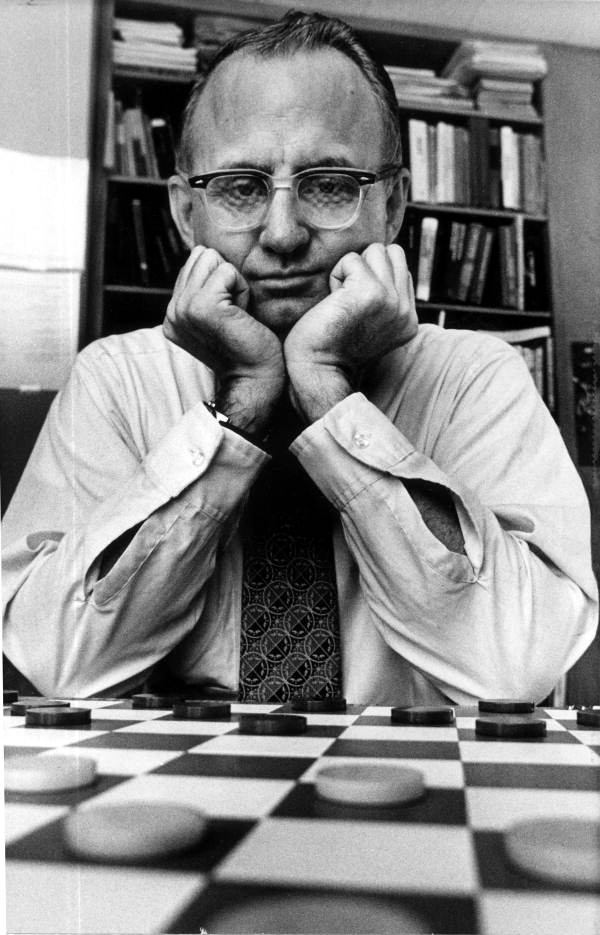

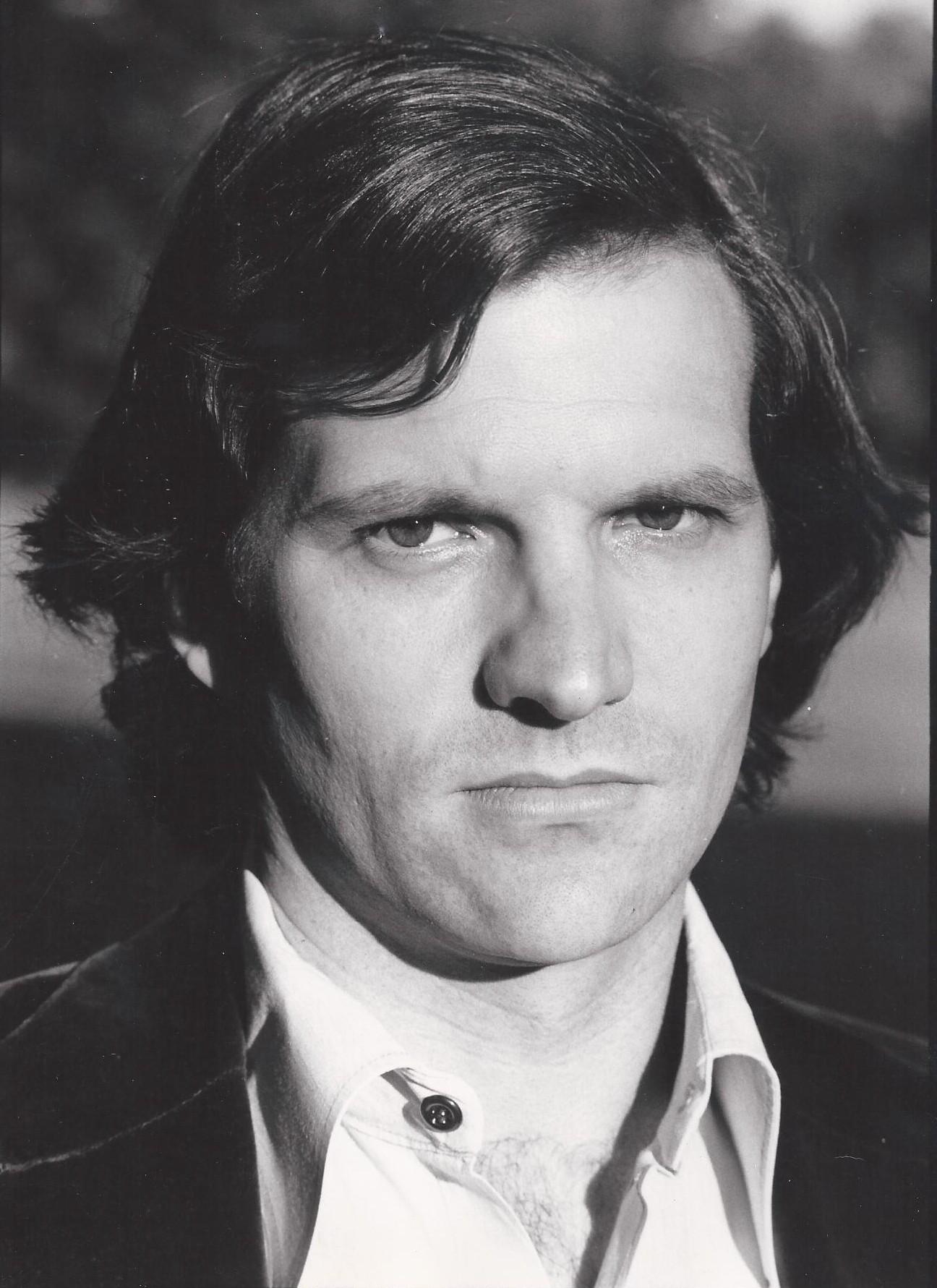

The chess world–and the human race itself, by extension–was famously rocked in 1997 when Garry Kasparov was spooked and conquered by Deep Blue. Not as well known: This rise of the machines had been presaged five years earlier in the less complicated and revered game of checkers when the all-but-undefeatable champion, the mathematician Marion Tinsley, was lucky to escape with a victory after losing twice in his series against an AI known as Chinook, designed by Canadian computer science professor Jonathan Schaefer.

From Gary Belsky’s 1992 Sports Illustrated report:

In the odd world of checkers—a 5,000-year-old game that almost everyone knows how to play but only a few thousand people compete in seriously—Tinsley is a legend. “Dr. Tinsley has taken the game beyond what anybody else ever conceived,” says Charles Walker, the founder and director of the International Checkers Hall of Fame, in Petal, Miss. Tinsley’s edge is his unparalleled knowledge of the game, which originated in Egypt but assumed its modern form some 700 years ago in Scotland. Holder of a doctorate from Ohio State in the mathematical discipline of combinatorial analysis, Tinsley has a better-than-computer-like grasp of the 500 billion billion or so possible moves in a checkers game, an understanding that allows him to see 30 moves ahead, as opposed to the 24-move prescience of Chinook. “I’ve got a better programmer,” he explains. “God.”

Tinsley, who is a lay preacher in the Disciples of Christ church, was born in Ironton, Ohio, to a schoolteacher and a farmer turned sheriff. The boy was reading and memorizing poetry by the age of four. But the precocious youth, who skipped four of his first eight grades, was confounded by elementary school mathematics until he discovered geometry. His family was then living in Columbus, and one day, while researching a math problem in the library at nearby Ohio State, he came across several books about checkers. He studied them, hoping to silence an elderly woman who boarded with his family and who let loose a grating cackle every time she bested him in a game. “I had visions of beating Mrs. Kershaw,” Tinsley recalls.

He never did—Mrs. Kershaw moved away before he mastered checkers—but Tinsley did win the national championship in 1948 at age 21. He won the world title several years later, in 1955, by defeating Walter Hellman of Gary, Ind. Defending his title successfully in 1958, he retired from competition to devote himself to teaching and preaching. After 11 years at Florida State in Tallahassee, he moved across town to Florida A&M, in part because he saw teaching at the predominantly black school as an extension of the preaching he did at the predominantly black St. Augustine Street Church of Christ in Tallahassee. “I had thought of going to Africa as a self-supporting missionary,’ ” he says, “until a sharp-tongued sister pointed out to me that most people who wanted to help blacks in Africa wouldn’t even talk to blacks in America.”

It wasn’t until 1970 that Tinsley was coaxed back into competition by Don Lafferty, one of the many checkers devotees who still make pilgrimages to his home in Tallahassee. He won the U.S. championship that year, and in 1975 he regained the world title from Hellman, as it now seems, for good. Despite Tinsley’s long retirement and Hellman’s having officially held the title during that time, checkers cognoscenti view Tinsley’s championship reign as continuous. “No one presumed to think they could beat him,” says Walker. “When he loses one game, it is an event.”

Small wonder that the 50 or so spectators who gathered each day in London to watch Tinsley’s title defense were stunned when Tinsley found himself down two games to one after 14 games with Chinook. Tinsley, who was hospitalized with phlebitis in Florida after the tournament, blames grueling games and jet lag for the sleeplessness that left him exhausted during the first week of play. “A London fog rolled in on me, and I made mistakes,” he says. The fog lifted in the 18th game. In tournament checkers each player must make 20 moves in an hour. Inexplicably, Chinook froze 27 minutes into the first hour of the 18th game and neither Schaeffer nor his three assistants could thaw out the program. They resigned the game to even the match at 2—all. “I think Dr. Tinsley viewed it as divine intervention,” Schaeffer says ruefully.

The following day, Sunday, Tinsley went to church, and he returned on Monday, in Schaeffer’s eyes, “revitalized.” He won the 25th game two days later, and after 13 more draws, he got his fourth victory, winning the championship in the 39th game. Tinsley was characteristically humble afterward, crediting God with his victory. He said that he was looking forward to beating Chinook again when they rekindle their man-versus-machine rivalry next August outside London.

Eventually, though, Tinsley will almost certainly fall to the Canadian computer. Schaeffer believes that checkers, like tick-tacktoe, is “solvable”—that is, that it can be played perfectly, so every game ends in a draw at worst. Already Chinook has in its memory every outcome possible with seven or fewer pieces on the board. Within the decade, Schaeffer says, the computer will know how the game will turn out even before it begins. Until then Tinsley expects no serious human challenge. “I’d be surprised if somebody could actually beat me,” he says mildly. “I really hate to lose.”•

A 1994 rematch between Tinsley and Chinook was halted after six games when the champ took ill. Subsequently diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, Tinsley died the following year.

_________________________

At the 16:30 mark, Tinsley appears on a 1957 edition of What’s My Line?