The writer Calum Chace, an all-around interesting thinker, is conducting a Reddit AMA based on his new book, The Economic Singularity, which sees a future–and not such a far-flung one–when human labor is a thing of the past. It’s certainly possible since constantly improving technology could make fleets of cars driverless and factories workerless. In fact, there’s no reason why they can’t also be ownerless.

What happens then? How do we reconcile a free-market society with an automated one? In the long run, it could be a great victory for humanity, but getting from here to there will be bumpy. A few exchanges follow.

Question:

So it seems to me that most of the benefit of capitalism for working-class people come from jobs. Companies need a workforce, and are willing to pay for it. So a lot of the profit gets spread around to a lot of people.

If a few companies could break this model on a large scale, by leveraging automation to allow a relatively small core group of employees to operate a national or international corporation, then that would force everyone to do it in order to stay competitive.

I’m assuming that this is some of what you’re talking about in the book (just guessing from the title and an amazon summary).

I could see the first fully (>98%) automated company making waves in a decade or two. People on /r/futorology like to wax utopian, but a company with <100 employees and billions in automated infrastructure isn’t going to allow themselves to be operated for the public good. The product might be cheap, but it’s not free, and that company is no longer employing enough people to matter.

They’ll have a global reach (through subcontracted shipping companies) coupled with automated vehicles that don’t need to sleep or visit family. They can legally exist in whichever country is cheapest tax-wise, and still destroy the competition on the other side of the globe.

So, lots of rambling. But that’s my question, basically.In your opinion, what might the replacement for capitalism look like?

Calum Chace:

Yes, I think you’ve identified exactly the first stage of the argument. Intelligent machines are probably going to render most of us unemployable.

So how shall we all live? The answer, initially at least, will be some form of Universal Basic Income (UBI) which is often discussed here and at a sister Reddit page specifically on the subject. UBI will have to be paid for by taxes, and that raises some tricky questions about how the rich people who pay the taxes are going to respond.

I am fundamentally optimistic. The people who are going to be richest are those who own the AI, since that will generate much of the value throughout the economy. The likes of Larry Page, Sergei Brin, Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates etc etc don’t seem to me to be primarily motivated by money, but by an excitement about the future and a desire to see it arrive sooner.

So I don’t think they will want the rest of us to starve. The mechanism by which UBI is phased in, and how it pans out across international boundaries are going to take a lot of detailed planning. Which we haven’t started yet.

Question:

I also think people are underestimating VR & crowdsourcing’s role.

If VR makes things like microtasking more attractive to do and enables the microtaskers (crowd-workers) to do more, then flexwork/ gig-work might become even more popular. I have an ebook that I’m finishing up now that explores this a little bit (& even ties it to robotics).

Do you have any guesses for VR and the future of work?

Calum Chace:

Yes, I talk about the gig economy (microtasking) in my book. A report by PwC says that 7% of US adults are already engaged in it. I’m not sure whether the experience is so great for most of them at the moment, though. Are they “micro-entrepreneurs” or “instaserfs” – members of a new “precariat”? Either way, it will probably get bigger.

It’s hard to avoid waxing lyrical about the potential impact of VR. Oculus Rift has made nothing like the splash since its launch this year a lot of people (including me) expected it to, but it’s probably just obeying Amara’s Law, that we tend to over-estimate the effect of a technology in the short run and under-estimate the effect in the long run.

In that long run I can well imagine VR bringing about the long-awaited death of geography, but it’s probably going to take a while yet. Meanwhile, I’m not sure it will have that much impact on overall levels of employment, other than adding some because of all the virtual experiences that need to be created.

Question:

I think the outcome can be wonderful: a world of radical abundance.

Calum Chace:

I very much agree with you there, I think that all (7 billion + of us globally) are going to be vastly richer from all of this.

For example, when AI can administer the expertise of top doctors & consultants to everyone on the planet for pennies, this is wealth unlike humanity has ever known before.

I wonder though, on the road to this future, are we in for some quite chaotic breaks from the past.

Exactly, and the sooner we start thinking seriously about where we want to get to and how best to get there, the more likely we are to make the journey successfully.

I think the more people who are aware of what is coming, the better. I’m encouraged by the remarkable sea-change in awareness of AI progress that has already occurred. The publication of Bostrom’s Superintelligence led to high-profile comments by the three wise men (Hawking, Musk and Gates) and the publication of Ford’s Rise of the Robots was another seminal moment.

Like a lot of people here, I’ve been talking about the huge importance of AI to anyone who would listen for years and years. I got a lot of benign virtual pats on the head. Now people are listening.

Self-driving cars will probably be the canary in the coal mine. Once they are common sights, people won’t be able to avoid thinking seriously about what is coming.

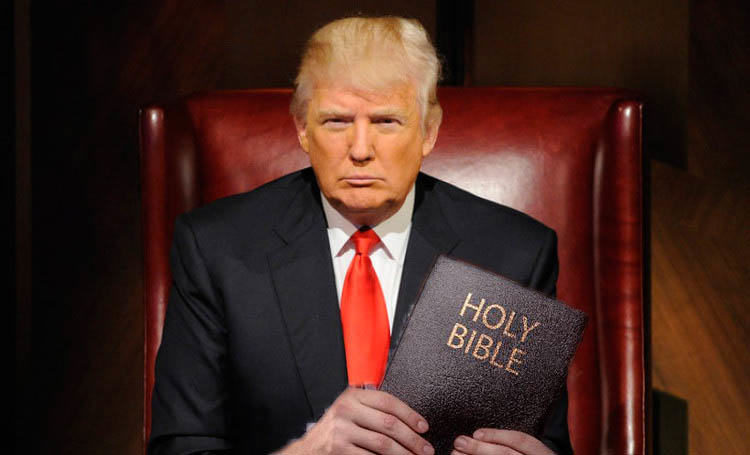

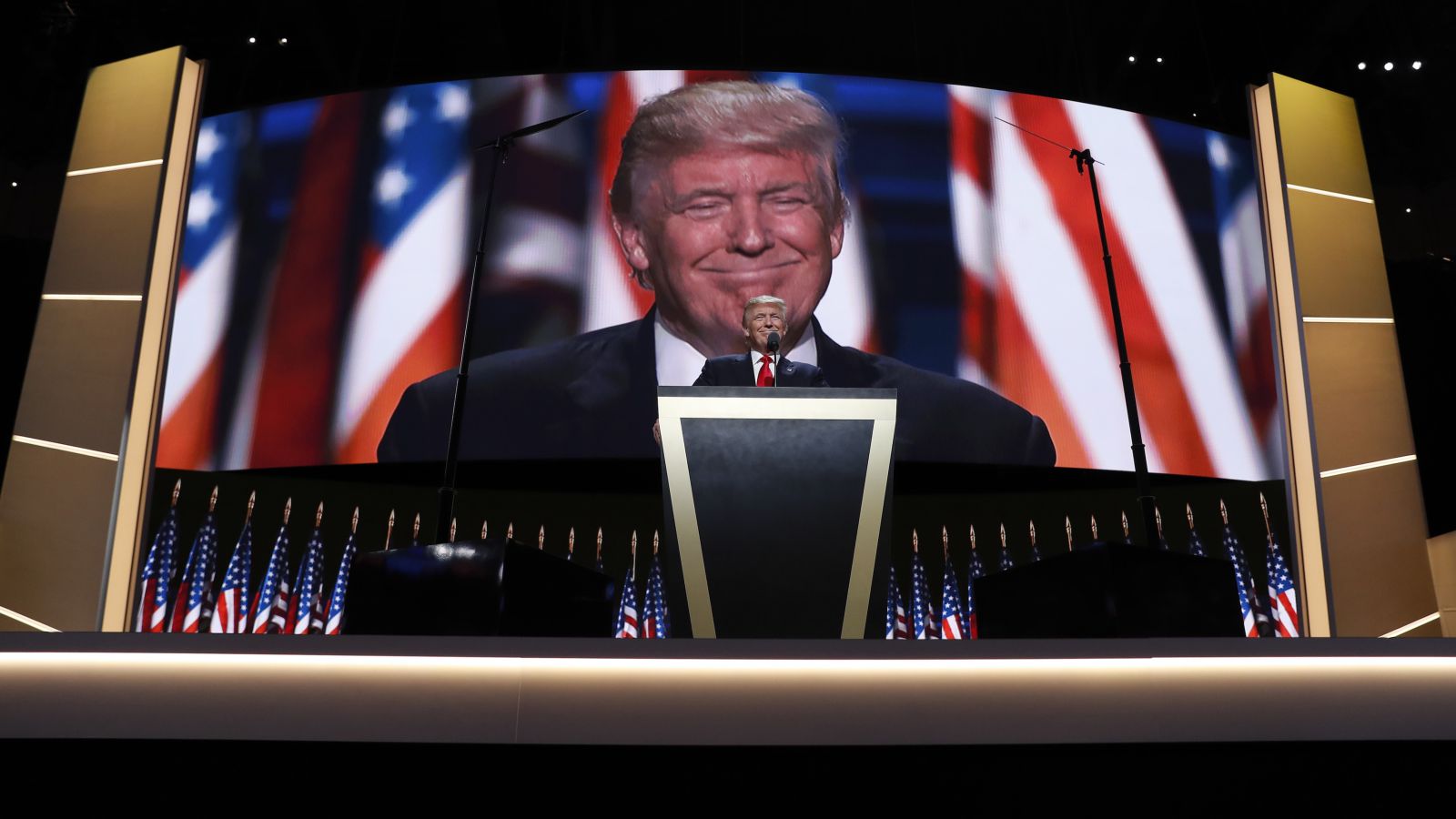

But we need a positive narrative about the good things that can happen so that the response isn’t panic, or a rush into the embrace of the next populist demagogue who happens along.•