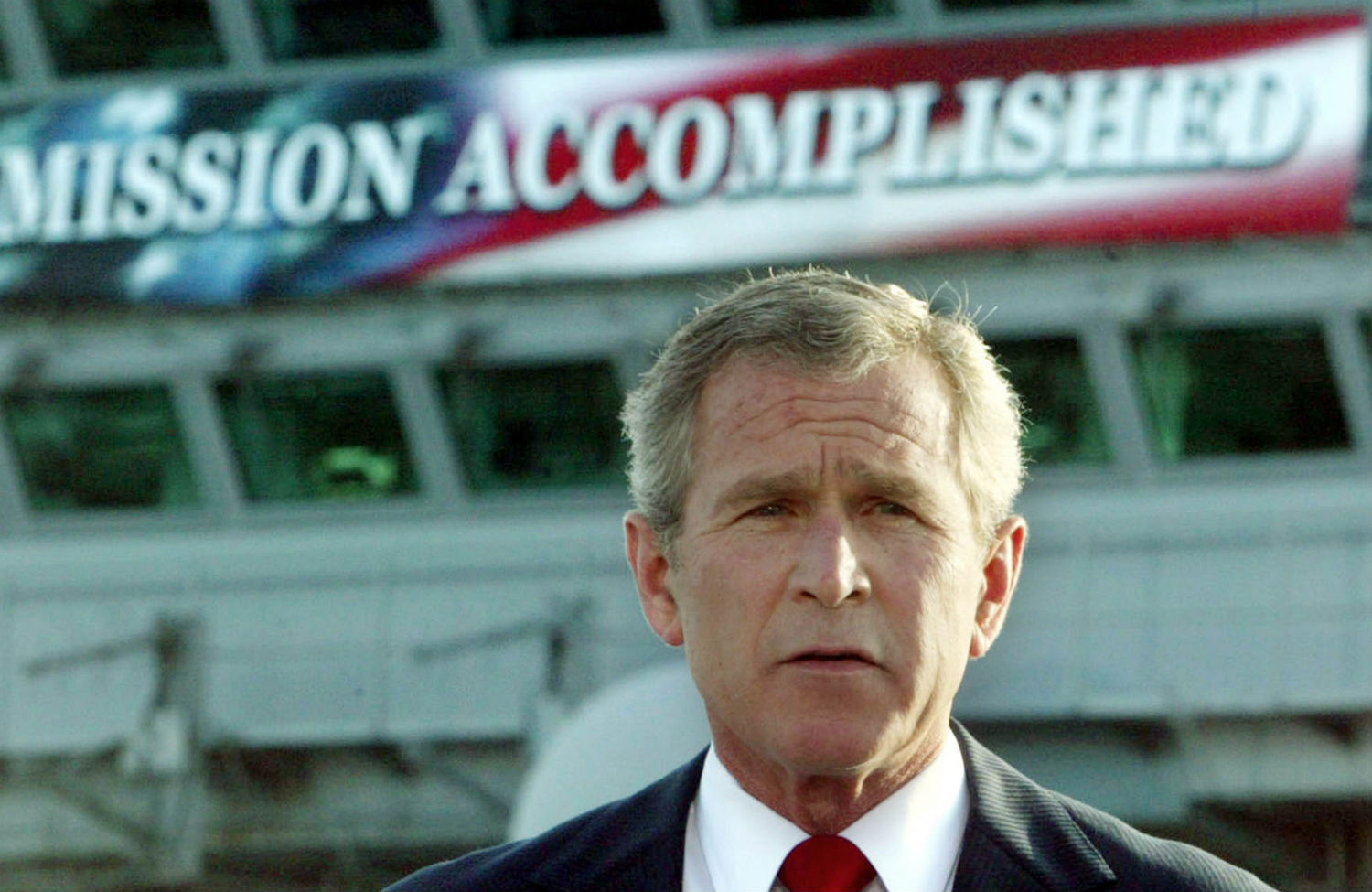

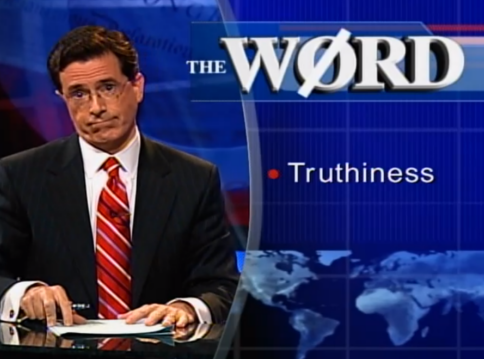

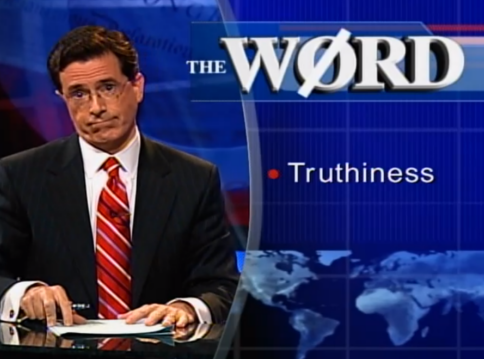

As The Colbert Report fades to black on Comedy Central, it’s a good time to recall that the year before “truthiness” laughingly made its way into the lexicon in 2005, Ron Suskind introduced the concept into the American consciousness in one of the best pieces of political journalism in memory, his jaw-dropping New York Times Magazine article, “Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush.” So inconceivable was the story’s idea that our government was being run by something other than a “reality-based community,” that those in power were operating in willful denial of facts, that many questioned Suskind’s work, but it all, sadly, turned out to be true, so true. Two excerpts follow.

______________________________

In the summer of 2002, after I had written an article in Esquire that the White House didn’t like about Bush’s former communications director, Karen Hughes, I had a meeting with a senior adviser to Bush. He expressed the White House’s displeasure, and then he told me something that at the time I didn’t fully comprehend — but which I now believe gets to the very heart of the Bush presidency.

The aide said that guys like me were ”in what we call the reality-based community,” which he defined as people who ”believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.” I nodded and murmured something about enlightenment principles and empiricism. He cut me off. ”That’s not the way the world really works anymore,” he continued. ”We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality — judiciously, as you will — we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

Who besides guys like me are part of the reality-based community? Many of the other elected officials in Washington, it would seem. A group of Democratic and Republican members of Congress were called in to discuss Iraq sometime before the October 2002 vote authorizing Bush to move forward. A Republican senator recently told Time Magazine that the president walked in and said: ”Look, I want your vote. I’m not going to debate it with you.” When one of the senators began to ask a question, Bush snapped, ”Look, I’m not going to debate it with you.”

The 9/11 commission did not directly address the question of whether Bush exerted influence over the intelligence community about the existence of weapons of mass destruction. That question will be investigated after the election, but if no tangible evidence of undue pressure is found, few officials or alumni of the administration whom I spoke to are likely to be surprised. ”If you operate in a certain way — by saying this is how I want to justify what I’ve already decided to do, and I don’t care how you pull it off — you guarantee that you’ll get faulty, one-sided information,” Paul O’Neill, who was asked to resign his post of treasury secretary in December 2002, said when we had dinner a few weeks ago. ”You don’t have to issue an edict, or twist arms, or be overt.”

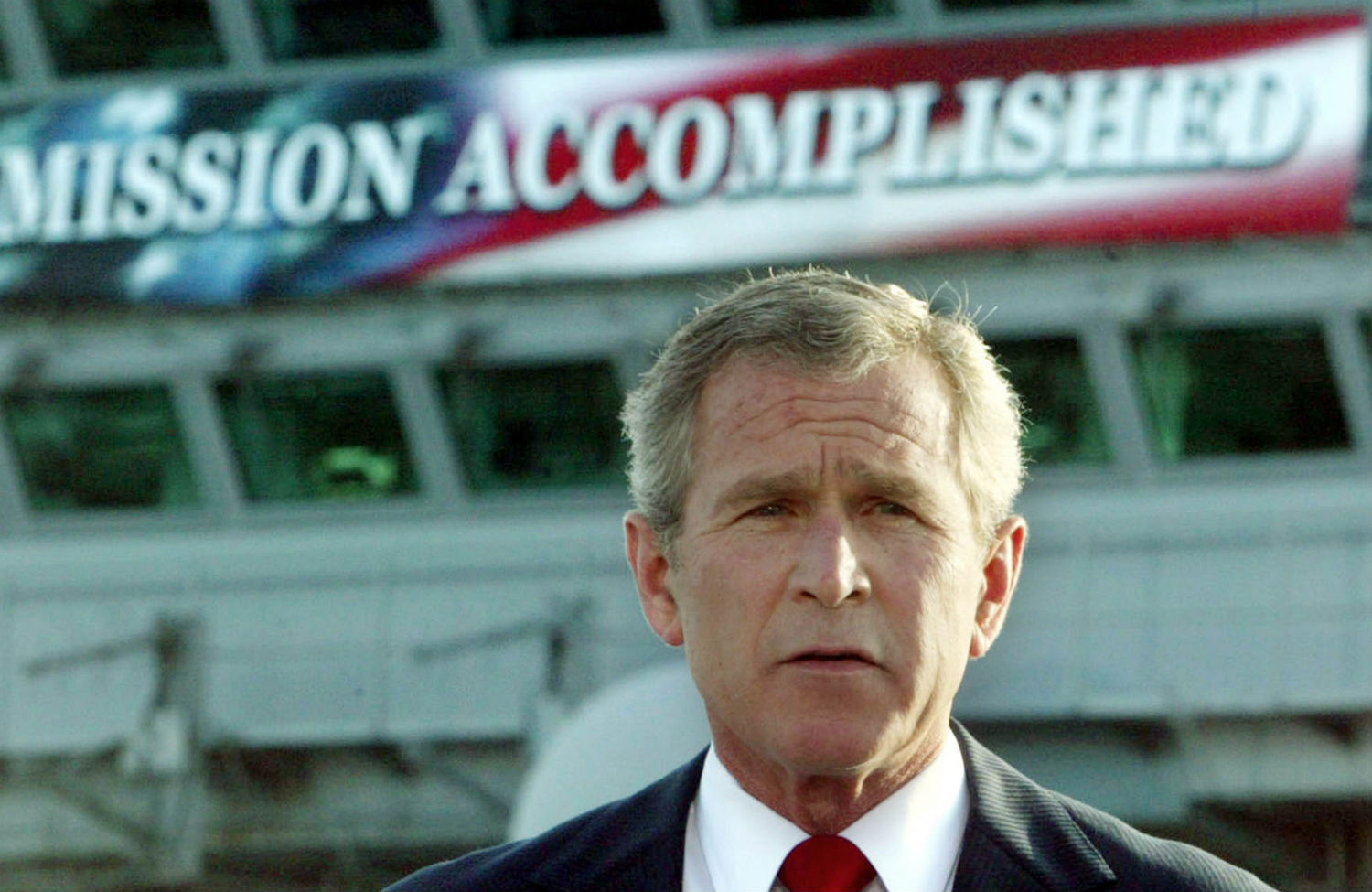

In a way, the president got what he wanted: a National Intelligence Estimate on W.M.D. that creatively marshaled a few thin facts, and then Colin Powell putting his credibility on the line at the United Nations in a show of faith. That was enough for George W. Bush to press forward and invade Iraq. As he told his quasi-memoirist, Bob Woodward, in ”Plan of Attack”: ”Going into this period, I was praying for strength to do the Lord’s will. . . . I’m surely not going to justify the war based upon God. Understand that. Nevertheless, in my case, I pray to be as good a messenger of his will as possible.”

Machiavelli’s oft-cited line about the adequacy of the perception of power prompts a question. Is the appearance of confidence as important as its possession? Can confidence — true confidence — be willed? Or must it be earned?

George W. Bush, clearly, is one of history’s great confidence men.

______________________________

There is one story about Bush’s particular brand of certainty I am able to piece together and tell for the record.

In the Oval Office in December 2002, the president met with a few ranking senators and members of the House, both Republicans and Democrats. In those days, there were high hopes that the United States-sponsored ”road map” for the Israelis and Palestinians would be a pathway to peace, and the discussion that wintry day was, in part, about countries providing peacekeeping forces in the region. The problem, everyone agreed, was that a number of European countries, like France and Germany, had armies that were not trusted by either the Israelis or Palestinians. One congressman — the Hungarian-born Tom Lantos, a Democrat from California and the only Holocaust survivor in Congress — mentioned that the Scandinavian countries were viewed more positively. Lantos went on to describe for the president how the Swedish Army might be an ideal candidate to anchor a small peacekeeping force on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Sweden has a well-trained force of about 25,000. The president looked at him appraisingly, several people in the room recall.

”I don’t know why you’re talking about Sweden,” Bush said. ”They’re the neutral one. They don’t have an army.”

Lantos paused, a little shocked, and offered a gentlemanly reply: ”Mr. President, you may have thought that I said Switzerland. They’re the ones that are historically neutral, without an army.” Then Lantos mentioned, in a gracious aside, that the Swiss do have a tough national guard to protect the country in the event of invasion.

Bush held to his view. ”No, no, it’s Sweden that has no army.”

The room went silent, until someone changed the subject.”•