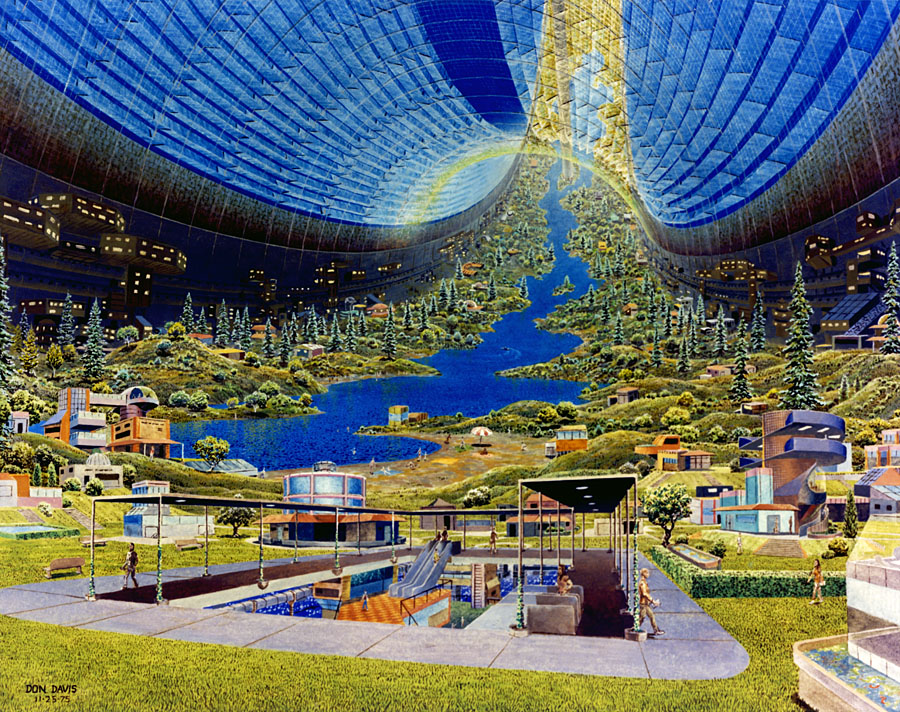

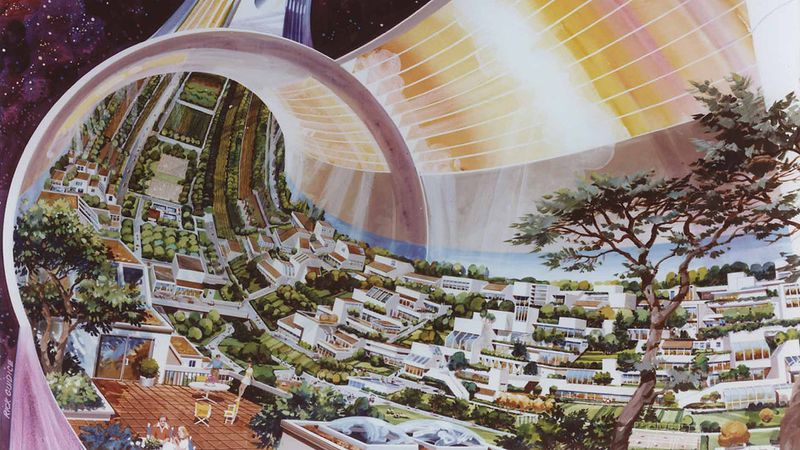

Scientist and space enthusiast Al Globus wrote the intro for the book Orbital Space Colonies, which was never published. Stratospheric cities, designed by NASA in the ’70s, have likewise not come to fruition. From Globus’ intro:

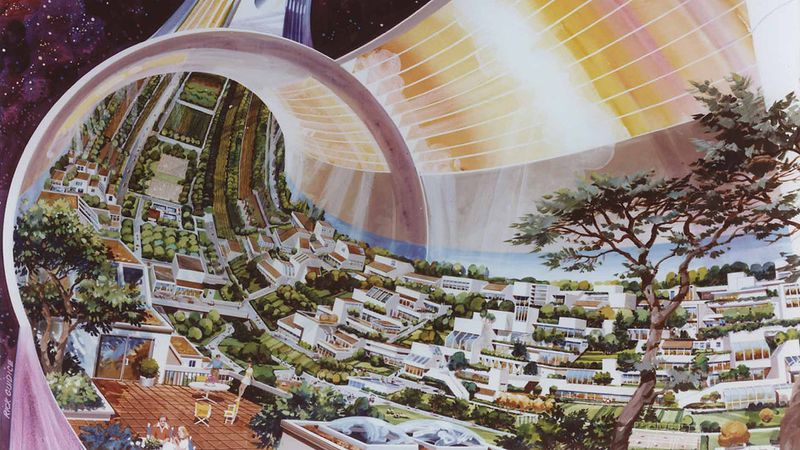

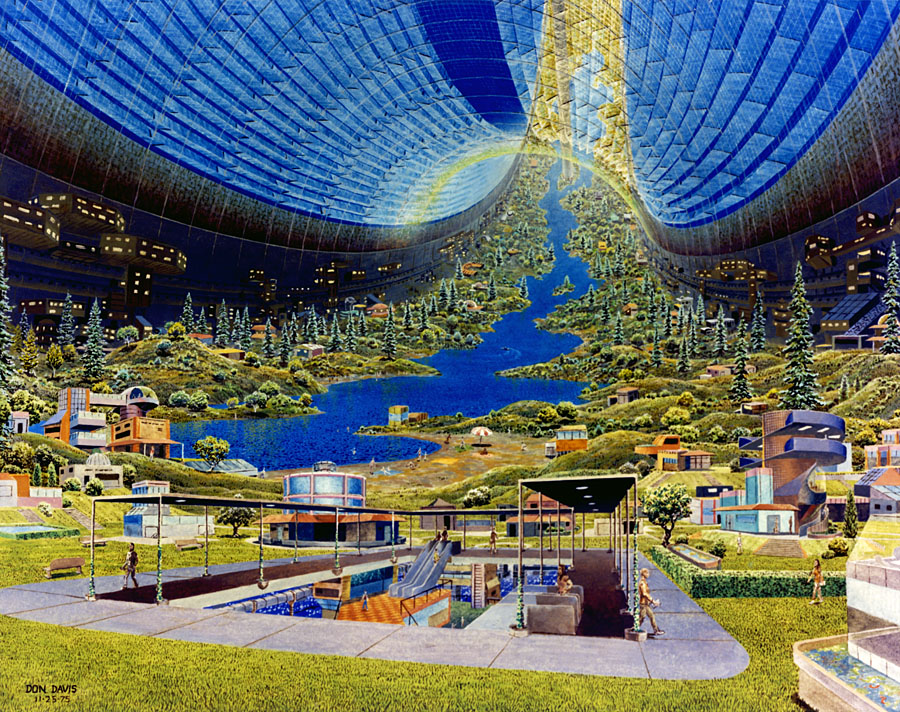

“Humanity has the power to fill outer space with life. Today our solar system is filled with plasma, gas, dust, rock, and radiation — but very little life; just a thin film around the third rock from the Sun. It’s time to change that. In the 1970’s Princeton physicist Gerard O’Neill with the help of NASA Ames Research Center and Stanford University showed that we can build giant orbiting spaceships and live in them. These orbital space colonies can be wonderful places to live; about the size of a California beach town and endowed with weightless recreation, fantastic views, freedom, elbow-room in spades, great wealth and true independence.

We can be life’s taxi to the stars — or at least to the rest of this solar system. Given the will, mankind can build first-class orbital real estate sufficient for perhaps a trillion people to live in luxury. If this sounds ridiculous, consider your great-great grandfather’s reaction if you told him that by the year 2000, hundreds of millions of people would fly each year.

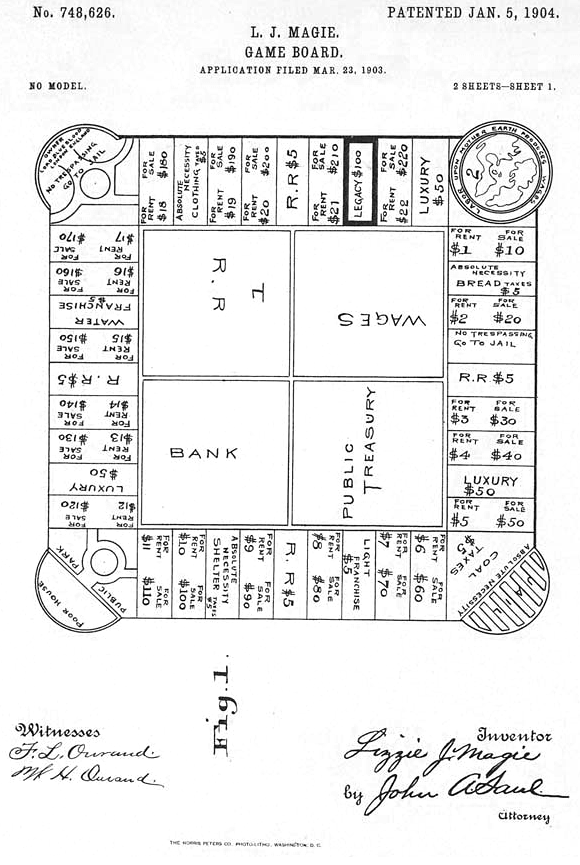

When the first American landed on the moon in 1969 after only eight short years of intense effort, the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) proved that we could do nearly anything consistent with the laws of physics. A few years later, Princeton physicist Gerard O’Neill and others showed that orbital space colonies were physically possible (Johnson and Holbrow, 1975) (O’Neill, 1977). Dr. O’Neill’s analysis strongly suggested that asteroids and lunar mines could supply the materials, the Sun could provide the energy, and that our technology had nearly reached the point where we could build orbital cities. These cities could be placed anywhere in the solar system, although beyond Mars nuclear power might need to replace solar energy. O’Neill speculated that we would be well on the way to building orbital colonies by now. We aren’t.

There were two flaws in Dr. O’Neill’s vision, both of which can be fixed. First, transportation is vital and he assumed that NASA’s space shuttle would function as advertised, including a planned fifty flights per year at a cost of $500 per pound to orbit; this turned out to be false. Second, even with the promised transportation system, Dr. O’Neill knew that building the first colony would involve a titanic up-front financial investment. This investment would take decades to generate any return, much less a profit. Orbital Space Colonies follows in Dr. O’Neill’s footsteps with improvements; showing how to develop the necessary transportation and colonize the solar system with merely an extremely large investment; but one that produces some returns fairly quickly. This book proposes a human space program driven by tourism, real estate, energy, and strategic materials; a program that will garner great power and wealth to those who pursue it.

To colonize the solar system, we need to adjust our thinking a bit. We are planetary surface creatures. That is where we live, where we’ve evolved, and we’re good at it. Living inside giant space ships is foreign to our thinking. But there is precious little usable planetary surface in our solar system, so it’s very valuable. Hundreds of billions of dollars and many lives are spent on sophisticated military ventures to take and hold territory. However, a small fraction of that money could build the first orbital colonies within a few decades. This would eventually provide access to hundreds of times the currently available useful land area and millions of times the energy we now control. Materials from the single largest known asteroid are sufficient to build orbital space colonies with living areas more than two hundred times the surface area of the Earth. These are facts that make one wonder why we work so hard for chump change like Mid-East oil and spend so little on space colonization.

The fact remains that orbital colonization will be expensive and most paths involve enormous up-front costs before any return on investment. The approach presented in this book is to pay as we go: take one step at a time, each as simple as possible, and each one more capable than the last. These steps are at least arguably, although perhap not actually, profitable and lead us to a time when we finally build a colony that is attractive to the average middle-class family. That first colony can then build more colonies. At that stage, we have a reproducing seed that, like life on Earth, can spread to fill all livable space. Since the livable space is anywhere in the vastness of the solar system, the limits to growth will be eliminated for quite some time.

Malthus, an influential Englishman, noticed that plants and animals produce far more offspring than can survive, and that people can do the same. Around 1800 he predicted that without family size controls mankind would increase in number until all available resources were exhausted; after famine and deadly epidemics would rule. Malthus and other limits to growth adherents were and are incorrect. They didn’t consider that, unlike animals and plants, mankind’s knowledge almost always increases, and that knowledge multiplies the available resources. In the last hundred years knowledge has accumulated at an astonishing and increasing pace. In particular, we now have much of the knowledge needed to open the door to the resources of this solar system. These resources might be exhausted one day, but it will take many thousands of years. That’s good enough for now.

The dinosaurs failed, after millions of successful years, because an asteroid struck the Earth and wiped them out. Since then we have become a space-faring species with the power to avoid that fate by building orbital space settlements housing perhaps a trillion people and a vast cornucopia of plants and animals. Expanding throughout the solar system can be our destiny.

The universe is waiting for us.”