A volcano the intensity of the one in 1815 that disrupted the world will occur again at some point, but even though there is more to destroy now, the impact by some measures–on agriculture, say–will probably not be as great today. From the Economist (by way of the Browser):

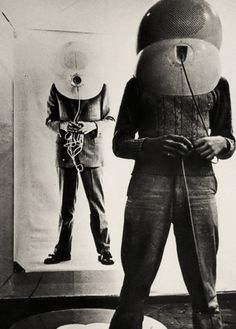

IF ALIENS had been watching the Earth during 1815 the chances are they would not have noticed the cannon fire of Waterloo, let alone the final decisions of the Congress of Vienna or the birth of Otto von Bismark. Such things loom larger in history books than they do in astronomical observations. What they might have noticed instead was that, as the year went on, the planet in their telescopes began to reflect a little more sunlight. And if their eyes or instruments had been sensitive to the infrared, as well as to visible light, the curious aliens would have noticed that as the planet brightened, its surface cooled. …

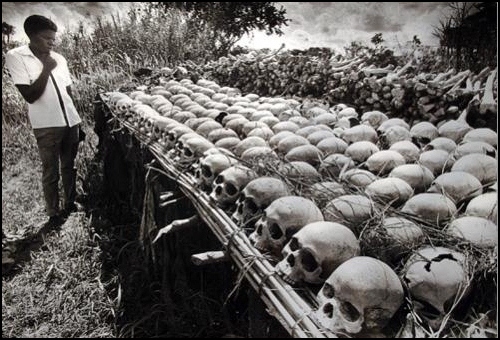

In his book Eruptions that Shook the World, Clive Oppenheimer, a volcanologist at Cambridge University, puts the number killed by the ash flows, the tsunamis and the starvation that followed them in Indonesia at 60,000-120,000. That alone would make Tambora’s eruption the deadliest on record. But the eruption did not restrict its impact to the areas pummelled by waves and smothered by ash.

When the sulphur hits the stratosphere

The year after the eruption clothes froze to washing lines in the New England summer and glaciers surged down Alpine valleys at an alarming rate. Countless thousands starved in China’s Yunnan province and typhus spread across Europe. Grain was in such short supply in Britain that the Corn Laws were suspended and a poetic coterie succumbing to cabin fever on the shores of Lake Geneva dreamed up nightmares that would haunt the imagination for centuries to come. And no one knew that the common cause of all these things was a ruined mountain in a far-off sea.

While lesser eruptions since then have had measurable effects on the climate across the planet, none has been large enough to disrupt lives to anything like the same worldwide extent. It may be that no eruption ever does so again. But if that turns out to be the case, it will be because the human world has changed, not because volcanoes have. The future will undoubtedly see eruptions as large as Tambora, and a good bit larger still.•