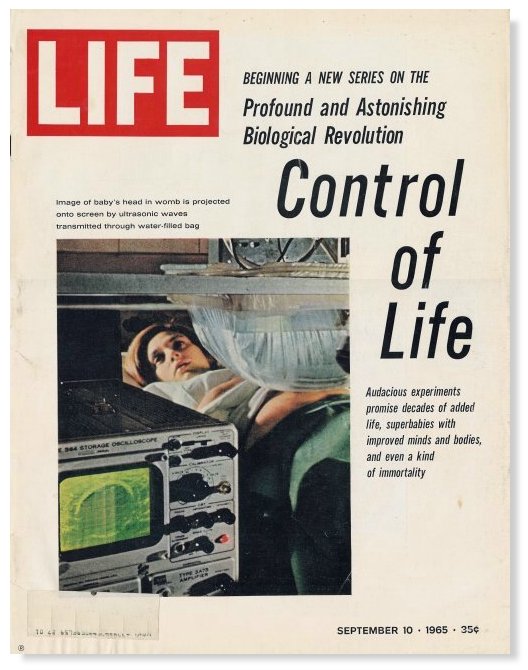

Here’s a question worth asking: Why do we get outraged over the unfairness of athletes using PEDs to become superior but have no problem with some competitors having ridiculous genetic advantages? We cheat and so does nature. It’s not something that exists only in racehorses but in people as well. Doesn’t this have something to do with the quaint notion of humans not upsetting God or else, I don’t know, lighting bolts will be thrown from the sky? The opening of “Man and Superman,” Malcolm Gladwell’s New Yorker piece which begins with an example from David Epstein’s book, The Sports Gene:

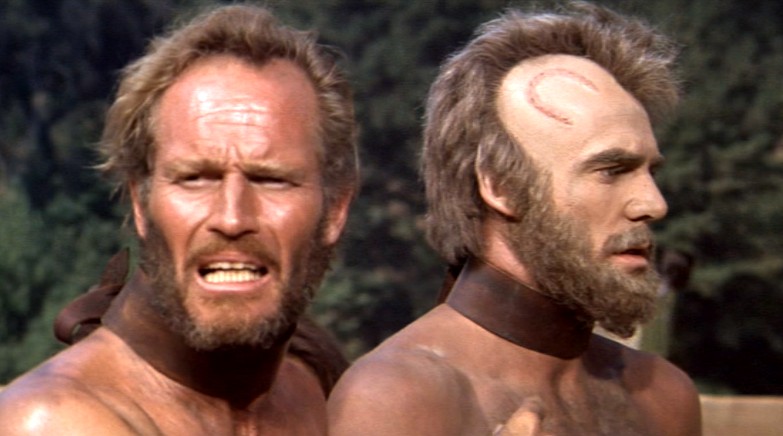

“Toward the end of The Sports Gene (Penguin/Current), David Epstein makes his way to a remote corner of Finland to visit a man named Eero Mäntyranta. Mäntyranta lives in a small house next to a lake, among the pine and spruce trees north of the Arctic Circle. He is in his seventies. There is a statue of him in the nearby village. ‘Everything about him has a certain width to it,’ Epstein writes. ‘The bulbous nose in the middle of a softly rounded face. His thick fingers, broad jaw, and a barrel chest covered by a red knit sweater with a stern-faced reindeer across the middle. He is a remarkable-looking man.’ What’s most remarkable is the color of his face. It is a ‘shade of cardinal, mottled in places with purple,’ and evocative of ‘the hue of the red paint that comes from this region’s iron-rich soil.’

Mäntyranta carries a rare genetic mutation. His DNA has an anomaly that causes his bone marrow to overproduce red blood cells. That accounts for the color of his skin, and also for his extraordinary career as a competitive cross-country skier. In cross-country skiing, athletes propel themselves over distances of ten and twenty miles—a physical challenge that places intense demands on the ability of their red blood cells to deliver oxygen to their muscles. Mäntyranta, by virtue of his unique physiology, had something like sixty-five per cent more red blood cells than the normal adult male. In the 1960, 1964, and 1968 Winter Olympic Games, he won a total of seven medals—three golds, two silvers, and two bronzes—and in the same period he also won two world-championship victories in the thirty-kilometre race. In the 1964 Olympics, he beat his closest competitor in the fifteen-kilometre race by forty seconds, a margin of victory, Epstein says, ‘never equaled in that event at the Olympics before or since.’

In The Sports Gene, there are countless tales like this, examples of all the ways that the greatest athletes are different from the rest of us. They respond more effectively to training. The shape of their bodies is optimized for certain kinds of athletic activities. They carry genes that put them far ahead of ordinary athletes.”