The simple fact of the matter is beyond telling. In the 18 years since it happened, I have often tried to put it into words. Now, once and for all, I should like to employ every resource of language I know in giving an account of at least the outward and inward circumstances. This ‘fact’ consists in a certainty I acquired by accident at the age of sixteen or seventeen; ever since then, the memory of it has directed the best part of me toward seeking a means of finding it again, and for good.

My memories of child-hood and adolescence are deeply marked by a series of attempts to experience the beyond, and those random attempts brought me to the ultimate experiment, the fundamental experience of which I speak.

At about the age of six, having been taught no kind of religious belief whatsoever, I struck up against the stark problem of death.

I passed some atrocious nights, feeling my stomach clawed to shreds and my breathing half throttled by the anguish of nothingness, the ‘no more of anything’.

One night when I was about eleven, relaxing my entire body, I calmed the terror and revulsion of my organism before the unknown, and a new feeling came alive in me; hope, and a foretaste of the imperishable. But I wanted more, I wanted a certainty. At fifteen or sixteen I began my experiments, a search without direction or system.

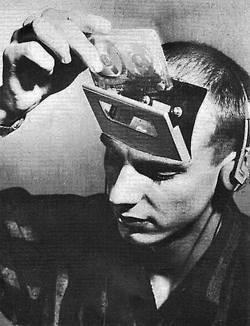

Finding no way to experiment directly on death-on my death-I tried to study my sleep, assuming an analogy between the two.

By various devices I attempted to enter sleep in a waking state. The undertaking is not so utterly absurd as it sounds, but in certain respects it is perilous. I could not go very far with it; my own organism gave me some serious warnings of the risks I was running. One day, however, I decided to tackle the problem of death itself.

I would put my body into a state approaching as close as possible that of physiological death, and still concentrate all my attention on remaining conscious and registering everything that might take place.

I had in my possession some carbon tetrachloride, which I used to kill beetles for my collection. Knowing this substance belongs to the same chemical family as chloroform (it is even more toxic), I thought I could regulate its action very simply and easily: the moment I began to lose consciousness, my hand would fall from my nostrils carrying with it the handkerchief moistened with the volatile fluid. Later on I repeated the experiment –in the presence of friends, who could have given me help had I needed it.

The result was always exactly the same; that is, it exceeded and even overwhelmed my expectations by bursting the limits of the possible and by projecting me brutally into another world.

First came the ordinary phenomena of asphyxiation: arterial palpitation, buzzings, sounds of heavy pumping in the temples, painful repercussions from the tiniest exterior noises, flickering lights. Then, the distinct feeling: ‘This is getting serious. The game is up,’ followed by a swift recapitulation of my life up to that moment. If I felt any slight anxiety, it remained indistinguishable from a bodily discomfort that did not affect my mind.

And my mind kept repeating to itself : ‘Careful, don’t doze off. This is just the time to keep your eyes open.’

The luminous spots that danced in front of my eyes soon filled the whole of space, which echoed with the beat of my blood- sound and light overflowing space and fusing in a single rhythm. By this time I was no longer capable of speech, even of interior speech; my mind travelled too rapidly to carry any words along with it.

I realized, in a sudden illumination, that I still had control of the hand which held the handkerchief, that I still accurately perceived the position of my body, and that I could hear and understand words uttered nearby–but that objects, words, and meanings of words had lost any significance whatsoever. It was a little like having repeated a word over and over until it shrivels and dies in your mouth: you still know what the word ‘table’ means, for instance, you could use it correctly, but it no longer truly evokes its object.

In the same way everything that made up ‘the world’ for me in my ordinary state was still there, but I felt as if it had been drained of its substance. It was nothing more than a phantasmagoria-empty, absurd, clearly outlined, and necessary all at once.

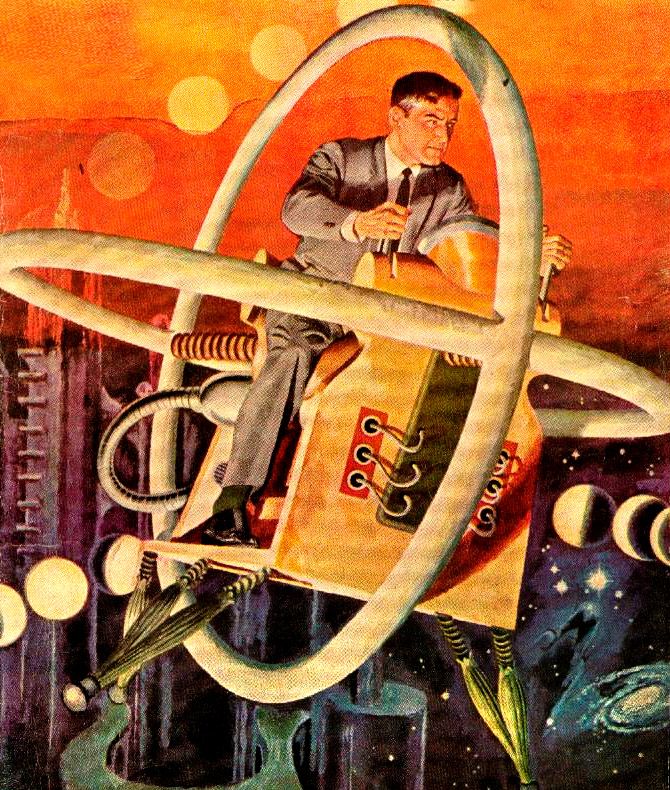

This ‘world’ lost all reality because I had abruptly entered another world, infinitely more real, an instantaneous and intense world of eternity, a concentrated flame of reality and evidence into which I had cast myself like a butterfly drawn to a lighted candle.

Then, at that moment, comes the certainty; speech must now be content to wheel in circles around the bare fact.

Certainty of what?

Words are heavy and slow, words are too shapeless or too rigid. With these wretched words I can put together only approximate statements, whereas my certainty is for me the archetype of precision. In my ordinary state of mind, all that remains thinkable and formulable of this experiment reduces to one affirmation on which I would stake my life: I feel the certainty of the existence of something else, a beyond, another world, or another form of knowledge.

In the moment just described, I knew directly, I experienced that beyond in its very reality.

It is important to repeat that in that new state I perceived and perfectly comprehended the ordinary state of being, the latter being contained within the former, as waking consciousness contains our unconscious dreams, and not the reverse. This last irreversible relation proves the superiority (in the scale of reality or consciousness) of the first state over the second.

I told myself clearly: in a little while I shall return to the so-called ‘normal state’, and perhaps the memory of this fearful revelation will cloud over; but it is in this moment that I see the truth.

All this came to me without words; meanwhile I was pierced by an even more commanding thought. With a swiftness approaching the instantaneous, it thought itself so to speak in my very substance: for all eternity I was trapped, hurled faster and faster toward ever imminent annihilation through the terrible mechanism of the Law that rejected me.

‘That’s what it is. So that’s what it is.’

My mind found no other reaction. Under the threat of something worse, I had to follow the movement.

It took a tremendous effort, which became more and more difficult, but I was obliged to make that effort, until the moment when, letting go, I doubtless fell into a brief spell of unconsciousness. My hand dropped the handkerchief, I breathed air’, and for the rest of the day I remained dazed and stupefied-with a violent headache.•