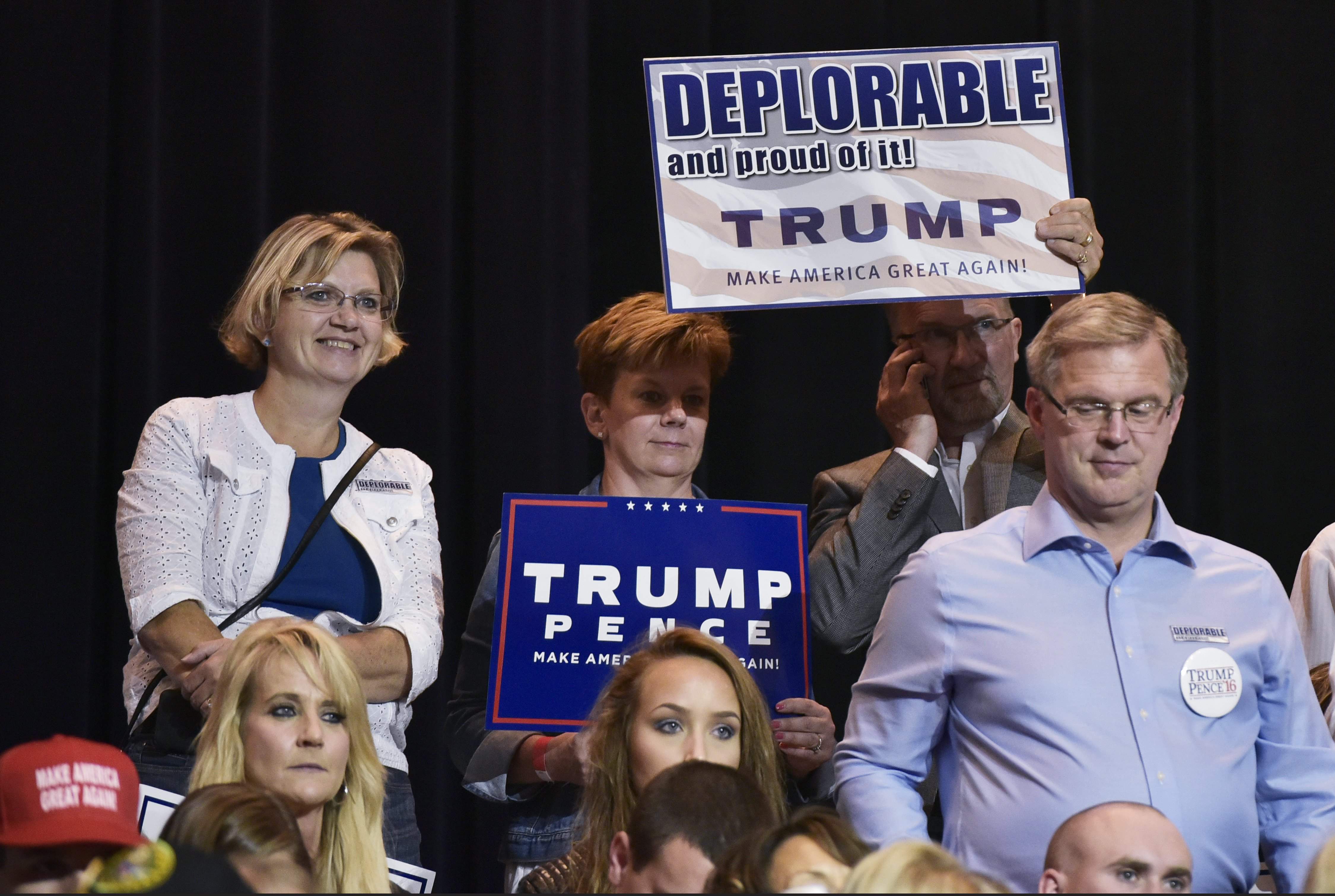

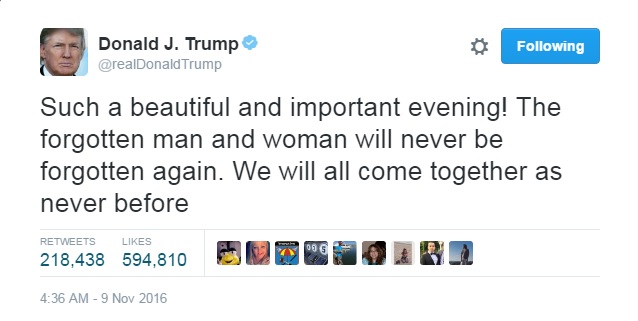

Bernie Sanders, whose TV campaign ads were even a shade more alabaster than Trump’s, is a politician, so he has to choose his words carefully when speaking to supporters of the Ku Klux Kardashian, reassuring them that they’re not deplorables, even if many are.

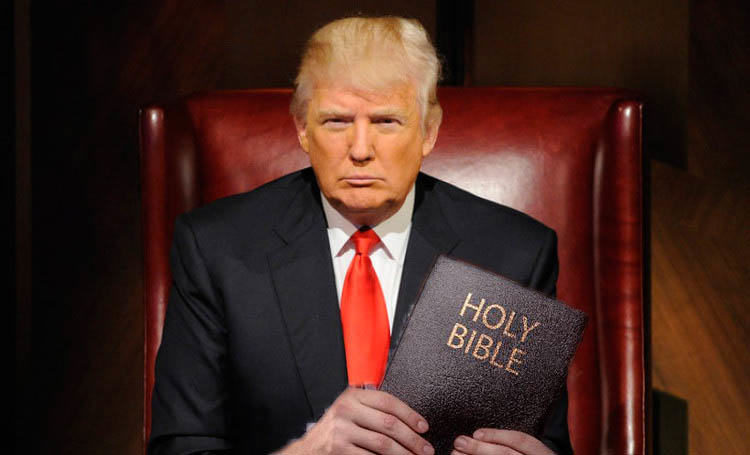

The coded racist language the GOP has employed over the last 50 years became explicit in the candidacy of Trump, who falsely blamed non-white “others” for the nation’s ills, promising to corral them, and to pull away benefits from “those people” living off the system. The not-so-subtle joke was that the conman was talking about taking his crude scissors to a social safety net that was helping to hold aloft many of his very voters.

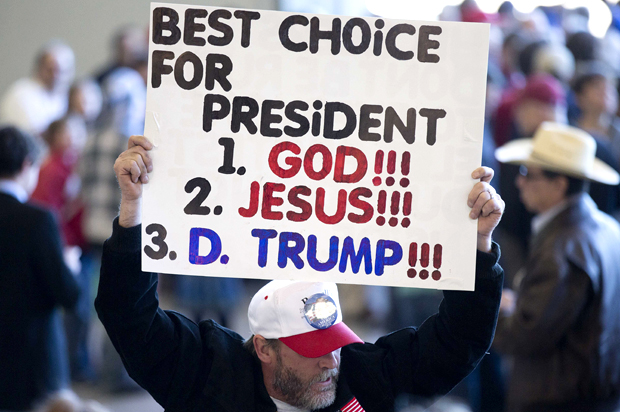

The punchline has started to land squarely on the jaw of those living in Trump country, a land that time forgot. Three excerpts follow from reports about #MAGA voters now in the crosshairs. They haven’t exactly lost their religion when it comes to their idol, but they have come to realize that being told your supreme may be attached to a steep price tag.

From Nicholas Kristoff of the New York Times:

I came to Trump country to see how voters react as Trump moves from glorious campaign promises to the messier task of governing. While conservatives often decry government spending in general, red states generally receive more in federal government benefits than blue states do — and thus are often at greater risk from someone like Trump.

Ezekiel Moreno, 35, a Navy veteran, was stocking groceries in a supermarket at night — “a dead-end job,” as he describes it — when he was accepted in WorkAdvance two years ago. That training led him to a job at M&M Manufacturing, which makes aerospace parts, and to steady pay increases.

“We’ve moved out of an apartment and into a house,” Moreno told me, explaining how his new job has changed his family’s life. “My daughter is taking violin lessons, and my other daughter has a math tutor.”

Moreno was sitting at a table with his boss, Rocky Payton, the factory’s general manager, and Amy Saum, the human resources manager. All said they had voted for Trump, and all were bewildered that he wanted to cut funds that channel people into good manufacturing jobs.

“There’s a lot of wasteful spending, so cut other places,” Moreno said.

Payton suggested that if the government wants to cut budgets, it should target “Obama phones” provided to low-income Americans. (In fact, the program predates President Barack Obama and is financed by telecom companies rather than by taxpayers.) …

Judy Banks, a 70-year-old struggling to get by, said she voted for Trump because “he was talking about getting rid of those illegals.” But Banks now finds herself shocked that he also has his sights on funds for the Labor Department’s Senior Community Service Employment Program, which is her lifeline. It pays senior citizens a minimum wage to hold public service jobs.•

From Yamiche Alcindor of the New York Times:

KINSMAN, Ohio — For years, Tammy and Joseph Pavlic tried to ignore the cracked ceiling in their living room, the growing hole next to their shower and the deteriorating roof they feared might one day give out. Mr. Pavlic worked for decades installing and repairing air-conditioning and heating units, but three years ago, with multiple sclerosis advancing, he had to leave his job.

By 2015, Ms. Pavlic was supporting her husband and their three children on an annual salary of $9,000, earned at a restaurant. That year, they tapped a county program funded by Congress, called the HOME Investment Partnerships Program, to help repair their house.

The next year, they voted for Donald J. Trump, who has moved to eliminate the HOME program.

The Pavlics’ ceiling may no longer be cracked, but in the zero-sum game that Mr. Trump’s budget seeks to set up, the nation is showing new fissures. The president’s budget proposal would cut deeply into the Department of Housing and Urban Development, paring rental assistance and eliminating heating and air-conditioning aid, energy-efficiency assistance, and partnerships with local governments like HOME. With the savings, Mr. Trump says, he would beef up military spending and build a wall along the Mexican border.

“Keeping the country safe compared to keeping my bathroom safe isn’t even a comparison,” Mr. Pavlic, 42, said. “We have people who are coming into this country who are trying to hurt us, and I think that we need to be protected.”

His wife is hoping Mr. Trump changes his mind.

“I am glad that he is our president, but I do believe, though, that if he could see this from a personal point of view that he would probably maybe change his mind about cutting this program,” Ms. Pavlic, 44, said. “Any mom wants their kids to be safe, so any mom wants their home to be safe.”•

From Sean Collins-Walsh of the Austin-America Statesman:

MAVERICK COUNTY — On a cliff overlooking the Rio Grande, Dob Cunningham got out of his four-wheeler, walked across a patch of wildflowers poking out from the rocks and stopped at a small, rough concrete block adorned with horseshoes, spurs and a Masonic emblem. Under raised letters reading “DOB,” the year 1934 was carved into the concrete, with a blank space to the right.It was Cunningham’s headstone.

“That way it’s done,” he said. “I didn’t want anyone to go and spend a bunch of money on it.”

Working as a farm hand in his youth, serving 30 years in the Border Patrol in his prime and tending to an 800-acre ranch with his wife, Kay, in his golden years, Cunningham has spent his whole life on the border, and he’s seen it change. Growing up, he would wade across the river to play baseball with kids in Mexico, and those who came north were polite. In recent years, he said, migrants have broken into his house, and drug smugglers traverse his property regularly.

Cunningham voted for Donald Trump — more importantly, he said, he voted “against Hillary” because he and Kay “didn’t want to see the country go socialism” — and agrees with the president’s desire to secure the border. But he opposes Trump’s plan to build a border wall from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico, saying it won’t work along the Rio Grande because of flooding. If the federal government tries to condemn part of his property to build the wall, Cunningham plans to fight as long as he can afford to.

“The government or the illegals won’t run me off,” he said. “We’ve lived here and we’ve raised a daughter here, and I’ve put a lot of sweat and blood in this place. We don’t want to just give it away.”•