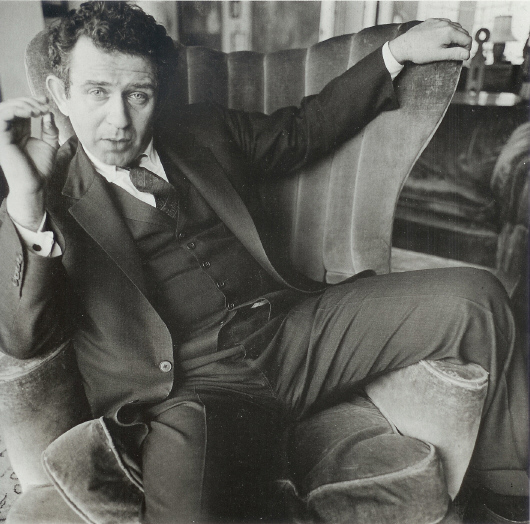

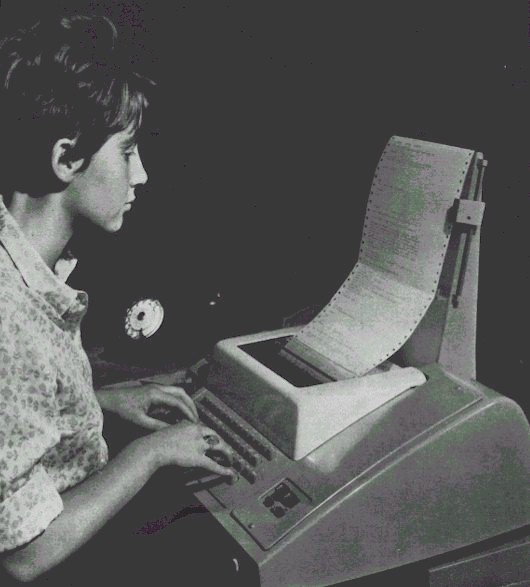

At the Financial Times, Simon Schama presents a portrait of Yoko Ono at 79. An excerpt about the bold performance art she made before she was a Beatle bride, which showed a really good understanding of neuroscience:

“In a cold-water apartment on Chambers Street, New York, she gave a series of performances and concerts in which minimalist ‘instructions’ and transient experiences replaced the static, monumental pretensions of framed pictures. The prompted eye and the receptive brain made the pictures instead. The technique was lovely, liberating and genuinely innovative. ‘I thought art should be like science, always discovering things afresh, and I wanted to be Madame Curie.’

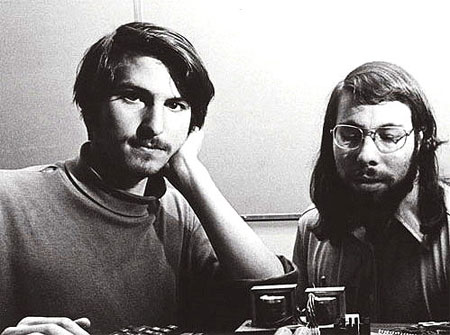

So when she and Lennon had their momentous encounter at Indica in 1966, Ono was already established as an avant-garde conceptual artist. She insists she really had no idea who he was or what he did. ‘I just saw this rather attractive guy who seemed to be taking my work very seriously.’ Of pop music she knew nothing, ‘not even of Elvis Presley; just maybe some jazz.’ Of what was about to hit them both out there in Beatlemania land she had no clue. ‘I was naïve. We both were … we thought that it was going to be really great.’ It wasn’t. ‘My work totally disappeared and John, with all that power he had, was going to go down too.’ She falls quiet for a moment; a flicker of sadness clouding the wide, expressively sunny face. ‘I feel very badly if maybe I was the cause of it.'” (Thanks Browser.)

••••••••••

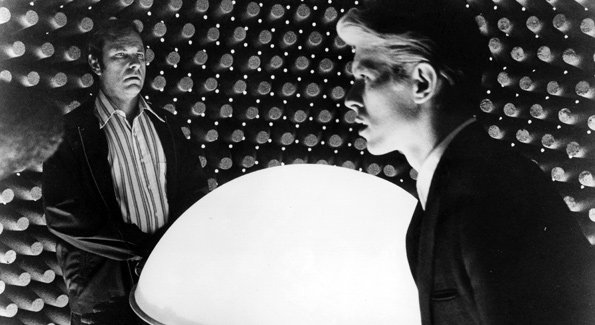

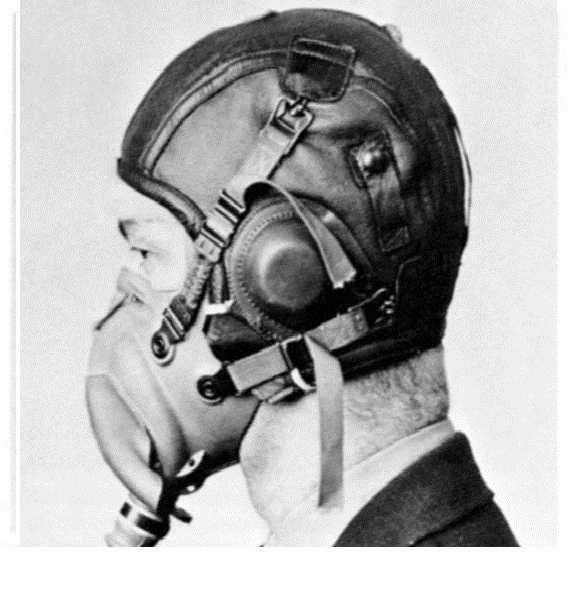

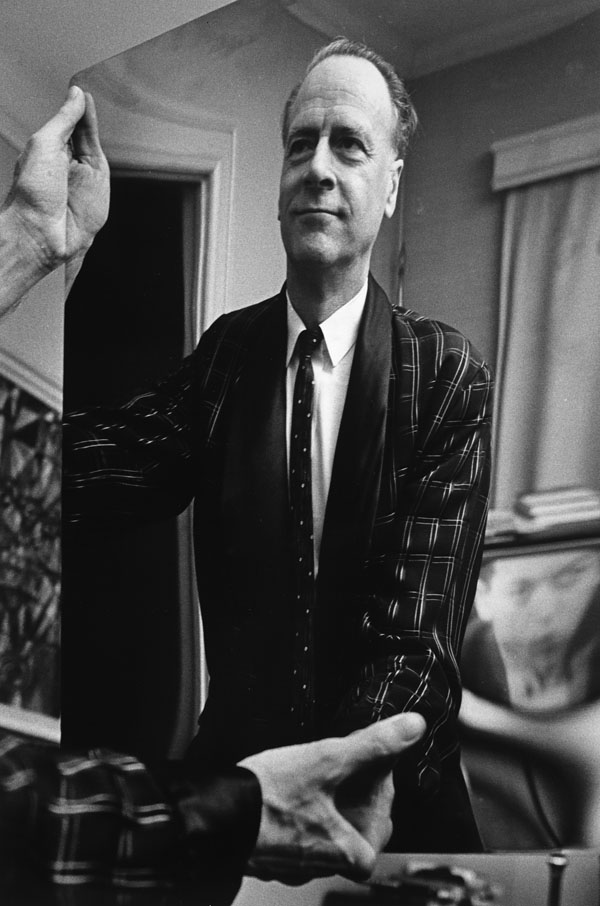

“The Cut Piece,” 1965: