me.” A fifth victim was carried out alive. Susan Launius, 25, Ron Launius’s wife. She was in intensive care with a severed finger and brain damage.The murders were so brutal that police were comparing the case to the Tate-LaBianca murders by the Manson Family.

Holmes and Jeana watched from the bed. Jeana was afraid to look at John. She cut her eyes slowly, caught his profile. He was frozen. The color drained from his face. She actually saw it. First his forehead, then his cheeks, then his neck. He went white.

Jeana said nothing. After a while, the weather report came on. She cleared her throat “John?”

“What?”

“You had this dream. You know, when you were sleeping? You said something about blood.”

Holmes’s eyes bulged. He looked very scared. She’d never seen him look scared before. “Yeah, well, uh,” he said. “Um, I lifted the trunk of the car, and I gave myself a nosebleed yesterday. Don’t worry.”

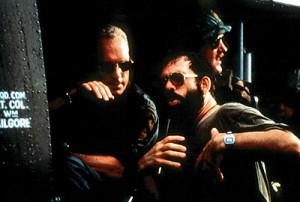

Paul Thomas Anderson providing commentary for scene from the Holmes documentary Exhausted.