The future usually arrives wearing the clothes of the past, but occasionally we truly and seriously experience the shock of the new. On that topic: The 1965 Life magazine piece “Will Man Direct His Own Evolution?” is a fun but extremely overwrought essay by Albert Rosenfeld about the nature of identity in a time when humans would be made by design, comprised of temporary parts. Like a lot of things written in the ’60s about science and society, it’s informed by an undercurrent of anxiety about the changes beginning to affect the nuclear family. An excerpt:

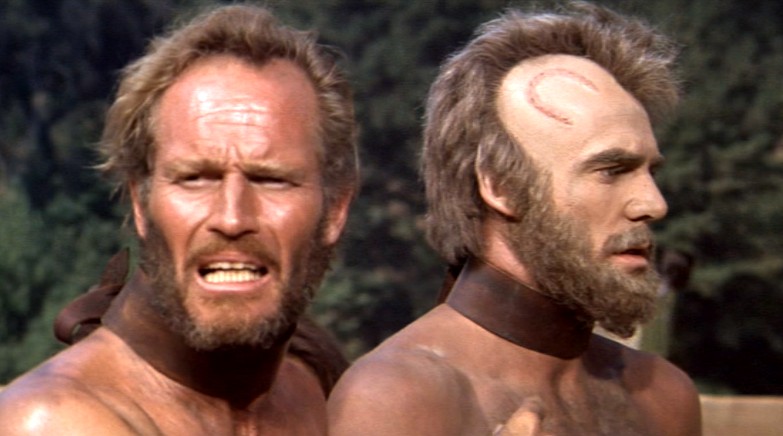

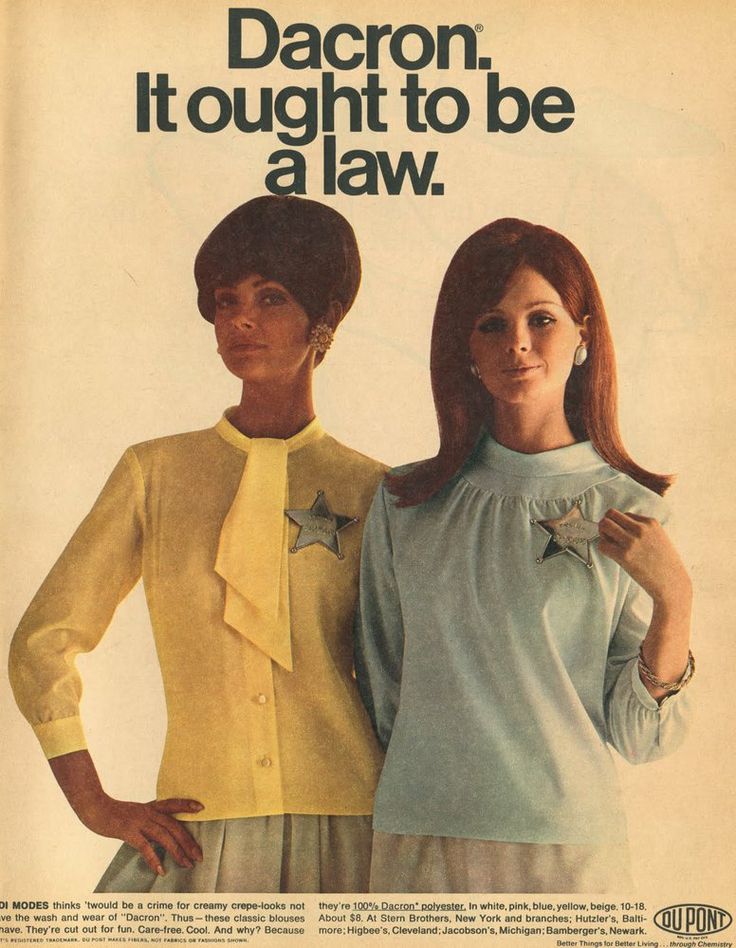

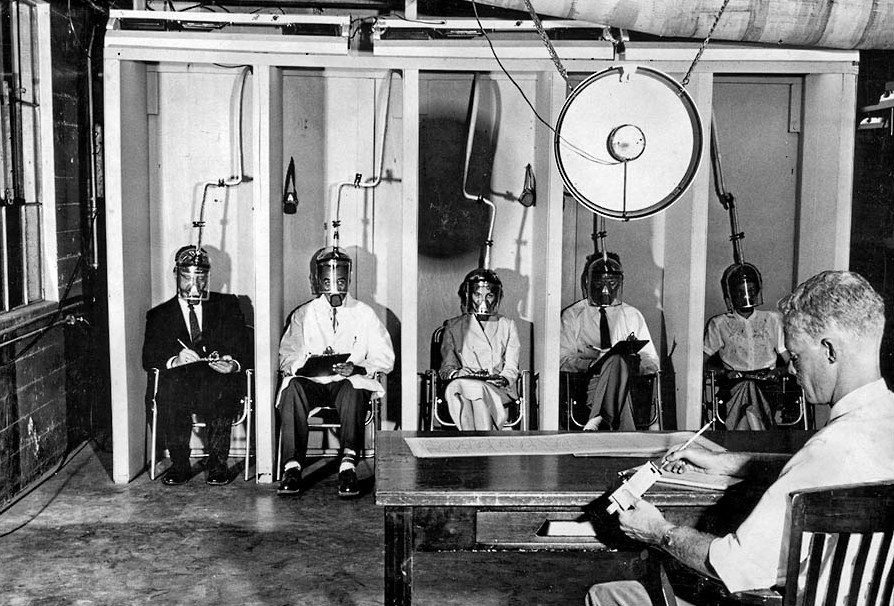

Even you and I–in 1965, already here and beyond the reach of potential modification–could live to face curious and unfamiliar problems in identity as a result of man’s increasing ability to control his own mortality after birth. As organ transplants and artificial body parts become even more available it is not totally absurd to envision any one of us walking around one day with, say, a plastic cornea, a few metal bones and Dacron arteries, with donated glands, kidney and liver from some other person, from an animal, from an organ bank, or even an assembly line, with an artificial heart, and computerized electronic devices to substitute for muscular, neural or metabolic functions that may have gone wrong. It has been suggested–though it will almost certainly not happen in our lifetime–that brains, too, might be replaceable, either by a brain transplanted from someone else, by a new one grown in tissue culture, or an electronic or mechanical one of some sort. ‘What,’ asks Dr. Lederberg, “is the moral, legal or psychiatric identity of an artificial chimera?”

Dr. Seymour Kety, an outstanding psychiatric authority now with the National Institute of Health, points out that fairly radical personality changes already have been wrought by existing techniques like brainwashing, electroshock therapy and prefrontal lobotomy, without raising serious questions of identity. But would it be the same if alien parts and substances were substituted for the person’s own, resulting in a new biochemistry and a new personality with new tastes, new talents, new political views–-perhaps even a different memory of different experiences? Might such a man’s wife decide she no longer recognized him as her husband and that he was, in fact, not? Or might he decide that his old home, job and family situation were not to his liking and feel free to chuck the whole setup that have been quite congenial to the old person?

Not that acute problems of identity need await the day when wholesale replacement of vital organs is a reality. Very small changes in the brain could result in astounding metamorphoses. Scientists who specialize in the electrical probing of the human brain have, in the past few years, been exploring a small segment of the brain’s limbic system called the amygdala–and discovering that it is the seat of many of our basic passions and drives, including the drives that lead to uncontrollable sexual extremes such as satyriasis and nymphomania.

Suppose, at a time that may be surprisingly near at hand, the police were to trap Mr. X, a vicious rapist whose crimes had terrorized the women of a neighborhood for months. Instead of packing him off to jail, they send him in for brain surgery. The surgeon delicately readjusts the distorted amygdala, and the patient turns into a gentle soul with a sweet, loving disposition. He is clearly a stranger to the man who was wheeled into the operating room. Is he the same man, really? Is he responsible for the crimes that he–or that other person–committed? Can he be punished? Should he go free?

As time goes on, it may be necessary to declare, without the occurrence of death, that Mr. X has ceased to exist and that Mr. Y has begun to be. This would be a metaphorical kind of death and rebirth, but quite real psychologically–and thus, perhaps, legally.•