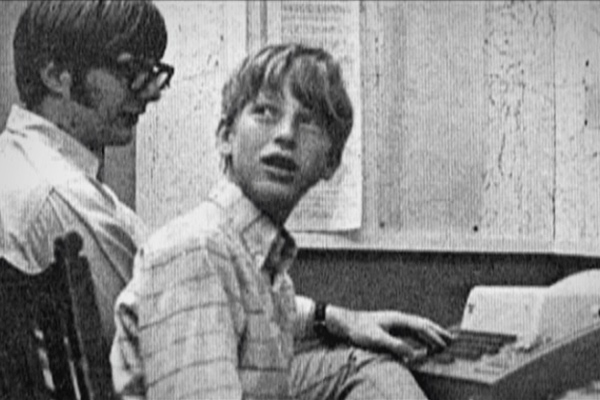

Bill Gates’ AMAs at Reddit are always fun, wide-ranging affairs. Below are some early exchanges from one he’s currently doing.

_____________________________

Question:

In your opinion, has technology made the masses less intelligent?

Bill Gates:

Technology is not making people less intelligent. If you just look at the complexity people like in Entertainment you can see a big change over my lifetime. Technology is letting people get their questions answered better so they stay more curious. It makes it easier to know a lot of topics which turns out to be pretty important to contribute to solving complex problems.

_____________________________

Question:

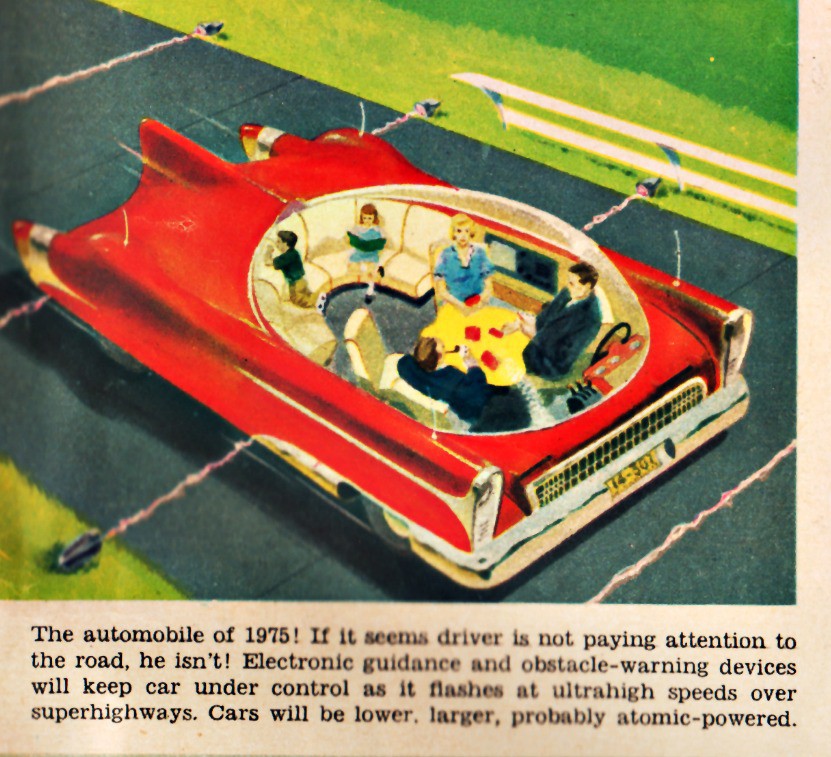

2015 will mark the 30th anniversary of Microsoft Windows. What do you think the next 30 years holds in terms of technology? What will personal computing will look like in 2045?

Bill Gates:

There will be more progress in the next 30 years than ever. Even in the next 10 problems like vision and speech understanding and translation will be very good. Mechanical robot tasks like picking fruit or moving a hospital patient will be solved. Once computers/robots get to a level of capability where seeing and moving is easy for them then they will be used very extensively.

One project I am working on with Microsoft is the Personal Agent which will remember everything and help you go back and find things and help you pick what things to pay attention to. The idea that you have to find applications and pick them and they each are trying to tell you what is new is just not the efficient model – the agent will help solve this. It will work across all your devices.

_____________________________

Question:

What do you think has improved life the most in poor countries in the last 5 years?

Bill Gates:

Vaccines make the top of the list. Being able to grow up healthy is the most basic thing. So many kids get infectious diseases and don’t develop mentally and physically. I was in Berlin yesterday helping raise $7.5B for vaccines for kids in poor countries. We barely made it but we did which is so exciting to me!

_____________________________

Question:

What is your opinion on bitcoins or cyptocurency as a whole? Also do you own any yourself?

Bill Gates:

Bitcoin is an exciting new technology. For our Foundation work we are doing digital currency to help the poor get banking services. We don’t use bitcoin specifically for two reasons. One is that the poor shouldn’t have a currency whose value goes up and down a lot compared to their local currency. Second is that if a mistake is made in who you pay then you need to be able to reverse it so anonymity wouldn’t work.

Overall financial transactions will get cheaper using the work we do and Bitcoin related approaches.

Making sure that it doesn’t help terrorists is a challenge for all new technology.

_____________________________

Question:

Is there anything in life that you regret doing or not doing?

Bill Gates:

I feel pretty stupid that I don’t know any foreign languages. I took Latin and Greek in High School and got A’s and I guess it helps my vocabulary but I wish I knew French or Arabic or Chinese. I keep hoping to get time to study one of these – probably French because it is the easiest. I did Duolingo for awhile but didn’t keep it up. Mark Zuckerberg amazingly learned Mandarin and did a Q&A with Chinese students – incredible.

_____________________________

Question:

What do you think about life-extending and immortality research?

Bill Gates:

It seems pretty egocentric while we still have malaria and TB for rich people to fund things so they can live longer. It would be nice to live longer though I admit.•