As costs and chips shrunk and things formerly known as supercomputers slipped into our pockets, space exploration ceased being a top-down affair possible only for governments. Perhaps a corporation like SpaceX will best NASA in a rush to Mars, and maybe a different free-market concern will establish a city in a moon crater. At the very least, satellites will become merely expensive toys–and then inexpensive ones. As 3D printers continue to improve, the stratosphere will grow more clogged. In this new normal, should there be formalized rules of engagement that all must abide?

That’s the prescription suggested in “The Democratization of Space,” a new Foreign Affairs piece by Dave Baiocchi and William Welser IV, which calls for a 21st-century version of the Outer Space Treaty to address a raft of issues, including the situational awareness of the growing number of satellites launched. An excerpt:

IN 1967, the United States, the Soviet Union, and many other countries signed the Outer Space Treaty, which set up a framework for managing activities in space—usually defined as beginning 62 miles above sea level. The treaty established national governments as the parties responsible for governing space, a principle that remains in place today.

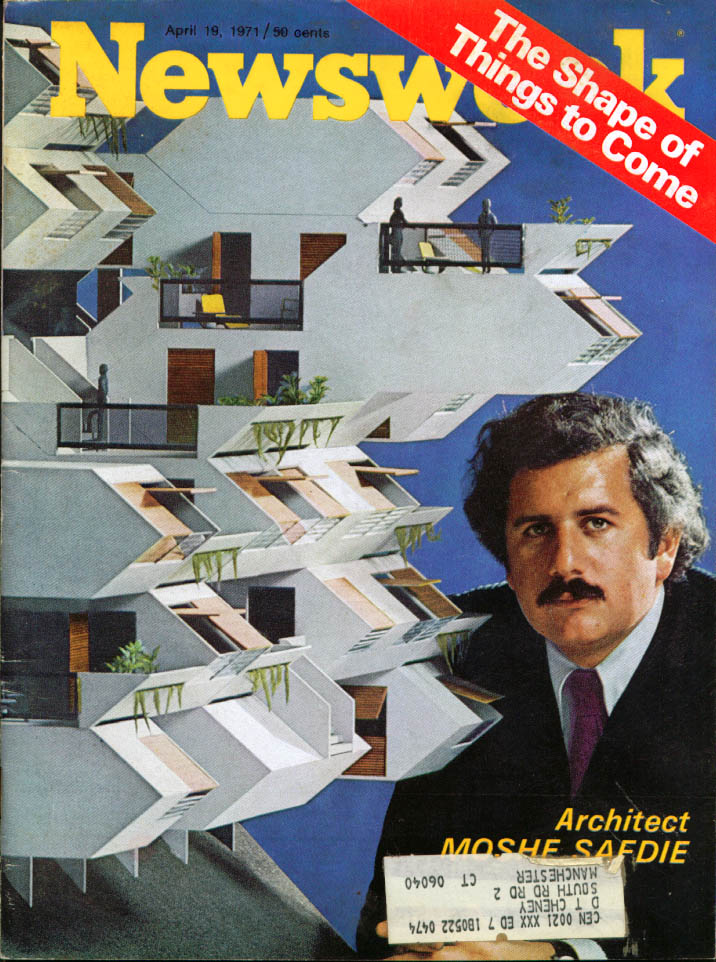

Half a century later, however, building a basic satellite is no longer considered rocket science. Thanks to the availability of small, energy-efficient computers, innovative manufacturing processes, and new business models for launching rockets, it has become easier than ever to launch a space mission. These advances have opened up space to a crowd of new actors, from developing countries to small start-ups. In other words, a new space race has begun, and in this one, nation-states are not the only participants. Unlike in the first space race, the challenge in this one will not be technical; it will be figuring out how to regulate this welter of new activity.

FREE-FOR-ALL

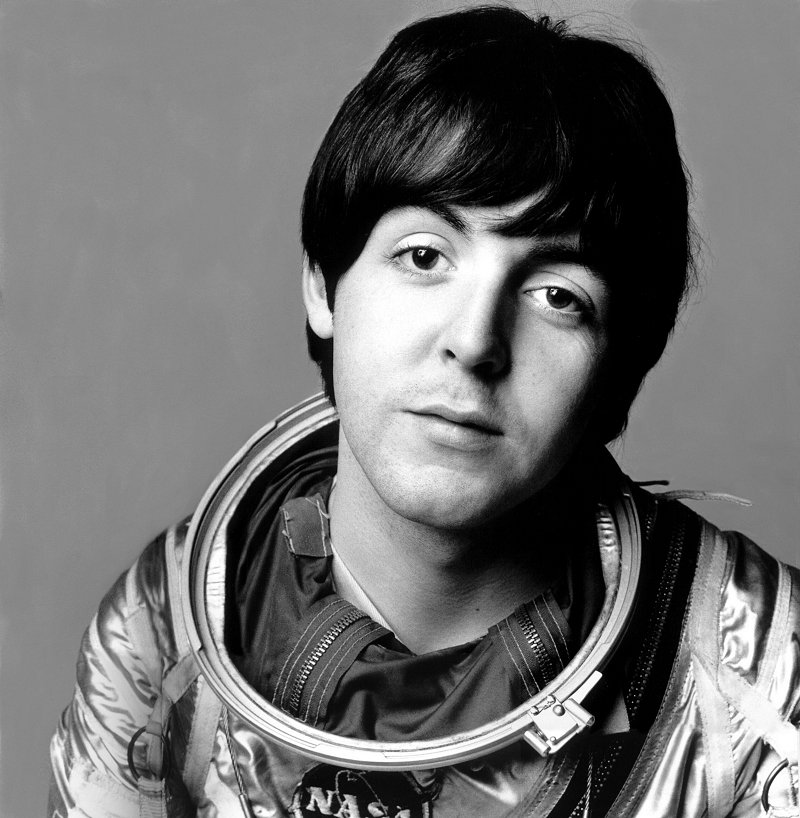

Computing gets much of the credit for lowering the barriers to entry to space.•