Some people who should know better are perplexingly treating that murderer Michael Alig like he’s a cute celebrity with some gossip to dish–you know, a reality star who just so happens to be clutching a bloody knife and a bottle of Drano–rather than a narcissistic murderer who dismembered another human being. These college-educated geniuses send out happy tweets about Alig’s post-prison menu and such. One meshuganah at the Huffington Post who interviewed the killer referred to him as a “rehabilitated citizen,” as if he would actually know. Emma Brockes of the Guardian is the latest to unfortunately interview Alig, but at least she gets to the heart of the new abnormal while analyzing a lowlife who thinks he’s something else. An excerpt:

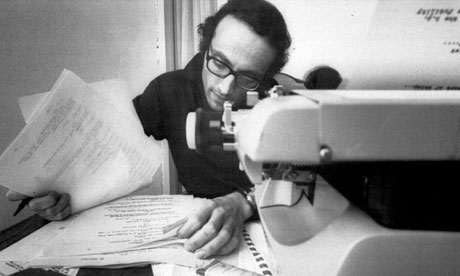

“For a year or so before he left prison, Michael Alig was phoning in tweets to a friend on the outside, who updated his account with aperçus from the exercise yard and cute observations about daytime TV. How did Justin Bieber get his hair to stand up like that? Why was everyone so mean to Madonna? After almost two decades inside, Alig’s persona seemed little changed from the 1990s, when his fame as the king of the New York club scene rested on a combination of low humour, high camp and the laboriously outrageous (one of his signature moves was to urinate in people’s drinks). ‘I just look ADORABLE in my mess-hall whites & hair-net,’ ran a typical tweet from earlier this year. ‘Where are the paparazzi when you need them?’

Since the 48-year-old’s release last month, it’s a tone that has jarred with expectations of what remorse looks like, and Alig has had to temper his adorableness with lots of qualifiers about how sorry he is, an effort undermined by those of his friends who turned up at the prison gates to greet him. As the media waited, and Alig emerged looking slight and sober, a group of ageing ex-club kids giddy on Red Bull and vodka bounced around laughing and screaming, as if serving 17 years for manslaughter were just another of Alig’s inventive, satirical breaks with convention. ‘I wouldn’t go so far as to say I’d have thrown them out,’ he says now, ‘but they probably weren’t people I would have invited.’ He does his best to look chastened.

No matter how disagreeable the crime or the perpetrator, a celebrity felon is protected from the full force of public condemnation by the buffer of his fame. Someone who has it all and squanders it should, if anything, incur less sympathy than a regular criminal, but they don’t. The height of the fall is so great, and the public humiliation so widespread, that any show of contrition is received as the satisfying end to a well-wrought story (I’m thinking primarily of Jonathan Aitken here).

And so it has been with Alig, whose US publicity blitz in the few weeks after his release has reasserted him as a celebrity first, convicted killer second.”