Whenever there is a succession of 3-D films, you know Hollywood is in trouble. When the studio system was in its dotage during the 1950s, before the industry knew enough to rejuvenate itself by handing over the keys to the motorcycle to Easy Riders and other wild-eyed independents, it relied on 3-D to fill the coffers. Right now, the Dream Factory in California is located more in Silicon Valley than Hollywood. Science fiction no longer predicts science as the technology sector has the better ideas. And the movie industry responds with an over-reliance on gimmicks.

While the hunger for 3-D has abated somewhat in America, the world market has yet been satisfied, so even the mad genius auteur Werner Herzog has been given the opportunity to work with the effect in Cave of Forgotten Dreams. The film is an exploration of the Chauvet Cave in Southern France, which was discovered in 1994 by Eliette Brunel-Deschamps, Christian Hillaire, and Jean-Marie Chauvet. It bears the most historical artwork known to humankind on its walls, elaborate drawings of megafauna, human beings and creatures that combine the two, which were made at least 32,000 years ago. But Cave of Forgotten Dreams isn’t a mere art-history documentary, but rather a tacit struggle between Herzog and the 3-D illusion itself, which has a knack for directing directors, for wrestling the story from their hands.

It’s not completely a fair fight, either. Herzog not only has to deal with technical necessities of 3-D but is also hampered by the fragility of the cave, which demands that Herzog work from bended knee (sometimes in a metaphorical sense, sometimes not), not use too many cameras or lights, not get too close, not get his hands dirty. Whether he has been running headlong into the maw of a bubbling volcano (“La Soufriere”) or dragging a riverboat over a mountain into the jungle (Fitzcarraldo), Herzog is no stranger to obstructions forming his art. He is, however, alien to not being allowed to challenge the elements and having to genuflect in awe rather than form an adversarial relationship.

Making this movie for History Films (a subsidiary of the History Channel) has its restrictions, too. In addition to being a great artist, Herzog is a canny journalist, asking questions others wouldn’t pose, tugging at loose threads that most would never notice. His films are amazing as much for his powers of observation as for his daring. In one scene the director interviews an archaeologist who used to be a circus man. A scene that would have been a long and fascinating digression in a usual Herzog film is instead glossed over in favor of more standard storytelling, a concession that seemingly was made for the producers.

That’s the overall tone of the film: handsome and reverential with the requisite 3D-motion shots, but not Herzogian, lacking his insane brilliance. Until the five-minute “Postscript” section, that is. Herzog discovers a nuclear power plant less than 20 miles from the priceless cave. A second startling discovery is a nearby greenhouse that uses the warm water runoff from the power plant to grow hothouse flowers and allow albino crocodiles to thrive. The past, the present and the future unite against odd scenes of ferocious reptiles in an almost operatic way. The Herzog magic emerges in these moments, and we see the wry storytelling and resourcefulness that always restores Hollywood once its gimmicks run aground. In these scenes, Herzog’s been able to traverse one of the biggest obstacles of his career, one that is more ominous than a volcano or jungle–technology itself.•

You are currently browsing the archive for the Film category.

Tags: Christian Hillaire, Eliette Brunel-Deschamps, Jean-Marie Chauvet, Werner Herzog

Jean-Luc Godard on TV’s creeping influence on film. From Room 666, 1982.

See also:

- Dick Cavett interviews Godard. (1980)

Tags: Jean Luc-Godard

Katharine Hepburn talks about aging in America, 1979.

Tags: Katherine Hepburn

Laurie Winer writing in the Los Angeles Review of Books about Brian Kellow’s new Pauline Kael bio:

“Kael assumed national prominence in 1967, exactly when movies were taking quantum leaps in depictions of sex and violence, causing, as such leaps always do, anguish among cultural gatekeepers. Her review of Bonnie and Clyde marked Kael’s real debut in the New Yorker — she had previously published one article there about movies on TV. With his review of the same film, Bosley Crowther saw his 27-year reign as movie critic at the New York Times come to an end; Kael knew how to read the new graphic nihilism, and Crowther, her avowed nemesis, was left in the dark. Crowther had long been a powerful critic, and he had had his day, opposing Eugene McCarthy and censorship, and helping Americans to accept foreign films such as Open City and The Bicycle Thief. Now he was exposed as perilously out of touch. He was such an advocate of film as a force for betterment that he could hardly tell one violent movie from another. He called Bonnie and Clyde ‘a cheap piece of bald-faced slapstick comedy that treats the hideous depredation of that sleazy, moronic pair as though they were as full of fun and frolic as the jazz-age cut-up in Thoroughly Modern Millie.’ The resistance to this position was so strong that he wrote a second screed, precipitating his forced retirement as a film critic at the end of 1967.

Kael’s response to Arthur Penn’s film was so visceral because she sensed it marked a change in her own life as well as a change in movies. She was 48 years old, the single mother of a daughter, a person who had come from a West Coast farming family and who had struggled long and hard and with precious little recognition. With Bonnie and Clyde she finally came into her own as a critic of stature, someone who could influence the course of events, and she was eager to insert herself into the cultural moment: ‘The audience is alive to it,’ she wrote of the film, as if anyone with sense felt her excitement:

Our experience as we watch it has some connection with the way we reacted to movies in childhood: with how we came to love them and to feel they were ours — not an art that we learned over the years to appreciate but simply and immediately ours.”

••••••••••

PK + WA, 1975:

See also:

Tags: Brian Kellow, Laurie Winer, Pauline Kael

Terry Gilliam, trying to ensure he never works in Hollywood again, explains the difference between Spielberg and Kubrick. (Thanks Open Culture.)

I originally read Daniel Zalewski’s excellent New Yorker profile of filmmaker Guillermo del Toro in the print version and never realized until now that it’s online for free. Even if you’re not a fan of Del Toro’s work, you’ll probably enjoy it since the article is pretty much perfect. The opening:

In 1926, Forrest Ackerman, a nine-year-old misfit in Los Angeles, visited a newsstand and bought a copy of Amazing Stories—a new magazine about aliens, monsters, and other oddities. By the time he reached the final page, he had become America’s first fanboy. He started a group called the Boys’ Scientifiction Club; in 1939, he wore an outer-space outfit to a convention for fantasy aficionados, establishing a costuming ritual still followed by the hordes at Comic-Con. Ackerman founded a cult magazine, Famous Monsters of Filmland, and, more lucratively, became an agent for horror and science-fiction writers. He crammed an eighteen-room house in Los Feliz with genre memorabilia, including a vampire cape worn by Bela Lugosi and a model of the pteranodon that tried to abscond with Fay Wray in King Kong. Ackerman eventually sold off his collection to pay medical bills, and in 2008 he died. He had no children.

But he had an heir. In 1971, Guillermo del Toro, the film director, was a seven-year-old misfit in Guadalajara, Mexico. He liked to troll the city sewers and dissolve slugs with salt. One day, in the magazine aisle of a supermarket, he came upon a copy of Famous Monsters of Filmland. He bought it, and was so determined to decode Ackerman’s pun-strewed prose—the letters section was called Fang Mail—that he quickly became bilingual.

Del Toro was a playfully morbid child. One of his first toys, which he still owns, was a plush werewolf that he sewed together with the help of a great-aunt. In a tape recording made when he was five, he can be heard requesting a Christmas present of a mandrake root, for the purpose of black magic. His mother, Guadalupe, an amateur poet who read tarot cards, was charmed; his father, Federico, a businessman whom del Toro describes, fondly, as “the most unimaginative person on earth,” was confounded. Confounding his father became a lifelong project.

Before del Toro started school, his father won the Mexican national lottery. Federico built a Chrysler-dealership empire with the money, and moved the family into a white modernist mansion. Little Guillermo haunted it. He raised a gothic menagerie: hundreds of snakes, a crow, and white rats that he sometimes snuggled with in bed.•

Tags: Daniel Zalewsk, Guillermo del Toro

As the tragic final chapter of Natalie Wood’s life is reopened, here’s her 1966 What’s My Line appearance, with Peter Ustinov on the panel.

Tags: Natalie Wood, Peter Ustinov

Orson Welles defending himself, in 1965. You have to assume the interviewer had never seen Touch of Evil.

Tags: Orson Welles

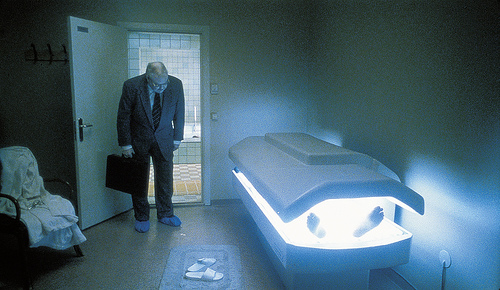

Roy Andersson’s millennial absurdist comedy, made amid the manufactured fears about Y2K, seems more suited to our desperate times. Not actually about the end of the world, but the end of the world as we know it, Songs From the Second Floor looks at the diminishing returns of the Industrial Revolution, the faltering of belief systems, the collapsing of structures that sustained us. As one character frankly states about the era’s closing: “The pyramids had their day…the steam engines had their day.”

In dark and deadpan scenes that are sometimes connected by storyline but always by a comically lethargic tone, sad-sacks of every type suffer through inescapable lives. Through these vignettes, we gradually learn that the stock market has collapsed, massive layoffs have occurred, religion has provided no succor and everyone is fleeing cities by car without anywhere to go, halted anyway by massive traffic jams.

Against this backdrop we see a misbegotten magician do a trick in which he saws a man in half, unintentionally making serrated metal meet flesh. A crucifix salesman, who has gone belly up, tosses his inventory into a garbage dump. A senile plutocrat–with a very questionable political past–sits in a crib like a baby. Even the ritual sacrifice of a child, as organized religion reverts to its primal, pagan origins, is done with a perfunctory and mechanical air. Everyone knows the jig is up but no one can quite stop shuffling their feet.

Against this backdrop we see a misbegotten magician do a trick in which he saws a man in half, unintentionally making serrated metal meet flesh. A crucifix salesman, who has gone belly up, tosses his inventory into a garbage dump. A senile plutocrat–with a very questionable political past–sits in a crib like a baby. Even the ritual sacrifice of a child, as organized religion reverts to its primal, pagan origins, is done with a perfunctory and mechanical air. Everyone knows the jig is up but no one can quite stop shuffling their feet.

Andersson, a veteran commercial director, used many of the same actors from his automobile ads in the film, and here he’s not selling internal combustion engines, but the demise of a society that can no longer survive on such contraptions. When one of his many hapless characters is cautioned that he must accept that a new dawn has arrived and changes will be drastic, he responds warily, “That will be a disaster for a lot of people.”•

Tags: Roy Andersson

Ilya Khrzhanovskiy’s 4, one of my favorite films of the aughts, was almost indescribably odd. Stranger still, is the follow-up, or the production of it, which has been filming for five years and counting in a Ukranian town, and resembles more a totalitarian state driven by the type of hubris that Herzog and Coppola brought to the jungle, than a mere movie. The opening of Michael Idov’s great GQ article, “The Movie Set That Ate Itself“:

“The rumors started seeping out of Ukraine about three years ago: A young Russian film director has holed up on the outskirts of Kharkov, a town of 1.4 million in the country’s east, making…something. A movie, sure, but not just that. If the gossip was to be believed, this was the most expansive, complicated, all-consuming film project ever attempted.

A steady stream of former extras and fired PAs talked of the shoot in terms usually reserved for survivalist camps. The director, Ilya Khrzhanovsky, was a madman who forced the crew to dress in Stalin-era clothes, fed them Soviet food out of cans and tins, and paid them in Soviet money. Others said the project was a cult and everyone involved worked for free. Khrzhanovsky had taken over all of Kharkov, they said, shutting down the airport. No, no, others insisted, the entire thing was a prison experiment, perhaps filmed surreptitiously by hidden cameras. Film critic Stanislav Zelvensky blogged that he expected ‘heads on spikes’ around the encampment.

I have ample time and incentive to rerun these snatches of gossip in my head as my rickety Saab prop plane makes its jittery approach to Kharkov. Another terrible minute later, it’s rolling down an overgrown airfield between rusting husks of Aeroflot planes grounded by the empire’s fall. The airport isn’t much, but at least it hasn’t been taken over by the film. And while my cab driver knows all about the shoot—the production borrowed his friend’s vintage car, he brags without prompting—he doesn’t seem to be in the director’s thrall or employ.

I’m about to write the rumors off as idle blog chatter when I get to the film’s compound itself and, again, find myself ready to believe anything. The set, seen from the outside, is an enormous wooden box jutting directly out of a three-story brick building that houses the film’s vast offices, workshops, and prop warehouses. The wardrobe department alone takes up the entire basement. Here, a pair of twins order me out of my clothes and into a 1950s three-piece suit complete with sock garters, pants that go up to the navel, a fedora, two bricklike brown shoes, an undershirt, and boxers. Black, itchy, and unspeakably ugly, the underwear is enough to trigger Proustian recall of the worst kind in anyone who’s spent any time in the USSR. (I lived in Latvia through high school.) Seventy years of quotidian misery held with one waistband.

The twins, Olya and Lena, see nothing unusual about this hazing ritual for a reporter who’s not going to appear in a single shot of the film—just like they see nothing unusual in the fact that the cameras haven’t rolled for more than a month. After all, the film, tentatively titled Dau, has been in production since 2006 and won’t wrap until 2012, if ever. But within the walls of the set, for the 300 people working on the project—including the fifty or so who live in costume, in character—there is no difference between ‘on’ and ‘off.'”

Tags: Ilya Khrzhanovskiy, Michael Idov

Peter Sellers goofing around during a rare talk-show appearances, 1970.

Sellers works broad with Dean Martin, 1973:

More Peter Sellers posts:

- Sellers stars in Being There. (1979)

Tags: Dean Martin, Peter Sellers

That happily married (and remarried) couple, Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, profiled on 60 Minutes, 1970.

Their greatest joint film effort, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, as performed by fast-talking commercial pitchmen (and women), SCTV, 1980:

The great Robert Mitchum refuses to terrify Dick Cavett, 1971.

Tags: Dick Cavett, Robert Mitchum

Released at a time when tech nerds were emerging from their garages and dorms to reengineer the world as we watched with shock and awe, David Cronenberg’s 1981 sci-fi mindblower about bioengineered telepaths, Scanners, could be read as an analogue to the rise of the machines and those who built them. Scanners and digital revolutionaries who began their ascent in the late 1970s can be described alike: born with special gifts, could see the future before others, desired to upset the accepted order and create a new society in which the mind and its powers would be predominant. “They’re pathetic social misfits,” says one character of the tortured titular telepaths but might as well be describing those responsible for technology’s migration from the monolith to the individual. “They want to destroy the society that created them.” And so they did, more or less.

In Cronenberg’s world, Scanners are misbegotten men and women who were born telepaths with terrible talents. They cannot only read your mind but can also use mere concentration to blow up your brain. In order to keep them from using this talent, Scanners are monitored and sometimes hunted. It seems that their strange skills are the result of their pregnant mothers being prescribed an experimental tranquilizer that was discontinued in the 1940s after a brief trial run. While the drug soon disappeared, the children have grown up with extraordinary powers, unbeknownst to most of the world.

The scientist who created the drug, Dr. Paul Ruth (Patrick McGoohan), a pioneering biochemist with a patchy past, has made it his life’s work to monitor the Scanners for the ConSec corporation. Ruth reintroduces into society a Scanner named Cameron Vale (Stephen Lack), who he has kept “on ice,” to glean information about the machinations of a fellow Scanner, Darryl Revok (Michael Ironside). The latter has apparently hatched a plan with a confedrate inside ConSec to create a new breed of Scanners that he can use as his army. Cameron and Revok, who have some sort of mysterious link to one another, engage in a battle of terrifying, combustible wills.

Changing the world, or at least the way we interact with it and one another, requires getting others to see reality in a whole new way, whether you’re hoping to grow scanners or consumers, a fact which has become ever clearer as we now live in a world in which a small band of Silicon Valley superstars have commandeered the means of communication. As Revok says, while sounding not unlike a titan of technology preparing for an IPO: “We’ll bring the normals to their knees. We’ll have an empire so brilliant, so glorious that it will be the envy of the whole planet.”•

Tags: David Cronenberg, Michael Ironside, Patruck McGoohan, Stephen Lack

I’d be really happy if New York Times film critics A.O. Scott and Manohla Dargis were awarded Pulitzers in the same year. The quantity and quality of their writing is pretty stunning. The pair teamed up for a discussion about the legendary Pauline Kael, an influential scribe in her day (and ours, still) who was a thorny character, to say the least. An excerpt from Dargis about the erstwhile celebrity status of film critics:

“If she still casts a shadow it’s less because of her ideas, pugilistic writing style, ethical lapses and cruelties (and not merely in her reviews), and more because she was writing at a time when movies, their critics and, by extension, the mainstream media had a greater hold on American culture than they do now. In his book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls Peter Biskind relates a story from the mid-’80s when Kael turned to Richard Schickel at a meeting of film critics and said, ‘It isn’t any fun anymore.’ Mr. Schickel asked her why and she replied: ‘Remember how it was in the ’60s and ’70s, when movies were hot, whenwe were hot? Movies seemed to matter.’ The thing is, they did matter and still do, just differently.

One thing that changed was the role of the film critic, who by the mid-’80s no longer had to persuade a skeptical, sometimes hostile general audience that it was necessary to take movies seriously. In 1967, though, Kael had to explain in The New Yorker why and how Bonnie and Clyde was important (and in 9,000 words!). She was part of a critical vanguard spreading the new film gospel in reviews, books, talk shows, everywhere. They were true pop cultural figures. The critic Judith Crist even shilled for a feminine-hygiene spray. She later said that she did the ad because Richard Avedon took the photos, she could write most of the text and the ad would reach more than 100 million readers. Also: she got $5,000.”

•••••••••

Kael and other film critics were famous enough in 1977 to be spoofed by SCTV:

Tags: A.O. Scott, Judith Crist, Manohla Dargis, Pauline Kael

The sci-fi thriller Limitless asks questions about the type of neutrino-speed performance enhancement for humans that seems possible in the not-too-distant future, but it doesn’t ask the best and most important ones. Neil Burger’s movie is concerned with the complications that arise when a wonder drug that bestows superhuman abilities turns out to be less than wonderful, attended by side effects, glitches and downsides. The better questions to ask are: What will we do when such pills and (microchips) have no side effects at all? In which direction will we head when all signs are pointing up, and we can get there through no effort of our own? Will we see a pain-free ability to realize our human potential as something less than human?

Eddie (Bradley Cooper) is a depressed novelist with writer’s block and a broken heart. Kicked to the curb by his disappointed girlfriend (Abbie Cornish), he drinks and frets and dodges anyone he owes money to. But then the previously married author has a chance encounter with his erstwhile brother-in-law (Johnny Whitworth), a former coke dealer who claims to now be pushing FDA-approved wonder drugs for Big Pharma. He hands Eddie a bright, clear pill not yet available to the public, and it quickly changes the writer’s life. Eddie not only finishes his stalled novel in four days, but learns languages in a matter of minutes and becomes a wealthy titan on Wall Street. The world is suddenly wide open.

But there are extreme side effects for those who try to taper off, as Eddie learns when his stash begins to grow low. But what if the supply was as limitless as the capacity it allowed? When we have the ability to improve neurons, nerves and muscles at a whim, will the choice be obvious? Will some decide to stay behind? Will the change be so gradual that we won’t really notice the transformation? Those are the questions we should be asking.•

Tags: Abbie Cornish, Bradley Cooper, Johnny Whitworth, Neil Burger

Rare interview with the incredible Peter Sellers, who hated appearing out of character and seldom did chat shows. From 1974, a decade after an experimental pacemaker saved his life, and five years before he starred in Being There.

Tags: Michael Parkinson, Peter Sellers

In the aftermath of the 1960s tumult, social networks arose, but of a non-virtual sort. People gathered in circles, discussed their feelings and tried to come to a point where true intimacy could exist with their spouses and with others. Paul Mazursky’s comedy of manners, Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, is interested in both spouses and the others, studying a pair of married couples racing to the front lines of the sexual revolution before the hand-to-hand ends.

Middle-aged journalist Bob (Robert Culp) and his beautiful wife, Carol (Natalie Wood), leave their kid behind to attend just such a weekend retreat. They’re ostensibly there at this groovy 24-hour crash course in intimacy so that Bob can write an article, but his long hair and mod clothes make it clear that Bob isn’t interested in growing old before he’s had a chance to be young.

Bob and Carol both emerge greatly changed, ready to open their minds and blouses and pants. Bob soon has an affair, and is taken aback when his suddenly non-judgemental wife doesn’t mind. Bob has a much tougher time dealing with his emotions when Carol beds her tennis pro, Horst. But soon he and Horst are drinking and laughing together, and Bob feels liberated from feelings of jealousy. But the acolyte swingers have a difficult time explaining their moral shift to their best friends, the uptight marrieds Ted (Elliot Gould) and Alice (Dyan Cannon). Ted and Alice are revolted—and perhaps just a wee bit curious.

When the four friends head to Atlantic City together for a weekend of gambling, they’re soon weighing whether or not to get their group on. Or as one member of the quartet puts it: “First we’ll have an orgy, and then we’ll go see Tony Bennett.”

Mazursky tries to find a balance in the concluding scenes, acknowledging the need to break down walls, but perhaps not every last one. An utter lack of boundaries can’t work, but are we any closer now, with all our connectedness, to finding a middle ground? What are we connected to? An icon? An identity? A “friend”? It brings to mind something uttered in the film’s consciousness-raising circle: “You chat…but you don’t really look at each other.”•

Tags: Dyan Cannon, Elliot Gould, Natalie Wood, Paul Mazursky, Robert Culp

A 60 Minutes report from 1978 about the burgeoning business of movie piracy.

Unmentioned in my post on Meek’s Cutoff was that two of its cast members are the great young actors Paul Dano and Zoe Kazan (an off-screen couple as well). Dano came to notice in Little Miss Sunshine and gave a mind-blowing performance in There Will Be Blood. He was the subject of a short profile by Melena Ryzik in the New York Times Magazine in 2009. An excerpt:

“Mr. Dano grew up in Manhattan and Wilton, Conn. He made his Broadway debut at 12 in Inherit the Wind, with George C. Scott and Charles Durning, and a few years later appeared as a troubled teenager preyed upon by a pedophile (played by Brian Cox) in the film L.I.E. Despite the steady work, Mr. Dano wasn’t thinking about building a career. Acting was just fun, he said, on a par with other after-school activities, like basketball.

Little Miss Sunshine, released in 2006, was a turning point. The story of a misfit family’s road trip, it became the toast of Sundance and won two Oscars. Mr. Dano’s character, a misfit among misfits, doesn’t speak for most of the movie, yet manages to be a focal point in a cast including Alan Arkin and Steve Carell.

Mr. Dano auditioned for it two years before it was made. ‘Sometimes when people don’t have a line, they want to mime the line or communicate too much, but he was good at holding it all in,’ Ms. Faris said. ‘His silence was so much more intimidating, in a way, than other actors.'”

••••••••••

“The devil is in your hands and I will suck it out”:

Tags: Melena Ryzik, Paul Dano, Zoe Kazan

Unlike her Dick Cavett interview from the same year, in which she largely seemed bitter and hard, Lucille Ball is her bright self in this 1974 chat with Phil Donahue.

Tags: Lucille Ball, Phil Donahue

In writing about the new Steven Soderbergh film, Contagion, Alex Tabarrok of the Marginal Revolution points out an unintended benefit of the war against bio-terrorism that arose after 9/11:

“That is exactly right. Fortunately, under the umbrella of bio-terrorism, we have invested in the public health system by building more bio-safety level 3 and 4 laboratories including the latest BSL3 at George Mason University, we have expanded the CDC and built up epidemic centers at the WHO and elsewhere and we have improved some local public health centers. Most importantly, a network of experts at the department of defense, the CDC, universities and private firms has been created. All of this has increased the speed at which we can respond to a natural or unnatural pandemic.

In 2009, as H1N1 was spreading rapidly, the Pentagon’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency asked Professor Ian Lipkin, the director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, to sequence the virus. Working non-stop and updating other geneticists hourly, Lipkin and his team were able to sequence the virus in 31 hours. (Professor Ian Sussman, played in the movie by Elliott Gould, is based on Lipkin.) As the movie explains, however, sequencing a virus is only the first step to developing a drug or vaccine and the latter steps are more difficult and more filled with paperwork and delay. In the case of H1N1 it took months to even get going on animal studies, in part because of the massive amount of paperwork that is required to work on animals.”

Tags: Alex Tabrrok, Elliott Gould, Ian Lipkin, Ian Sussman, Steven Soderbergh

As Hollywood’s studio system collapsed in the 1960s and the anti-hero indie Easy Rider showed a new path to riches, mavericks like Dennis Hooper could do anything they wanted. That freedom, of course, wasn’t the best thing for Hopper’s health or sanity. One of the least self-lacerating things he did during that era was to read a Rudyard Kipling poem for Johnny Cash in 1970.

More Dennis Hopper posts:

Tags: Dennis Hopper, Johnny Cash

“We’ve come to a terrible place,” says a member of a lost and increasingly desperate 1845 traveling party on the Oregon Trail, in Kelley Reichardt’s understated 2010 drama. A portrait of pioneers who have a date with Manifest Destiny, the film follows a blustery guide and several clans as they traverse the Northwest looking for America’s future, having been sold on stories of plenty, but instead finding a cruel earth that dispenses wealth or woe on a whim.

Gruff guide Stephen Meek (Bruce Greenwood) talks big about the gold in them thar hills, but the three families who’ve paid him to deliver them to some semblance of utopia—the Tetherows, the Whites and the Gatelys–are low on water and patience. They’ve been wandering the desert for weeks and have come no closer to their original destination. Lost in a strange land that is not yet American, the party puts up with all manners of privations as they continue on their road to nowhere. When Meek captures an Indian, Emily Tetherow (Michelle Williams) believes that they may be better off allowing the stranger (Rod Rondeaux) to lead them than their puzzled pathfinder, although there is the chance they will be delivered into an ambush. But one thing can be scarier than this choice: the realization that there truly is no choice to be made, that the forks in the road will decide their fate regardless of who is at the head of the line.

It’s easy to forget in our insta-societry that for much of our country’s history pioneering meant heading somewhere and then waiting for the future to arrive. Until civilization took root, settlers were prone to the conditions and dependent on luck as well as grit. But the pioneer spirit has come to mean something different to us–not waiting for the future to arrive, but trying to keep up with one that arrives with stunning regularity. That’s where we are now, pioneers all, willing or not.•

Tags: Bruce Greenwood, Kelly Reichardt, Michelle Williams, Rod Rondeaux

Dennis Hopper interviewed by David Brenner in 1986, just as David Lynch released his masterpiece, Blue Velvet, which would lead to a career renaissance for the actor. Hopper was married for a few years to Daria Halprin.

Tags: Daria Halprin, David Brenner, Deniis Hopper