As I write this post, smart money would be on the American Health Care Act failing to win the necessary votes, oddly because it’s too draconian for some Republican lawmakers and not enough for others, with Trump and Congress then settling for doing all in their power to undermine Obamacare into collapse.

The latter has already begun in earnest with tweaks made to weaken the ACA and the pulling of advertising campaigns aimed at increasing enrollment. The GOP’s gambit is that citizens will blame the previous Administration as the healthcare law implodes, but it could ultimately be pinned on the actual culprits, costing them control of one or more branches of the government. The only sure thing is that citizens will be hurt.

In a Reddit Ask Me Anything, John McDonough, professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, answered questions about the AHCA, which even Trump doesn’t want to attach his for-sale surname to. A few exchanges follow.

Question:

If you had carte blanche to write health care policy for the US, what would be the key points?

John McDonough:

Honestly, even though I think it won’t happen anytime soon, a single payer type system with protections and guarantees makes the most sense. Shorter term — it’s nuts that we have 3 gigantic federal health programs: Medicare, Medicaid, and ACA. Makes sense to me to move toward a consolidated federal health system/approach.

Question:

If you were a benevolent dictator, what would you do to control health care costs?

John McDonough:

Here are some options: 1. A single payer is an effective way to control costs because the government sets a strict limit. It can also lead to significant limitations in funding the system adequately. EG: Canada has a great system, but it has been suffering considerably over recent years because of strict funding limits put in place back in the 1970s, and it is falling behind. 2. Government price regulation is another approach that is less strict than single payer, and also marginally less effective — though it provides space for more give and take between the system providers and the payers. 3. Leave it to the market — that’s been the main approach since the Reagan era in the 1980s (interrupted by Obama in the past 8 years) and it has led to the largest explosion of costs ever.

So I pick #2, though not bursting with enthusiasm.

Question:

Why is the U.S. so against a single payer system when it works in so many other developed nations?

John McDonough:

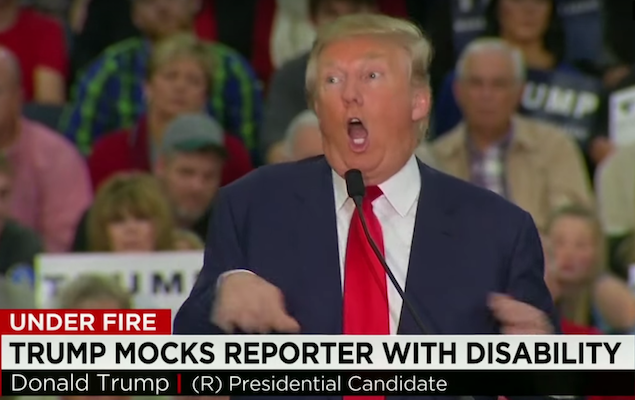

Lots of reasons. A few: 1. so much of what we pay for healthcare right now is hidden — in employer contributions, in tax deductions, in government payments, so very few see the real cost. When people see the real cost in a single payer plan, many get scared and freak out. 2. Conservatives really fear giving that much power to the federal government — it runs heavily against the deep seeded grain of libertarianism in our culture. 3. Path dependence — if we were starting from scratch (say when Harry Truman tried it in 1948), it was easier. Now there is so much that gets replaced and it gets so — as DT says — “complicated.” 4. Large wealthy interests will spend lots of $ to confuse people.

Question:

Do you think that Obamacare and the ACA were a good or bad foot forward to having more affordable Healthcare, and if so, why?

John McDonough:

I believe that the ACA, overall, was a strong net positive for the US, recognizing that many elements could be improved/strengthened.

-

More than 20 million formerly uninsured got coverage

-

Medicaid got improved enormously in helping people get on and stay on

-

Medicare costs, on a per enrollee basis, since the ACA and because of it, have risen since 2009 as the lowest rate of increase since the program was created in 1965

-

The US medical system, significantly because of the ACA, is embracing a new improvement agenda to fix costs, quality, and efficiency — and the health system is embracing that changeLots more — those are the biggies.

Question:

It appears right now that the AHCA is “DOA” in the Senate, in Ted Cruz’s words. What are the GOP’s next steps? A new, different, more conservative bill? One that uproots the structures created by the ACA? Accept the ACA and just fix some of the deficiencies? Throw in the towel?

John McDonough:

Here is my fear, not hypothetical, and repeatedly mentioned by Trump.

ACA needs work and repair — totally doable and 100% necessary. Can be done, but Rs don’t want it fixed, they want it dead.

So Rs refuse to do any repairs, and let it devolve into chaos and just say the law is fatally flawed and it’s the D’s fault.

Could happen, and hard to game out the result. That seems to me to be the most likely piece.

Remember, this is about tax policy as much as about health policy. The key reason Rs are so fixed on getting this done is the tax cuts/repeals which play a big part in the tax reform agenda they want to do right after this.•