From novelist Chloe Aridjis’ Granta article about cosmonauts trying to adjust to space–and readjust to Earth:

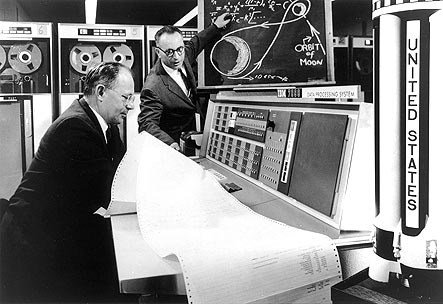

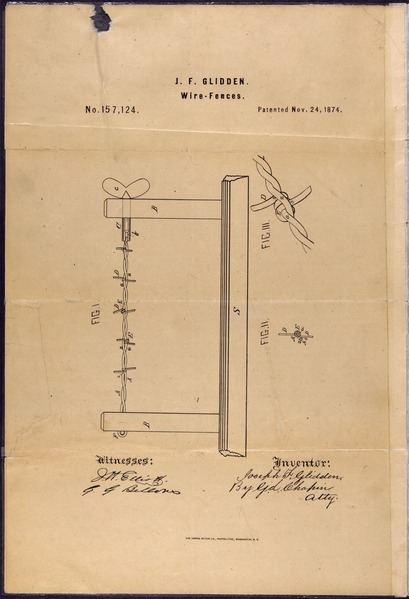

“Initially, it was unclear how man in space would react, how he would endure weightlessness and ‘unknown nervous-emotional overloads’. In a pre-emptive move, a ‘logic lock’ was installed aboard the Vostoks – early Soviet spacecrafts – to prevent any ‘irrational intervention of the cosmonaut in the direction of the ship’. Gagarin, for instance, had no control over his voyage.

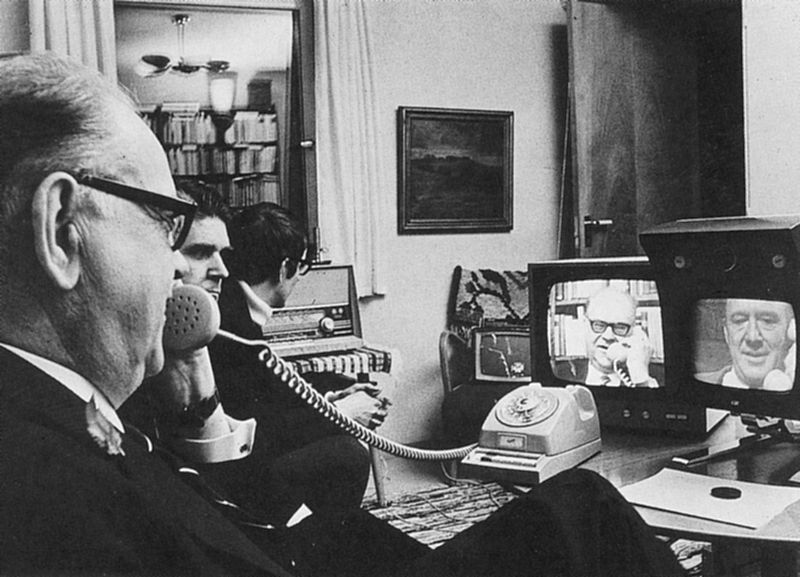

After all, in this world man and machine were one, incorporated into a single control system, its two main exponents poised to operate at highest potential and coherence. Yet despite all the preparation there were human variables, and the symbiotic relationship led to both real and imaginary ailments. One healthy cosmonaut, for instance, experienced cardiac arrhythmia after being exposed to sustained stressors related to onboard equipment failure.

During the first ninety-six-day Salyut mission in 1978, cosmonaut Yury Romanenko was apparently so mesmerized by the vastness of the cosmos that he stepped out to have a better look and forgot to attach himself with safety tethers to the space station. Fortunately his cohort noticed and quickly grabbed his foot as it floated out of the hatch. Even the most trained and disciplined individual could ignore all precautions and checklists and succumb to a greater urge.

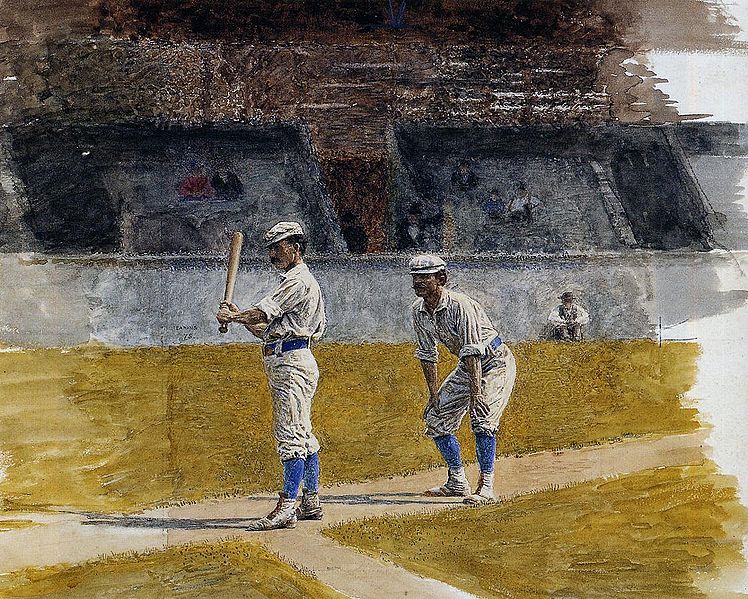

And then there was the monotony of space, the long stretches of nothingness, whether experienced alone – certainly the deepest emptiness of all – or in a small group, when tensions nearly always arose. Despite the speed of the aircraft, inside there was often no sensation of movement and everything appeared fixed and motionless. Moments of sensory bombardment alternated with extended periods of sensory deprivation. The first few cosmonauts were given books; later ones, curiously, were instead handed knives, wood blocks, coloured pencils and paper with which to pass the time. Some individuals would apparently become so exasperated with the lack of stimuli that they’d wish for the equipment to break down simply to provide some variety.”

••••••••••

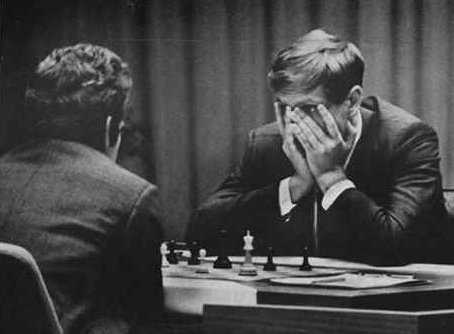

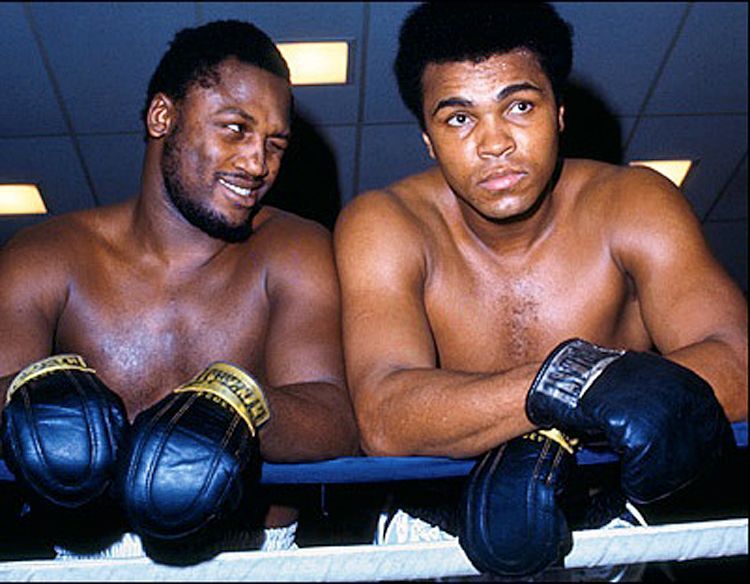

“I can assure you that I had no butterflies or anything else in my stomach”: