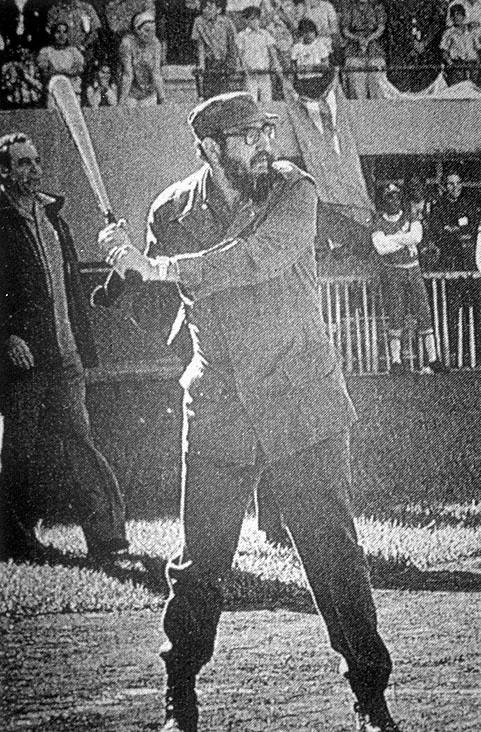

[A NECESSARY INTRODUCTION By FIDEL CASTRO]

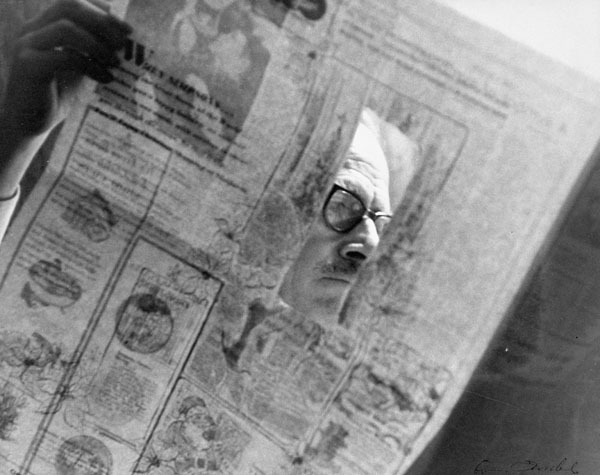

IT WAS CHE’S HABIT during his days as a guerrilla to write down his daily observations in a personal diary. During the long marches over abrupt and difficult terrain, in the middle of the damp woods, when the lines of men, always hunched over from the weight of their mochilas, munitions and arms would stop for a moment to rest, or when the column would receive orders to halt and pitch camp at the end of a long day’s journey, one could see Che—as he was from the beginning affectionately nicknamed by the Cubans—take out his notebook and, with the small and almost illegible letters of a doctor, write his notes. What he was able to conserve from these notes he later used in writing his magnificent historical narrations of the revolutionary war in Cuba. They were of revolutionary content, pedagogic and human.

This time, thanks to his invariable habit of jotting down the principal occurrences of each day, we have at our disposal rigorously exact, priceless and detailed information concerning the heroic final months of his life in Bolivia.

These notations, not exactly written for publication, served him as a working guide in the constant evaluation of the occurrences, the situation and the men. They also served as an expressive outlet for his profoundly observant spirit, analytical but often laced with a fine sense of humor. They are soberly written and contain an uninterrupted coherence from the beginning to the end.

It should be kept in mind that they were written during those rare moments of rest in the middle of an heroic and superhuman physical endeavor—notwithstanding Che’s exhausting obligations as chief of a guerrilla detachment in the difficult first stages of a struggle of this nature—which unfolded under incredibly hard material conditions, revealing once more his particular way of working and his will of steel. In the diary, detailed analyses of the incidents of each day, the faults, criticisms and recriminations which are appropriate to and inevitable in the development of a revolutionary guerrilla are made evident.

In the heart of a guerrilla detachment, these criticisms must take place incessantly, especially when there is only a small nucleus of men, constantly confronted by extremely adverse material conditions and an enemy infinitely superior in number, when a little carelessness or the most insignificant mistake can be fatal and the chief has to be extremely demanding. He must use each occurrence or episode, no matter how insignificant, as a lesson to the combatants and future leaders of new guerrilla detachments.

The formation of a guerrilla is a constant call to the conscience and honor of every man. Che knew how to touch on the most sensitive fibers of the revolutionaries. When Marcos, repeatedly admonished by Che, was warned that he could be dishonorably discharged from the guerrillas, he said, “First I must be shot!” Later on he gave his life heroically. The behavior of all the men in whom Che put his confidence and whom he had to admonish for some reason or another during the course of the struggle was similar. He was a fraternal and human chief who also knew how to be exacting and occasionally even severe, but above all, and even more so than with the others, Che was severe with himself. He based the discipline of the guerrilla on their moral conscience and on the tremendous force of his own personal example.

The diary also contains numerous references to Regis Debray and makes evident the enormous preoccupation stirred up in Che by the arrest and imprisonment of the revolutionary writer whom he had made responsible for carrying out a mission in Europe, although in reality he would have preferred Debray to remain in the guerrilla. This is why he manifests a certain inconsistency and occasionally some doubts concerning his behavior.

For Che it was not possible to know of the odyssey lived by Debray and the firm and courageous attitude he took in front of his capturers and torturers while he was in the clutches of the repressive forces.

However, he did emphasize the enormous political importance of Debray’s trial, and on the 3rd of October, six days before his death, in the midst of tense and bitter happenings, Che stated; “An interview with Debray was heard, very valiant when faced with a student provocator,” this being his last reference to the writer.

Since in this diary the Cuban Revolution and its relation to the guerrilla movement are repeatedly pointed out, some might interpret the fact that its publication on our part constitutes an act of provocation supplying an argument to the enemies of the Revolution—the Yankee imperialists and their cohorts, the Latin American oligarchies—for redoubling their plans for blockade, isolation of and aggression toward Cuba.

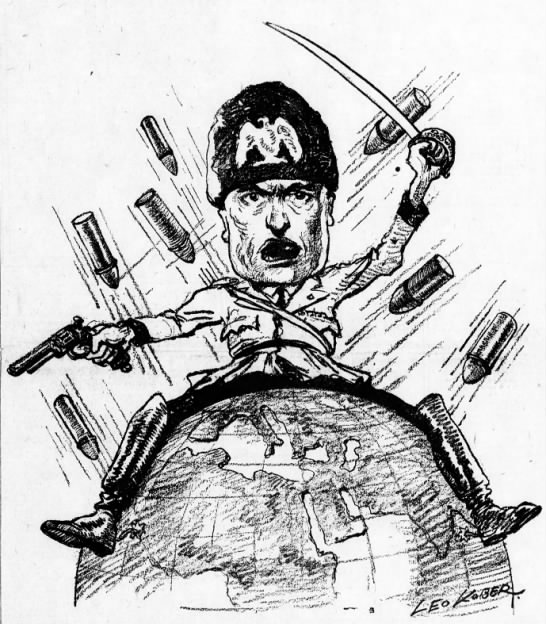

For those who judge the facts in this way it is well to remember that Yankee imperialism has never needed pretexts to perpetrate its villainy in any part of the world and that its efforts to smash the Cuban Revolution began with the first revolutionary law made in our country; for the obvious and well-known fact is that imperialism is the gendarme of the world, systematic promoter of counterrevolution and protector of the most backward and inhuman social structures in the world.

Solidarity with the revolutionary movement might be used as a pretext but shall never be the cause of Yankee aggression. Denying solidarity in order to deny the pretext is ridiculous ostrich-like politics, which has nothing to do with the internationalist character of contemporary social revolutions. To cease solidarity with the revolutionary movement does not mean to deny a pretext but actually to show solidarity with Yankee imperialism and its policy of domination and enslavement of the world.

CUBA IS A SMALL economically underdeveloped country, like all those countries dominated and exploited by colonialism and imperialism. It is situated only 90 miles from the United States’ coast, having a Yankee naval base on its own territory, and confronts numerous obstacles in the carrying out of its economic and social development. Great dangers have threatened our country since the triumph of the Revolution but not because of this will imperialism succeed in making us yield, since the difficulties which a consequent revolutionary line entails are not important to-us.

From the revolutionary point of view, the publication of Che’s diary in Bolivia admits no alternative. Che’s diary fell into Barrientos’ possession who immediately sent copies to the CIA, the Pentagon and the United States government. Newspapermen connected with the CIA had access to the document in Bolivia and have made photostatic copies of it—but with the promise to abstain from publishing it for

the moment. Barrientos’ government and his highest military chiefs have abundant reasons for not publishing the diary since it confirms the tremendous incapacity of the Bolivian Army and the innumerable defeats which it suffered at the hands of a small fistful of determined guerrillas who captured almost 200 arms in combat in a few weeks.

Che also describes Barrientos and his regime in terms which they deserve and with words that cannot be erased from history.

On the other hand, imperialism had its reasons: Che and his extraordinary example gain increasing force in the world. His ideas, his image, his name, are the banners of the struggle against the injustices of the oppressed and exploited and stir up a passionate interest on the part of students and intellectuals all over the world.

Right in the United States, members of the Negro movement and the radical students, who are constantly increasing in number, have made Che’s figure their own. In the most combative manifestations of civil rights and against the aggression in Vietnam, his photographs are wielded as emblems of the struggle. Few times in history, or perhaps never, has a figure, a name, an example, been so universalized with such celerity and passionate force. This is because Che embodies in its purest and most disinterested form the internationalist spirit which characterizes the world today and which will do so even more tomorrow.

From a continent oppressed by colonial powers yesterday and exploited and kept down in the most iniquitous underdevelopment by Yankee imperialism today, there surges breath of the revolutionary struggle, even in the imperialist and colonial metropolises themselves.

The Yankee imperialists fear the force of this example and all that may contribute to reveal it. The intrinsic value of the diary, the living expression of an extraordinary personality, is as a guerrilla lesson written in the heat and tension of each day. It is inflammable gun powder. It is the real demonstration that Latin American man is not impotent in the face of those who would enslave the peoples with their mercenary armies and who prevented the publication of this diary until now.

It could also be that the pseudorevolutionaries, opportunists and charlatans of every kind who call themselves Marxists, communists, or give themselves any other titles, are interested in keeping the diary from being known. They have not vacillated in qualifying Che as wrong, as an adventurer, and when referring to him in the most benign form, they call him an idealist whose death is the Swan Song of the revolutionary armed struggle in Latin America.

“If Che,” they exclaim, “the highest exponent of these ideas and an experimented guerrilla fighter, was killed in guerrilla warfare and his movement did not liberate Bolivia, this only demonstrates how wrong he was!” How many of these miserable characters have been happy about the death of Che and haven’t even blushed to think that their position and reasoning coincide completely with those of the most reactionary oligarchies and with imperialism!

In this way they justify themselves or justify treacherous leaders who at certain moments have not vacillated in playing a game of armed struggle with the real purpose of destroying the guerrilla detachments, as could be seen later, putting the brake on revolutionary action and asserting their shameful and ridiculous political deals because they were absolutely incapable of any other line; or they justify those who do not want to fight, who will never fight, for the peoples and their liberation and who have caricatured the revolutionary ideas turning them into a dogmatic opium without content or any message for the masses, converting the organizations of the people’s struggle into instruments of conciliation with external and internal exploiters and proponents of politics which have nothing to do with the real interest of exploited peoples on this continent Che contemplated his death as something natural and probable in the process and tried to emphasize, especially in

the last documents, that this eventuality would not impede the inevitable march of the revolution in Latin America.

In his message to the Tricontinental Congress, he reiterated this thought: “Our every action is a battle cry against imperialism. . . wherever death may surprise us, let it be welcome, provided that this, our battle cry, may have reached some receptive ear and another hand may be extended to wield our weapons.”

He considered himself a soldier of this revolution without ever worrying about surviving it. Those who see the end to his ideas in the outcome of his struggle in Bolivia could with the same simplicity negate the validity of the ideas and struggles of all the great precursors and revolutionary thinkers, including the founders of Marxism who were unable to culminate their work and see during their lifetimes the fruits of their noble efforts.•