The origin story of the board game Monopoly from a Christopher Ketcham article in Harper’s:

“The game’s true origins, however, go unmentioned in the official literature. Three decades before [Charles] Darrow’s patent, in 1903, a Maryland actress named Lizzie Magie created a proto-Monopoly as a tool for teaching the philosophy of Henry George, a nineteenth-century writer who had popularized the notion that no single person could claim to ‘own’ land. In his book Progress and Poverty (1879), George called private land ownership an ‘erroneous and destructive principle’ and argued that land should be held in common, with members of society acting collectively as ‘the general landlord.’

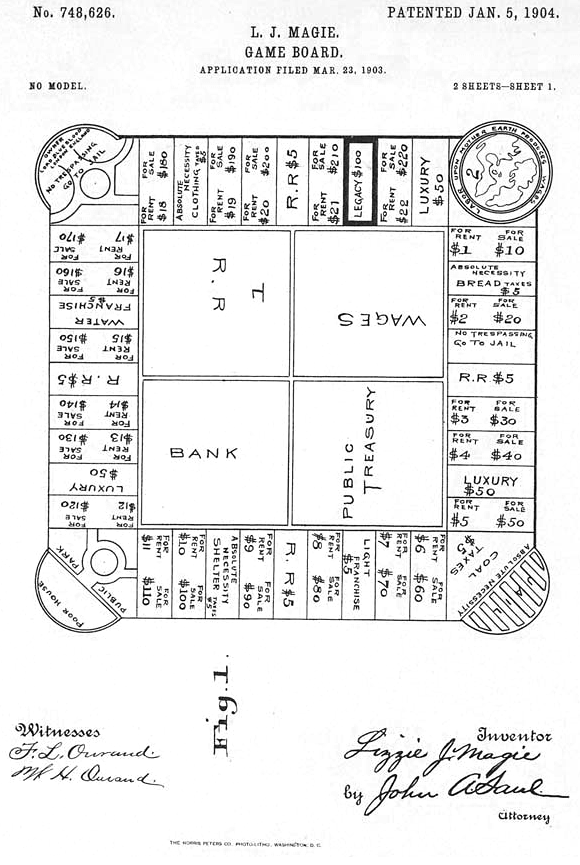

Magie called her invention The Landlord’s Game, and when it was released in 1906 it looked remarkably similar to what we know today as Monopoly. It featured a continuous track along each side of a square board; the track was divided into blocks, each marked with the name of a property, its purchase price, and its rental value. The game was played with dice and scrip cash, and players moved pawns around the track. It had railroads and public utilities—the Soakum Lighting System, the Slambang Trolley—and a ‘luxury tax’ of $75. It also had Chance cards with quotes attributed to Thomas Jefferson (‘The earth belongs in usufruct to the living’), John Ruskin (‘It begins to be asked on many sides how the possessors of the land became possessed of it’), and Andrew Carnegie (‘The greatest astonishment of my life was the discovery that the man who does the work is not the man who gets rich’). The game’s most expensive properties to buy, and those most remunerative to own, were New York City’s Broadway, Fifth Avenue, and Wall Street. In place of Monopoly’s ‘Go!’ was a box marked ‘Labor Upon Mother Earth Produces Wages.’ The Landlord Game’s chief entertainment was the same as in Monopoly: competitors were to be saddled with debt and ultimately reduced to financial ruin, and only one person, the supermonopolist, would stand tall in the end. The players could, however, vote to do something not officially allowed in Monopoly: cooperate. Under this alternative rule set, they would pay land rent not to a property’s title holder but into a common pot—the rent effectively socialized so that, as Magie later wrote, ‘Prosperity is achieved.’

For close to thirty years after Magie fashioned her first board on an old piece of pressed wood, The Landlord’s Game was played in various forms and under different names—’Monopoly,’ ‘Finance,’ ‘Auction.’ It was especially popular among Quaker communities in Atlantic City and Philadelphia, as well as among economics professors and university students who’d taken an interest in socialism. Shared freely as an invention in the public domain, as much a part of the cultural commons as chess or checkers, The Landlord’s Game was, in effect, the property of anyone who learned how to play it.” (Thanks Browser.)

Tags: Charles Darrow, Christopher Ketcham, Henry George, Lizzie Magie