Thinking about phone booths reminds me of this image from the end of the 1930s. (It’s a part of the Larry Zim Collection at the Smithsonian.) It is simply captioned: “Two couples in a futuristic family telephone booth at the New York World’s Fair in 1939.” Some people thought that technology was going to get bigger, more expansive, but others knew we would end up putting everything on the head of a pin.

You are currently browsing the archive for the Excerpts category.

Telephone booths, those pre-mobile totems to obsolesence, are being repurposed in NYC. From Ryan Kim at Gigaom:

“Payphones, those relics of the pre-cellphone era, may just get a new lease on life in New York. The city is testing a pilot program in which it installs free Wi-Fi on select payphone kiosks.

The hotspots are initially coming to ten payphones in three of the boroughs and will be open to the public to access for free. Users just agree to the terms, visit the city’s tourism website and then they’re up and running. Currently, there are no ads on the service, but there could be in the future.”

Tags: Ryan Kim

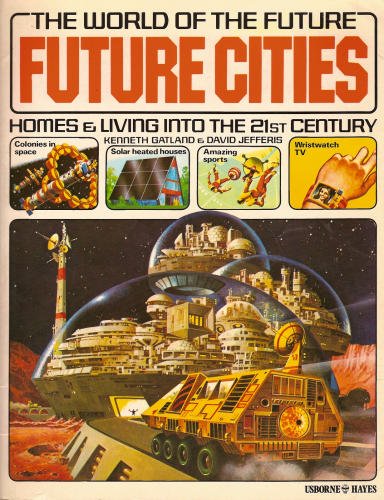

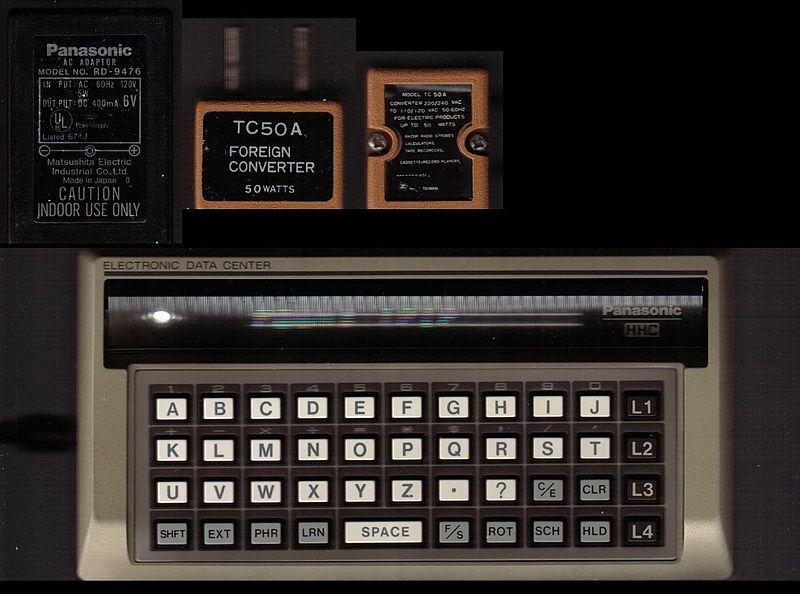

Xeni Jardin at Boing Boing put up a fun post about Future Cities: Homes and Living into the 21st Century, a 1979 children’s book by Kenneth William Gatland and David Jefferis. It envisioned a brave new world, some of which has come to pass, though not yet the domestic robot that rolls into the living room with drinks. From the section “Computers in the Home”:

“The same computer revolution which has resulted in calculators and digital watches could, through the 1980s and ’90s, revolutionize people’s living habits.

Television is changing from a box to stare at into a useful two-way tool. Electronic newspapers are already available–pushing the button on a handset lets you read ‘pages’ of news, weather puzzles and quizzes.

TV-telephones should be a practical reality by the mid 1980s. Xerox copying over the telephone already exists. Combining the two could result in millions of office workers being able to work at home if they wish. There is little need to work in a central office if a computer can store records, copiers can send information from place to place and people can talk on TV-telephones.”

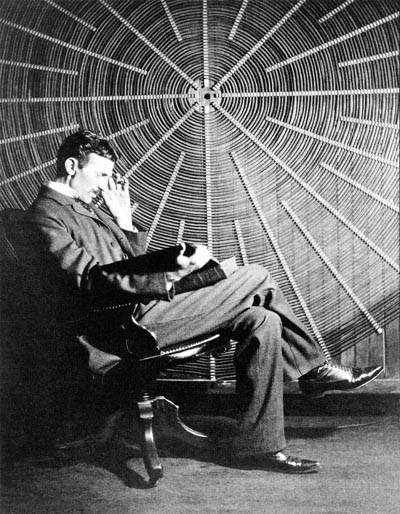

A hammer can be a tool or a weapon depending on how you swing it, but we can’t depend on implements or technology to bring about peace. In dedicating the opening of the Niagara Falls hydroelectric power plant on January 12, 1897, Nikola Tesla, who was born 156 years ago today, rightly announced the following century as one of science but didn’t foresee the horrors that such a shift would make possible. His speech:

“We have many a monument of past ages; we have the palaces and pyramids, the temples of the Greek and the cathedrals of Christendom. In them is exemplified the power of men, the greatness of nations, the love of art and religious devotion. But the monument at Niagara has something of its own, more in accord with our present thoughts and tendencies. It is a monument worthy of our scientific age, a true monument of enlightenment and of peace. It signifies the subjugation of natural forces to the service of man, the discontinuance of barbarous methods, the relieving of millions from want and suffering.”

Tags: Nikola Tesla

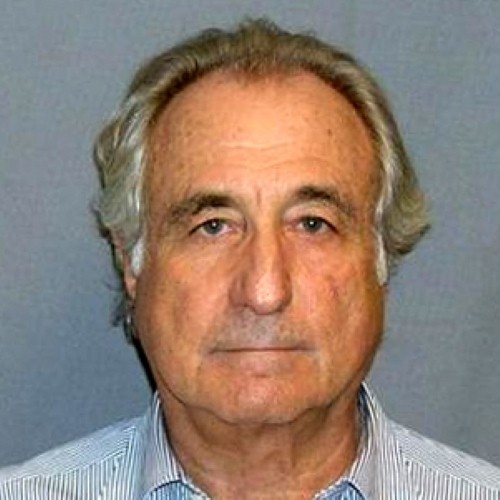

Sandy Hingston’s Philadelphia magazine article “The Psychopath Test” examines the work of Penn criminologist Adrian Raine, who believes that psychopathy may be largely a function of biology and that we may soon be able to detect such inclinations in small children. It’s hard to think of an ethically thornier topic. Raine explains how “successful psychopaths,” who share some traits with their murderous brethren, make their way in the world. An excerpt:

“Successful psychopaths, Raine’s research showed, have some of the negative brain-structure ‘hits’ of unsuccessful ones, but exhibit enhanced executive function. They don’t show significant gray matter reduction in the prefrontal cortex. Raine thinks the better frontal-lobe functioning makes them smarter, and more sensitive to environmental cues that predict danger and capture.

It may also make them ideal capitalists. The incidence of psychopathy in the business world is four times that of the general population. Psychopaths are reckless; when placing bets, they wager more the more they lose. The behavioral brakes the rest of us have are missing. ‘Individuals with psychopathic traits,’ Raine’s study of successful psychopaths states, ‘enter the mainstream workforce and enjoy profitable careers … by lying, manipulating and discrediting their co-workers.’ Closing factories and eliminating thousands of jobs requires a certain lack of empathy. So does generating sub-zero mortgages, or suggesting that a wife falsely accuse her husband of child abuse in a custody trial.

Raine isn’t arguing that any one brain malformation or genetic abnormality guarantees psychopathy—but he believes science will eventually pin down what does. What his studies show now is predisposition—the inclination toward evil. It can be reinforced by having bad parents or eating a bad diet; it can be mitigated by a positive environment and good food (but not always—plenty of psychos grow up in normal, loving homes). There are reasons for his caution. ‘We have a history of misusing research in society,’ he says, mentioning the Tuskegee Experiment.”

Tags: Sandy Hingston

From a discussion at the Browser with language scholar Nicholas Ostler, a passage about what technology and geopolitics might mean to the dominion of English and the dying of languages:

“Ostler: As things stand at the moment, the forces that have put English where it is – which mostly had to do with global economic power, first of the British Empire and then the United States – have come to the point where they are being overtaken. The crucial thing is that what put English where it is today is not going to be a feature in the future, and one has to think how the world is going to react to that. There will be other dominant powers which have non-English languages associated with them, notably the so-called BRIC countries – Brazil, Russia, India and China.

At the same time, we have a crisis in all the ‘little guys’ in the world’s languages, where we seem to be losing them at a very fast rate – something like two a month. There are a lot of languages around, perhaps 6,000 or 7,000, but if we continue to lose two a month we are going to see about half the world’s languages disappear in the course of a century. There is time for things to change. One of the things which is changing is the way we are using our languages and, in particular, their involvement with technology. One of the more significant developments in technology at the moment is machine translation and other electronic means of getting access to what’s going on in languages other than your own. These technologies are going to become more significant and are already becoming available to people who own handheld devices. If you combine that technical fact with the undying human preference for using one’s own language, you are going to see people using this technology to avoid having to resort to foreign languages such as English.”

Tags: Nicholas Ostler

From a well-written Financial Times piece by Simon Kuper about the rise (perhaps) of the technocrat and the privatazing of progress, although I think there is a middle ground between the Pol Pot’s perverted utopianism and Bill Clinton’s tireless triangulation:

“Politicians now try to present themselves not as saviours but as managers: Romney, Mario Monti and even Hollande. That’s no wonder, as since 1945 the managerialism of Dwight Eisenhower or Bill Clinton has fared rather better than the utopianism of, say, Pol Pot. As George Orwell wrote in 1943: ‘Plans for human betterment do normally come unstuck, and the pessimist has many more opportunities of saying ‘I told you so’ than the optimist.’ In Ukraine last month, a liberal dissident mused to me about who might be the country’s ideal leader, everyone else having failed. He came up with Lee Kuan Yew or General Franco. Progress has vanished not just from politics but from public life generally: the British municipal libraries that once stood for progress are now being closed.

However, progress has merely gone private. The western middle-classes increasingly believe in progress in their own lives. They read self-help books, take cooking classes, go on diets, stop smoking, do ‘home improvement,’ and have invented a new mode of parenting, ‘concerted cultivation,’ which largely means the sort of nonstop education for your own children that those moustachioed socialists had envisioned for the workers.”

Tags: Simon Kuper

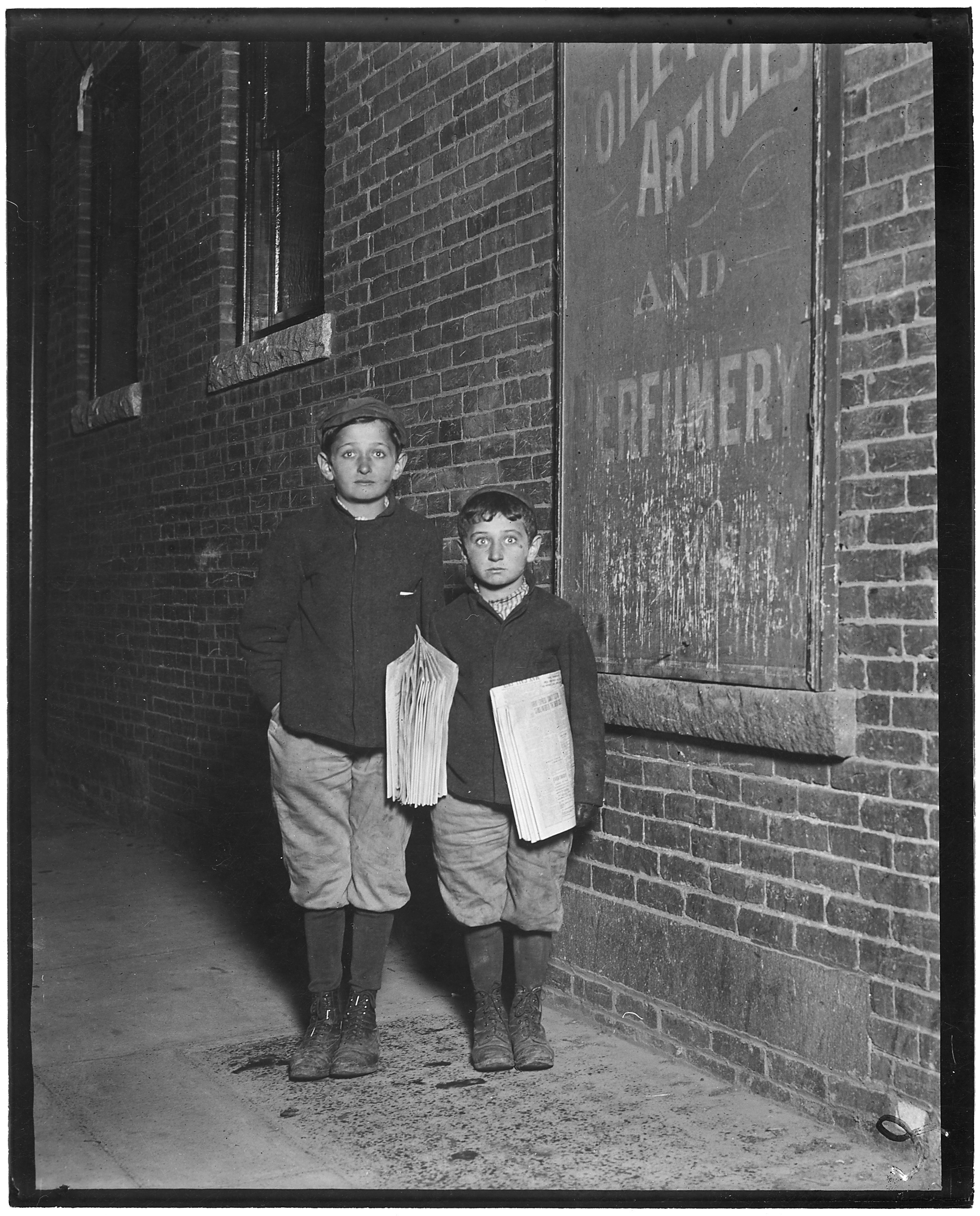

The New York Times’ David Carr, one of the nation’s very best newspaper writers, has a devastating article about the hopeless condition of newsprint in the Digital Age. It sounds more like a death knell than a clarion call. Of course, I read it online and even though I’m a complete news junkie I haven’t bought a paper in years. An excerpt:

“‘Most newspapers are in a place right now that they are going to have to make big cuts somewhere, and big seams are bound to show up at some point,’ said Rick Edmonds, a media business analyst at the Poynter Institute.

Some of the bigger cracks can’t be papered over by financial engineering. Hedge funds, which thought they had bought in at the bottom, are scrambling for exits that don’t exist. Many newspaper companies are hugely overburdened with debt from ill-timed purchases. And though it is far less discussed, newspapers are being clobbered by paltry returns on underfunded pension plans.

Two highly placed newspaper executives told me last week that while the industry had already experienced a number of strategic bankruptcies, more will most likely take place to deal with pension obligations.

As Mike Simonton of Fitch Ratings pointed out to me, very few bond investors are even willing to lend to papers. He said the pension obligations ‘represent a call on capital at a time when newspapers desperately need to deploy capital toward evolving their business models and adapting to the digital world.'”

Tags: David Carr

From Silicon Republic: “A group of researchers from University of Arizona in the US have come up with a robotic set of legs to mimic the act of walking. They’re claiming their robotic innovation is the first to fully model walking in a biologically accurate manner.

Researchers from the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at University of Arizona are behind the robotic legs. To create the legs, they studied the neural musculoskeletal architecture and sensory feedback pathways in humans, before simplifying them and weaving them into the robot to make it mirror the act of walking.”

From Sarah Korones Smart Planet piece about the cultural conditions that lead to creation:

“So which cultures lend themselves to innovation?

According to research from the Georgia Institute of Technology, both individualistic and patriotic cultures tend to breed innovation. After examining 20 years worth of data on 62 different countries, researchers found that individualism consistently had a strong, positive effect on innovation. But individual-centered cultures weren’t the only ones to breed success: certain types of collectivist cultures, like those with strong attitudes of patriotism and nationalism, also fared well on the advancement scale.

In cultures that place a premium on individuality, such as the U.S., the drive to innovate is closely linked to the personal rewards that might be reaped following the success of a new product or invention. One look towards Silicon Valley with its seemingly constant stream of millionaires and it’s not hard to see why so many people strive to create something new in America.

But some types of collectivist cultures enjoy equally high rates of innovation for completely different reasons.”

Tags: Sarah Korones

Every now and then, the perfect writer meets the perfect subject. Such is the case with Franklin Foer’s article of a doomed May-December D.C. relationship in this week’s New York Times Magazine. An excerpt from “The Worst Marriage in Georgetown,” a love story, among other things:

“From their first date, Viola and Albrecht enjoyed provoking one another. At night, they would lie in their separate beds, arguing in German. But every so often, their disagreements would escalate. In 1992, Muth was convicted of beating Drath, the beginning of a rap sheet that hardly reflects the many lesser occasions of abuse. Once when they were staying at the Plaza Hotel, he threw her clothes into the hall and locked her out of the room. ‘He has all my credit cards,’ she told Gary Ulmen on the phone, who rushed to the hotel and lent her cash to buy a train ticket back to Washington.

Where Drath nursed deep feelings and wrote passionately about her love for him, Muth was in the relationship for something else. He described their marriage as transactional, an example of a Washington coupling where husband and wife merge in order to aggregate their talents and social capital. When a local television reporter named Kris Van Cleave asked Muth how his marriage overcame so many obstacles, Muth replied, ‘Why does Secretary Clinton remain with President Clinton?’

Perhaps Drath should have suspected that he was gay earlier — he was actively having affairs with men. But once she came to terms with Muth’s sexual orientation, he did little to disguise it. He even briefly moved in with a boyfriend in 2002. ‘He was the boy, she was the wife,’ Muth explained in an e-mail he sent to friends. ‘You have the one for one set of reasons, the other another, the lives were fully integrated.’ They were so integrated that the boyfriend suffered the same abuse as the wife. When Muth threatened to kill him, he obtained a restraining order.

In May 2006, Drath was eating dinner on her couch while Muth sat on the other side of the room, drunk. Your daughter isn’t a lawyer, he blared to his wife, she’s a saleswoman. (In fact, she is a judge in Los Angeles.) It might have been best to let Muth rant, but Drath defended her daughter, telling Muth that he wasn’t smart enough to get into law school. According to the detectives’ report, he responded by swinging a chair at her, knocking her from the sofa and then repeatedly pounding her head against the floor. The next morning, Drath escaped to her daughter’s home and phoned 911. When the police finally arrested Muth, he left Drath behind — an exit everyone close to her hoped would be final.”

Tags: Albrecht Muth, Franklin Foer, Viola Drath

Biotech and performance enhancement will continue blurring more and more lines–and not just for horses. From Will Oremus at Slate:

‘Reversing an earlier ban, the international governing body for equestrian sports has decided that cloned horses can compete alongside their traditionally bred counterparts.

‘The FEI will not forbid participation of clones or their progenies in FEI competitions,’ the Federation Equestre Internationale said after its June meeting in Lausanne, Switzerland, according to The Chronicle of the Horse. ‘The FEI will continue to monitor further research, especially with regard to equine welfare.’

That’s good news for two companies—ViaGen in Texas and Cryozootech in France—that have successfully cloned champion horses, mainly for breeding purposes. Cryozootech has produced two clones of the American show-jumping champion Gem Twist. ViaGen, which owns the rights to the technology that produced the famous cloned sheep Dolly, has cloned several horses, including a quarter horse, a barrel racer, and a polo pony.”

••••••••••

Mark Walton, President of ViaGen, the “cloning company”:

Tags: Will Oremus

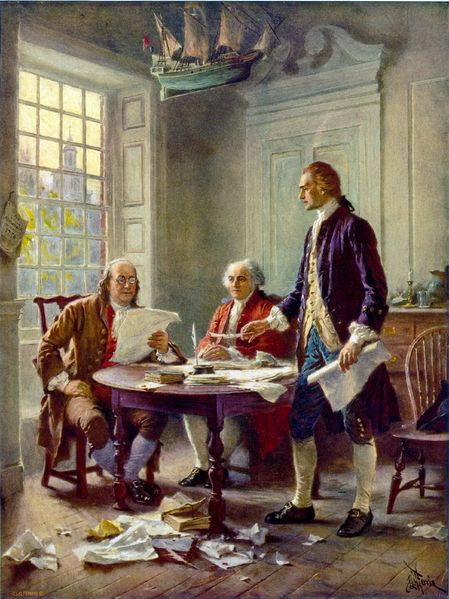

This week I’m going to read Thomas Fleming’s essay-length Kindle book, What America Was Really Like in 1776. The excerpt in the Wall Street Journal is well-written and informative, though it’s odd to comment on the U.S. economy of 236 years ago without mentioning slave labor. I’m sure the book goes into that topic, but the WSJ passage doesn’t. An excerpt:

“Those Americans, it turns out, had the highest per capita income in the civilized world of their time. They also paid the lowest taxes—and they were determined to keep it that way.

In the northern colonies, according to historical research, the top 10% of the population owned about 45% of the wealth. In some parts of the South, 10% owned 75% of the wealth. But unlike most other countries, America in 1776 had a thriving middle class. Well-to-do farmers shipped tons of corn and wheat and rice to the West Indies and Europe, using the profits to send their children to private schools and buy their wives expensive gowns and carriages. Artisans—tailors, carpenters and other skilled workmen—also prospered, as did shop owners who dealt in a variety of goods. Benjamin Franklin credited his shrewd wife, Deborah, with laying the foundation of their wealth with her tradeswoman’s skills.”

Tags: Thomas Fleming

Plenty of insiders were wrong about the Supreme Court decision regarding the Affordable Care Act, but how did large collections of outsiders do? Not so hot. From David Leonhardt’s analysis at the New York Times of the cooling of prediction markets and what that means:

“With the rumors swirling, I began to check the odds at Intrade, the online prediction market where people can bet on real-world events, several times a day. The odds had barely budged. They continued to show about a 75 percent chance that the law’s so-called mandate would be ruled unconstitutional, right up until the morning it was ruled constitutional.

The market — the wisdom of crowds — turned out to be wrong.

I have since come to think of the court’s ruling as the signature example of the counterattack of the insiders. After the better part of a decade in which various markets, from Intrade to the stock market, became many people’s preferred way to peer into the future, a backlash is clearly under way. Not so long ago, knowing about the existence of Intrade was a mark of being in the vanguard. Today, mocking Intrade, ideally on Twitter, is a sign of sophistication.

This development matters because predictions matter. They allow government officials, corporate executives and citizens to plan for the future. They are an unavoidable part of life.”

Tags: David Leonhardt

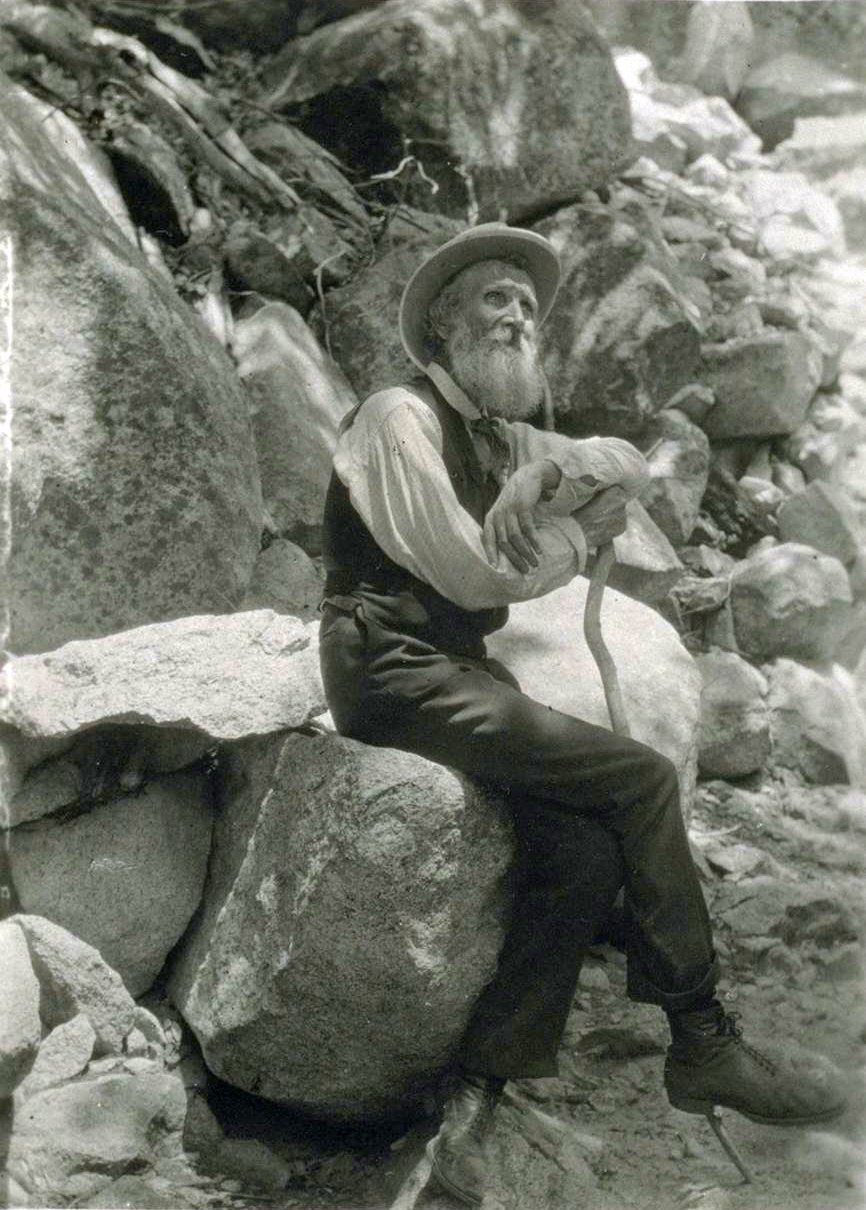

This classic photograph by Francis M. Fritz of John Muir shows the California conservationist in late life, seven years before his passing. Muir spent the majority of his years studying rocks, icebergs, forest and birds, and pressing successfully for the formation of national parks. A folksy story about him that was republished in the April 24, 1901 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

“A writer in Ainslie’s Magazine tells this of John Muir:

John Muir, the mountain climber, is a fascinating companion. He abounds in fun and his talk is apt to become a monologue, as listeners grow too interested even for comment. He runs in a steady, sparkling stream of witty chat, charming reminiscences of famous men, of bears in the woods and red men in the mountains; of walks with Emerson, of tossing in a frail kayak on the storm-tossed waters of Alaskan floods. By turn he is a scientist, mountaineer, story-teller and light-hearted school boy.

Alhambra Valley, where he has a home of many broad acres, is a beautiful vale curled down in the lap of Contra Costa hills, sheltered from every wind that blows and warmed to the heart by the genial California sunlight. Here he dwells, a slender, grizzled man, worn-looking and appearing older than he is, for hard years among the mountains have told upon him.

It was a fair picture of peace and plenty under the soft, blue September sky. A stream ran close at hand, shaded by alders and sycamores and the sweet-scented wild willow. On the bank nearest us stood a solitary blue crane, surveying us fearlessly. A flock of quail made themselves heard in the undergrowth, and low above the vineyards a shrike flew, uttering his sharp cry. Noting him I said to Mr. Muir:

‘So you don’t kill even the butcher birds?’

He looked up, following the bird’s flight.

‘Why, no,’ he said, ‘they are not my birds.'”

Tags: John Muir

Wall Street Journal reporter Scott Patterson, who covers the intersection of technology and finance, just conducted an Ask Me Anything on Reddit about his new book, Dark Pools: High-Speed Traders, A.I. Bandits, and the Threat to the Global Financial System. A few excerpts follow.

Question (nyseed): When you interviewed Mark Cuban about the problems with high-frequency trading you asked him “What’s the solution?” How would you respond to the same question?

Answer (scott_patterson): The regulators need to get on top of what’s going on and fast. The public is losing trust in the markets and right now our regulators can’t give them any assurances that they’re wrong. Right now we just don’t know and our regulators don’t either — that’s why the market is dark.

Question (davidmanheim): Is there a possibility of knowing what is going on if the markets remain fully automated, and computerized trading can go on at speeds that make the data processing to understand them so difficult? How can regulators understand a market with arbitrarily complex, constantly changing automatic program running on them? Do changes need to be made first?

Answer (scott_patterson): They simply need to get the computer fire power to monitor the market, and it exists. They just haven’t done it yet. There’s a proposal to build a so-called Conoslidated Audit Trail that could help solve some of these problems. I wrote about it for WSJ last year.

Question (hatetosayit): I’m suspicious about this concept have having a government computer monitor an automated market. As long as it’s a bunch of computers operating based on set rules, won’t there be room to invent new exploits that take advantage of those rules without being detected?

Answer (scott_patterson): Are you suspicious of cops using radar to catch speeders on the highway? Because right now the SEC doesn’t have that radar.

Question (nyseed): Honestly, how confident are you that this could actually happen? Can the public help? Or is reform just a faint hope?

Answer (scott_patterson): I’m not confident, but I’m hopeful. I’m hopeful that my book might help trigger enough outrage that they’re forced to do it. But it’s a hard fight because the industry has all the money and the lobbyists. Regulation is a dirty word on Wall Street.

Tags: Scott Patterson

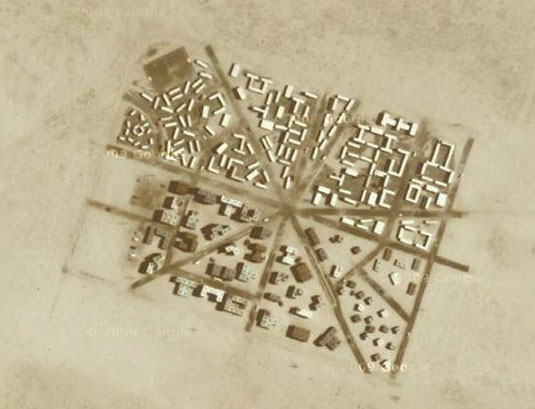

From BLDG BLOG, a post about Yodaville, an insta-ghost town in the Arizona desert that the U.S. military built to blow up:

“Yodaville is a fake city in the Arizona desert used for bombing runs by the U.S. Air Force. Writing for Air & Space Magazine back in 2009, Ed Darack wrote that, while tagging along on a training mission, he noticed ‘a small town in the distance—which, as we got closer, proved to have some pretty big buildings, some of them four stories high.’

As towns go, this one is relatively new, having sprung up in 1999. But nobody lives there. And the buildings are all made of stacked shipping containers. Formally known as Urban Target Complex (R-2301-West), the Marines know it as ‘Yodaville’ (named after the call sign of Major Floyd Usry, who first envisioned the complex).

As one instructor tells Darack, ‘The urban layout is actually very similar to the terrain in many villages in Iraq and Afghanistan.’

The Urban Target Complex, or UTC, was soon ‘lit up with red tracer rounds and bright yellow and white rocket streaks,’ till it “looked like it was barely able to keep standing.'”

From “Six Ways the Internet Will Save Civilization,” a really good 2010 Wired UK article by neuroscientist David Eagleman that has pretty much already proved to be true:

“Human capital is vastly increased

Crowdsourcing brings people together to solve problems. Yet far fewer than one per cent of the world’s population is involved. We need expand human capital. Most of the world does not have access to the education afforded a small minority. For every Albert Einstein, Yo-Yo Ma or Barack Obama who has educational opportunities, uncountable others do not. This squandering of talent translates into reduced economic output and a smaller pool of problem solvers. The net opens the gates education to anyone with a computer. A motivated teen anywhere on the planet can walk through the world’s knowledge — from the webs of Wikipedia to the curriculum of MIT’s OpenCourseWare. The new human capital will serve us well when we confront existential threats we’ve never imagined before.”

Tags: David Eagleman

When a pigeon in a lab setting believes wrongly that some incidental behavior it has displayed is the reason why it’s being fed, it takes about 1,000 repetitions in which the food no longer appears before the behavior ceases. Humans are also not always great at recognizing truth in patterns. Not every cluster has a cause. Spikes and discrepancies can occur naturally. They will occur naturally. It’s easy to confuse correlation and causation, to misread outliers. From B.F. Skinner’s 1948 paper “Superstition in the Pigeon“:

“The experiment might be said to demonstrate a sort of superstition.The bird behaves as if there were a causal relation between its behavior and the presentation of food, although such a relation is lacking. There are many analogies in human behavior. Rituals for changing one’s luck at cards are good examples. A few accidental connections between a ritual and favorable consequences suffice to setup and maintain the behavior in spite of many unreinforced instances.The bowler who has released a ball down the alley but continues to behave as if he were controlling it by twisting and turning his arm and shoulder is another case in point. These behaviors have, of course, noreal effect upon one’s luck or upon a ball half way down an alley, just as in the present case the food would appear as often if the pigeon did nothing — or, more strictly speaking, did something else.”

Tags: B.F. Skinner

From “Google Glass and the Rise of Outsourcing Our Memories,” Tom Chatfield’s new BBC piece about the future of brain augmentation in the face of seemingly infinite information:

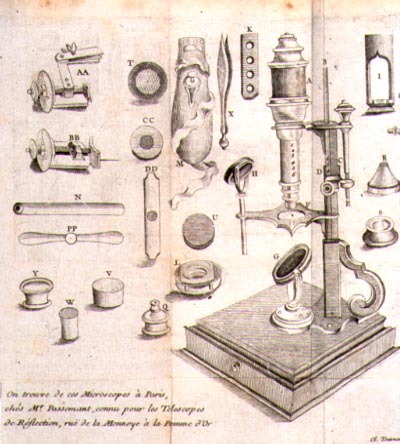

“As early as 1945, the American engineer and inventor Vannevar Bush described the potentials of a hypothetical system he dubbed ‘Memex’: a single device within which a compressed, searchable form of all the records and communications in someone’s life could be stored. It’s a project whose spirit lives on in Microsoft’s MylifeBits project, among other places, which attempted digitally to record every single aspect of a modern life – and presented the results in a book by researchers Gordon Bell and Jim Gemmell entitled Total Recall: How the E-Memory Revolution Will Change Everything.

What Google’s glasses suggest to me, though, is a giant leap forward in the sheer ease of capturing and broadcasting our lives from minute to minute – something that smartphones have already revolutionised once during the space of the last decade. Far more than mere technological possibility, it’s this portability and seamlessness that seem likely to most transform the way we live over the coming century. And it makes me wonder: what exactly does it mean when a computer’s memory becomes a more and more integral part of our own process of remembering?

The word ‘memory’ is the same in both cases, but there’s a huge gulf between the phenomena it describes in people and in machines. Computers’ memories offer a complete, faithful and objective record of whatever is put into them. They do not degrade over time or introduce errors. They can be shared and copied almost endlessly without loss, or precisely erased if preferred. They can be fully indexed and rapidly searched. They can be remotely accessed and beamed across the world in fractions of a second, and their contents remixed, augmented or updated endlessly.”

••••••••••

Animated version of Vannevar Bush’s Memex diagrams:

From “As We May Think,” by Vannevar Bush in the Atlantic,1945: “There is a growing mountain of research. But there is increased evidence that we are being bogged down today as specialization extends. The investigator is staggered by the findings and conclusions of thousands of other workers—conclusions which he cannot find time to grasp, much less to remember, as they appear. Yet specialization becomes increasingly necessary for progress, and the effort to bridge between disciplines is correspondingly superficial.

Professionally our methods of transmitting and reviewing the results of research are generations old and by now are totally inadequate for their purpose. If the aggregate time spent in writing scholarly works and in reading them could be evaluated, the ratio between these amounts of time might well be startling. Those who conscientiously attempt to keep abreast of current thought, even in restricted fields, by close and continuous reading might well shy away from an examination calculated to show how much of the previous month’s efforts could be produced on call. Mendel’s concept of the laws of genetics was lost to the world for a generation because his publication did not reach the few who were capable of grasping and extending it; and this sort of catastrophe is undoubtedly being repeated all about us, as truly significant attainments become lost in the mass of the inconsequential.

The difficulty seems to be, not so much that we publish unduly in view of the extent and variety of present day interests, but rather that publication has been extended far beyond our present ability to make real use of the record. The summation of human experience is being expanded at a prodigious rate, and the means we use for threading through the consequent maze to the momentarily important item is the same as was used in the days of square-rigged ships.

But there are signs of a change as new and powerful instrumentalities come into use.”

Tags: Gordon Bell, Jim Gemmel, Tom Chatfield, Vannevar Bush

If we’re wise, we play the odds, we take notice, we reduce risk. But some things are beyond our control, at birth and throughout our lives. Some of us get wicker furniture and some bubonic plague. From Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle:

“‘One time,’ said Castle, ‘when I was about fifteen, there was a mutiny near here on a Greek ship bound from Hong Kong to Havana with a load of wicker furniture. The mutineers got control of the ship, didn’t know how to run her, and smashed her up on the rocks near ‘Papa’ Monzano’s castle. Everybody drowned but the rats. The rats and the wicker furniture came ashore.’

That seemed to be the end of the story, but I couldn’t be sure. ‘So?’

‘So some people got free furniture, and some people got bubonic plague. At Father’s hospital, we had fourteen-hundred deaths inside of ten days. Have you ever seen anyone die of bubonic plague?’

‘That unhappiness has not been mine.’

‘The lymph glands in the groin and the armpits swell to the size of grapefruit.’

‘I can well believe it.’

‘After death, the body turns black–coals to Newcastle in the case of San Lorenzo. When the plague was having everything its own way, the House of Hope and Mercy in the Jungle looked like Auschwitz or Buchenwald. We had stacks of dead so deep and wide that a bulldozer actually stalled trying to shove them toward a common grave. Father worked without sleep for days, worked not only without sleep but without saving many lives, either.'”

Tags: Kurt Vonnegut

From “I Like to Build Alien Artifacts,” a Stephen Wolfram interview that ran in the European earlier this year, a segment about the possibilities of molecular-level computing:

“The European: I want to go back to the idea of the Turing machine. One of your arguments is that very simple programs can produce very complicated results – programs so simple that they could be encoded in a cell’s genome, for example.

Wolfram: Our intuition tends to be that we have to go through a lot of effort to build something that is complicated. But nature is very complex without going through a lot of effort: Evolution seems very complicated on a large time-scale, but the actual processes are not. They simply work and unfold and lead to new species. That was always a mystery to me, so a few years ago I began to experiment to see whether simple programs could produce very complex patterns of behavior. The question is: Is that how nature does it? I got a lot of evidence that in many cases, that is how nature works.

The European: This seems to contradict the general trend to drive technological innovation by packing more computational power into a single computer chip.

Wolfram: A couple of points. There is a phenomenon which I call computational irreducibility. When you have a process where the behavior is quite simple – like a planet orbiting around a star – we are smart enough to use math to figure out what will happen in the future without having to wait for the planet to move around. We can compute the outcome by plugging the right numbers into a formula. But many systems are irreducible after a number of steps – you really have to simulate each step to see what will happen. We need a lot of computational effort for that. But it’s a fallacy to believe that our current technology is the only possible computational technology. The fact is, we can make computers from a lot of materials, not just transistors. The reason that’s exciting is because it opens up the possibility of making a computer out of molecules. It hasn’t been done yet, and there’s a lot of ambient technology that is required to make a molecular computer possible. But it reminds us that we must not shrink transistors – we can use much simpler components.”

Tags: Stephen Wolfram

From “Hotel Offers Guests Electronic Bibles,” by Oliver Smith in the Telegraph:

“From today, all 148 rooms at the Hotel Indigo will contain a Kindle e-reader pre-loaded with a copy of the Bible. The hotel is claiming to be the first in Britain to offer such a service.

Guests are also permitted to download a copy of any other religious text – to the value of £5 or less – during their stay. Regular fiction books can also be purchased, with the costs added to guests’ bills.”

••••••••••

“That’s why the bible is the best seller in the world,” 1968:

Tags: Oliver Smith

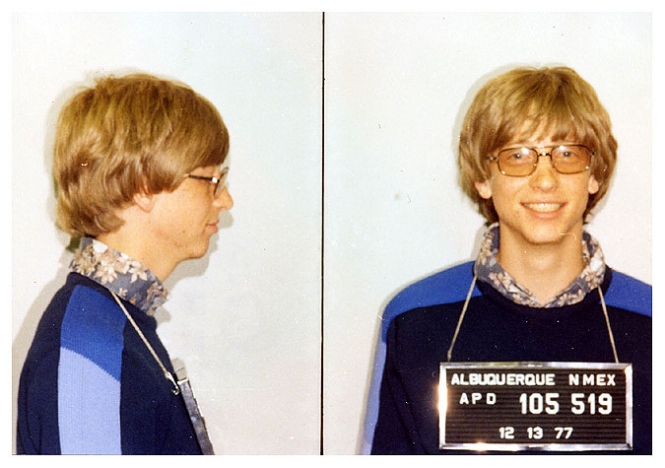

The toughest thing for a company to do is to become successful. The second toughest thing is to survive success and continue innovating. From a new Vanity Fair piece about the decline of Microsoft:

“According to [Kurt] Eichenwald, Microsoft had a prototype e-reader ready to go in 1998, but when the technology group presented it to Bill Gates he promptly gave it a thumbs-down, saying it wasn’t right for Microsoft. ‘He didn’t like the user interface, because it didn’t look like Windows,’ a programmer involved in the project recalls.

‘The group working on the initiative was removed from a reporting line to Gates and folded into the major-product group dedicated to software for Office,’ Eichenwald reports. ‘Immediately, the technology unit was reclassified from one charged with dreaming up and producing new ideas to one required to report profits and losses right away.’

‘Our entire plan had to be moved forward three to four years from 2003–04, and we had to ship a product in 1999,’ says Steve Stone, a founder of the technology group. ‘We couldn’t be focused anymore on developing technology that was effective for consumers. Instead, all of a sudden we had to look at this and say, ‘How are we going to use this to make money?’’

A former official in Microsoft’s Office division tells Eichenwald that the death of the e-reader effort was not simply the consequence of a desire for immediate profits. The real problem for his colleagues was the touch screen: “Office is designed to inputting with a keyboard, not a stylus or a finger,’ the official says. ‘There were all kinds of personal prejudices at work.’ According to Microsoft executives, the company’s loyalty to Windows and Office repeatedly kept them from jumping on emerging technologies. ‘Windows was the god—everything had to work with Windows,’ Stone tells Eichenwald. ‘Ideas about mobile computing with a user experience that was cleaner than with a P.C. were deemed unimportant by a few powerful people in that division, and they managed to kill the effort.'”

Tags: Bill Gates, Kurt Eichenwald, Steve Stone

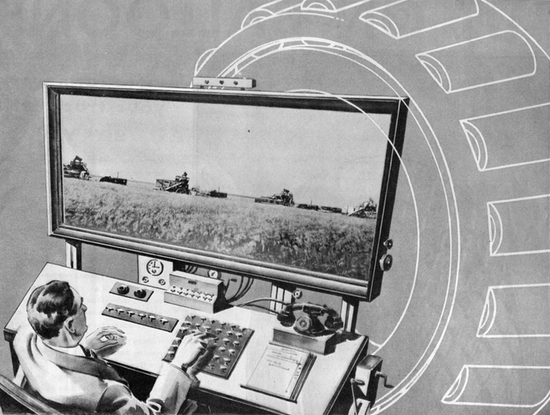

An excellent paleofuture find by Smithsonian Magazine is this 1931 advertisement from an agricultural periodical that imagined a high-tech future for farming. The opening:

“The March 1931 issue of The Country Gentleman magazine included this advertisement for Timken bearings. With the bold headline ‘100 YEARS AHEAD’ the ad promises that the farmer of the future may be unrecognizable — thanks to Timken bearings, of course. Our farmer of tomorrow wears a suit to work and sits at a desk that looks oddly familiar to those of us here in the year 2012. We’ve looked at many different visions of early television, but this flat panel widescreen display really stands out as exceptionally visionary. Rather than toil in the field himself, the farmer of the future uses television (something more akin to CCTV than broadcast TV) and remote controls to direct his farm equipment.”