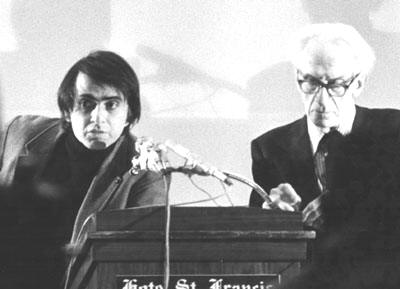

In 1988, as Gabriel Garcia Marquez was about to publish Love in the Time of Cholera, he sat for an interview with Marlise Simons of the New York Times. An excerpt:

Question:

You have said that your stories often come from a single image that strikes you.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez:

Yes. In fact, I’m so fascinated by how to detect the birth of a story that I have a workshop at the cinema foundation called ‘How to Tell a Story.’ I bring together 10 students from different Latin American countries and we sit at a round table without interruption for four hours a day for six weeks and try to write a story from scratch. We start by going round and round. At first there are only differences. . . . The Venezuelan wants one thing, the Argentine another. Then suddenly an idea appears that grabs everyone and the story can be developed. We’ve done three so far. But, you know, we still don’t know how the idea is born. It always catches us by surprise.

In my case, it always begins with an image, not an idea or a concept. With Love in the Time of Cholera, the image was of two old people dancing on the deck of a boat, dancing a bolero. Once you have the image, then what happens? The image grows in my head until the whole story takes shape as it might in real life. The problem is that life isn’t the same as literature, so then I have to ask myself the big question: How do I adapt this, what is the most appropriate structure for this book? I have always aspired to finding the perfect structure. One perfect structure in literature is that of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex. Another is a short story, ‘Monkey’s Paw’ by an English writer, William Jacobs.

When I have the story and the structure completely worked out, I can start – but only on condition that I find the right name for each character. If I don’t have the name that exactly suits the character, it doesn’t come alive. I don’t see it.

Once I sit down to write, usually I no longer have any hesitations. I may take a few notes, a word or a phrase or something to help me the following morning, but I never work with a lot of notes. That’s what I learned when I was young. I know writers who have books full of notes and they wind up thinking about their notes and never write their books.

Question:

You’ve always said you still feel as much a journalist as a writer of fiction. Some writers think that in journalism the pleasure of discovery comes in the research, while in fiction the pleasure of discovery comes in the writing. Would you agree?

Gabriel Garcia Marquez:

Certainly there are pleasures in both. To begin with, I consider journalism to be a literary genre. Intellectuals would not agree, but I believe it is. Without being fiction, it is a form, an instrument, for expressing reality.

The timing may be different but the experience is the same in literature and journalism. In fiction, if you feel you get a scoop, a scoop about life that fits into your writing, it’s the same emotion as a journalist when he gets to the heart of a story. Those moments occur when you least expect them and they bring extraordinary happiness. Just as a journalist knows when he’s got the story, a writer has a similar revelation. Of course, he still has to illustrate and enrich it, but he knows he’s got it. It’s almost an instinct. The journalist knows if he has news or not. The writer knows if it’s literature or not, if it’s poetry or not. After that, the writing is very much the same. Both use many of the same techniques. But your journalism is not exactly orthodox. Well, mine isn’t informative, so I can follow my own preferences and look for the same veins I look for in literature. But my misfortune is that people don’t believe my journalism. They think I make it all up. But I promise you, I invent nothing either in journalism or fiction. In fiction, you manipulate reality because that’s what fiction is for. In journalism, I can pick the subjects that suit my character because I no longer have the demands of a job.

Question:

Do you remember any of your journalistic pieces with special affection?

Gabriel Garcia Marquez:

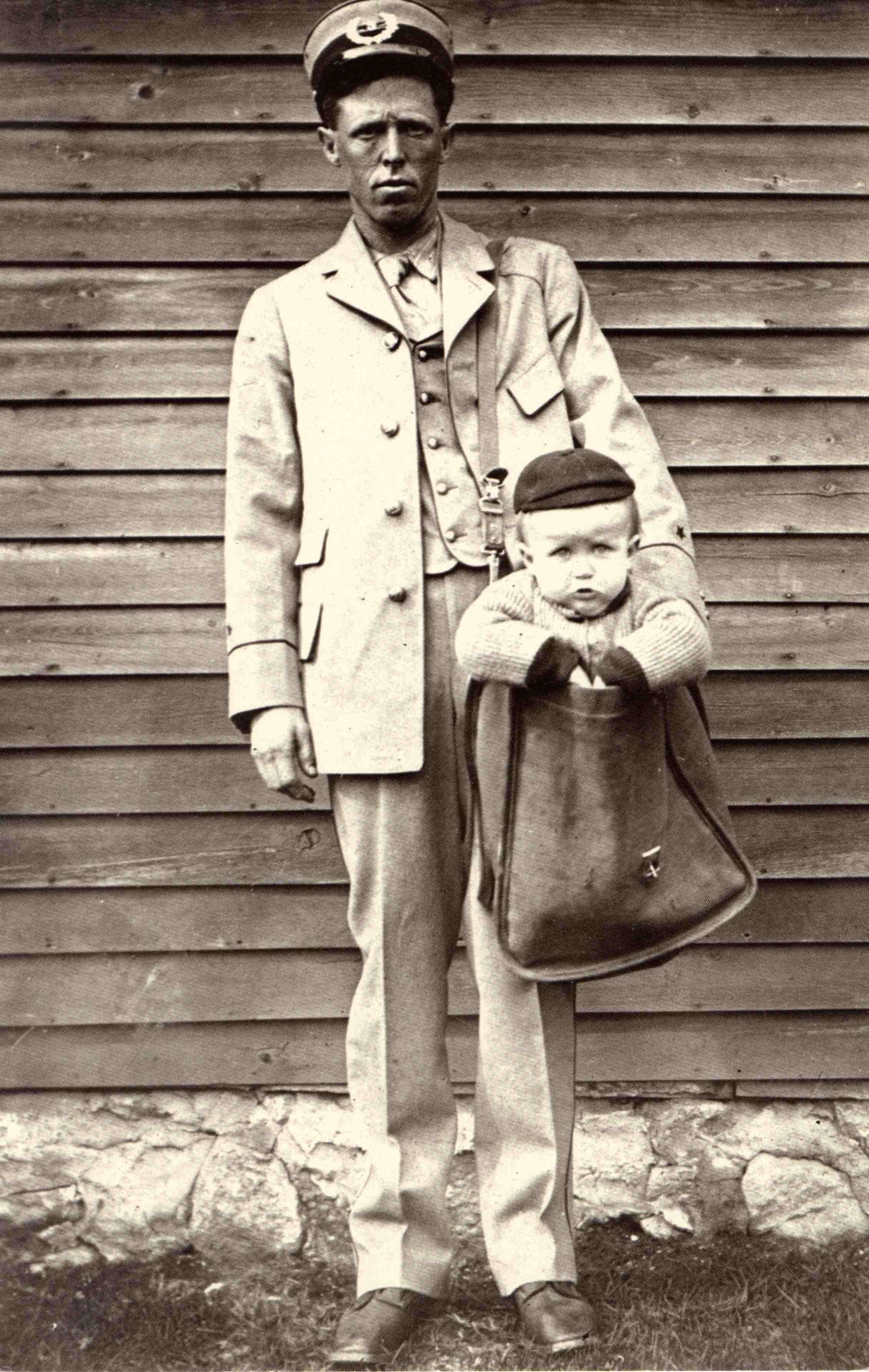

There was one little one called ‘The Cemetery of Lost Letters,’ from the time I was working at El Espectador. I was sitting on a tram in Bogota. And I saw a sign that said: ‘House of Lost Letters.’ I rang the bell. They told me that all the letters that could not be delivered – with wrong addresses, whatever – were sent to that house. There was an old man in it who dedicated his life entirely to finding their destination. Sometimes it took him days. If it couldn’t be found, the letter was burned but never opened. There was one addressed ‘To the woman who goes to the Church de Las Armas every Wednesday at 5 P.M.’ So the old man went there and found seven women and questioned each of them. When he had picked the right one, he needed a court order to open the letter to be sure. And he was right. I’ll never forget that story. Journalism and literature were almost joined. I have never been able to completely separate them.”