Over the weekend, the President of the United States held a Pennsylvania rally that played out like a Maoist “Speak Bitterness” meeting, threatened First Amendment rights and invited murderous Filipino strongman Rodrigo Duterte to the White House. All of that was appalling, though it can’t be considered shocking at this point.

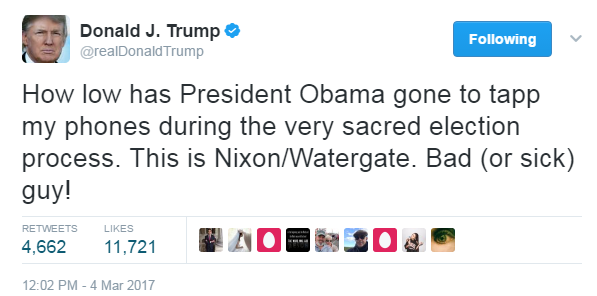

This morning, I read Peter Baker’s NYT take on Trump’s first 100 days, which was way too hopeful based on anything remotely connected to reality, and then, this afternoon, I came across this tweet:

.@MichaelKinsley has written #SomethingNiceAboutTrump and would like suggestions for more https://t.co/GAVJzTaYES

— NYT Opinion (@nytopinion) April 30, 2017

Has everyone lost their damn mind?

Trump is incompetent, a sociopath and a kleptocrat, that’s clear, but what’s still TBD is the extent of Russian interference in our election and who was complicit. The lack of Congressional interest in this potential scandal could be partisanship or it may be something more sinister. Not to go all Louise Mensch, but there seems to be an endless stream of smoke. Let’s hope James Comey and the IC community are true or we may never know the answers.

Despite all those questions, one thing, however, is certain: We have a dreadful, deeply un-American person in the highest office in the land, and nearly 63 million citizens approve.

· · ·

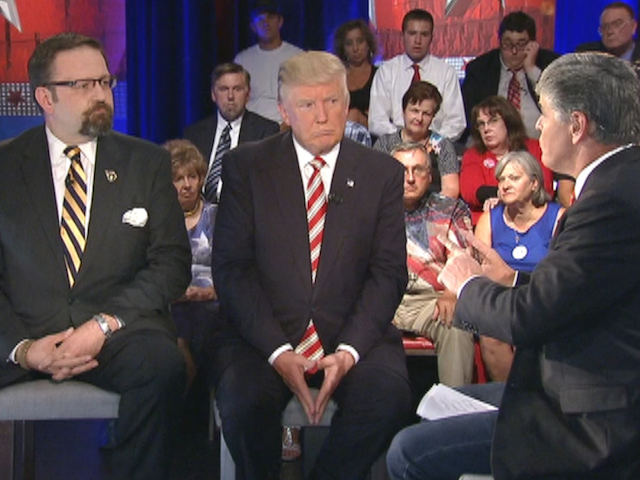

Rosalind S. Helderman and Tom Hamburger’s WaPo piece about the hard right going soft on the Kremlin wonders about the reasons for Putin and his cohort’s return of admiration, which likely stems from something other than mere camaraderie. As retired CIA Russian expert Steven L. Hall tells them, “My assessment is that it’s definitely part of something bigger.”

An excerpt:

On issues including gun rights, terrorism and same-sex marriage, many leading advocates on the right who grew frustrated with their country’s leftward tilt under President Barack Obama have forged ties with well-connected Russians and come to see that country’s authoritarian leader, Vladimir Putin, as a potential ally.

The attitude adjustment among many conservative activists helps explain one of most curious aspects of the 2016 presidential race: a softening among many conservatives of their historically hard-line views of Russia. To the alarm of some in the GOP’s national security establishment, support in the party base for then-candidate Donald Trump did not wane even after he rejected the tough tone of 2012 nominee Mitt Romney, who called Russia America’s No. 1 foe, and repeatedly praised Putin.

The burgeoning alliance between Russians and U.S. conservatives was apparent in several events in late 2015, as the Republican nomination battle intensified.

Top officials from the National Rifle Association, whose annual meeting Friday featured an address by Trump for the third time in three years, traveled to Moscow to visit a Russian gun manufacturer and meet government officials.

About the same time in December 2015, evangelist Franklin Graham met privately with Putin for 45 minutes, securing from the Russian president an offer to help with an upcoming conference on the persecution of Christians. Graham was impressed, telling The Washington Post that Putin “answers questions very directly and doesn’t dodge them like a lot of our politicians do.”•