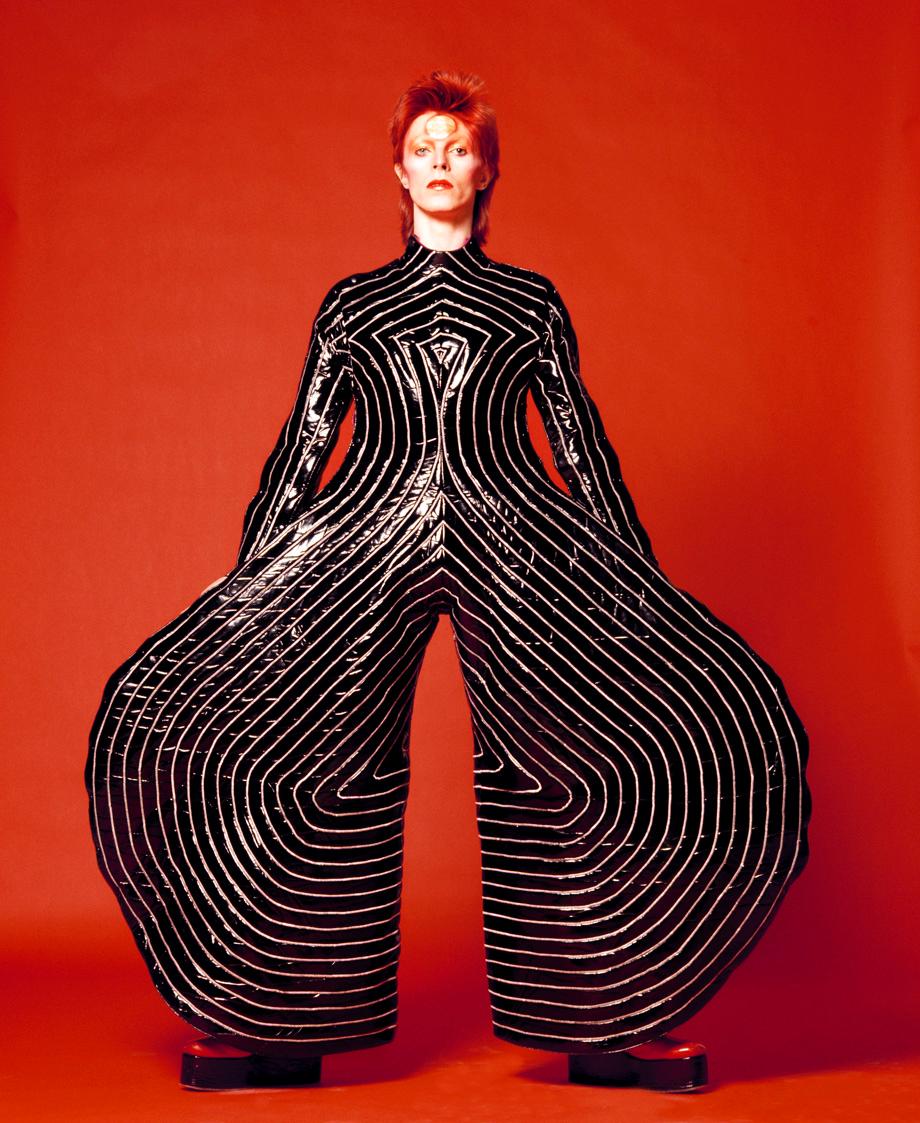

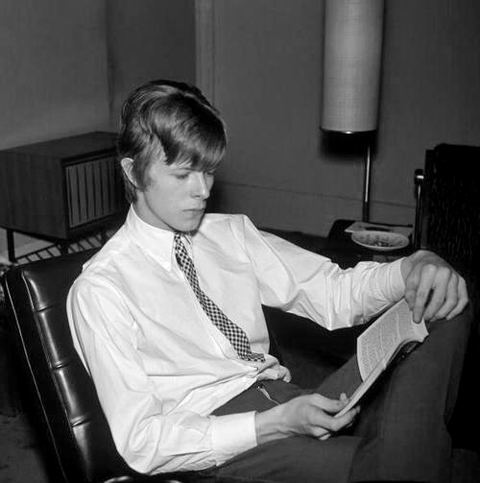

Via Liz Bury at the Guardian, here’s David Bowie’s list of must-read books that’s been released as part of an exhibition about the pop star at the Art Gallery of Ontario:

- The Age of American Unreason, Susan Jacoby (2008)

- The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, Junot Diaz (2007)

- The Coast of Utopia (trilogy), Tom Stoppard (2007)

- Teenage: The Creation of Youth 1875-1945, Jon Savage (2007)

- Fingersmith, Sarah Waters (2002)

- The Trial of Henry Kissinger, Christopher Hitchens (2001)

- Mr Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder, Lawrence Weschler (1997)

- A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1890-1924, Orlando Figes (1997)

- The Insult, Rupert Thomson (1996)

- Wonder Boys, Michael Chabon (1995)

- The Bird Artist, Howard Norman (1994)

- Kafka Was the Rage: A Greenwich Village Memoir, Anatole Broyard (1993)

- Beyond the Brillo Box: The Visual Arts in Post-Historical Perspective, Arthur C. Danto (1992)

- Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson, Camille Paglia (1990)

- David Bomberg, Richard Cork (1988)

- Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm and Blues and the Southern Dream of Freedom, Peter Guralnick (1986)

- The Songlines, Bruce Chatwin (1986)

- Hawksmoor, Peter Ackroyd (1985)

- Nowhere to Run: The Story of Soul Music, Gerri Hirshey (1984)

- Nights at the Circus, Angela Carter (1984)

- Money, Martin Amis (1984)

- White Noise, Don DeLillo (1984)

- Flaubert’s Parrot, Julian Barnes (1984)

- The Life and Times of Little Richard, Charles White (1984)

- A People’s History of the United States, Howard Zinn (1980)

- A Confederacy of Dunces, John Kennedy Toole (1980)

- Interviews with Francis Bacon, David Sylvester (1980)

- Darkness at Noon, Arthur Koestler (1980)

- Earthly Powers, Anthony Burgess (1980)

- Raw, a “graphix magazine” (1980-91)

- Viz, magazine (1979 –)

- The Gnostic Gospels, Elaine Pagels (1979)

- Metropolitan Life, Fran Lebowitz (1978)

- In Between the Sheets, Ian McEwan (1978)

- Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interviews, ed Malcolm Cowley (1977)

- The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, Julian Jaynes (1976)

- Tales of Beatnik Glory, Ed Saunders (1975)

- Mystery Train, Greil Marcus (1975)

- Selected Poems, Frank O’Hara (1974)

- Before the Deluge: A Portrait of Berlin in the 1920s, Otto Friedrich (1972)

- In Bluebeard’s Castle: Some Notes Towards the Re-definition of Culture, George Steiner (1971)

- Octobriana and the Russian Underground, Peter Sadecky (1971)

- The Sound of the City: The Rise of Rock and Roll, Charlie Gillett (1970)

- The Quest for Christa T, Christa Wolf (1968)

- Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom: The Golden Age of Rock, Nik Cohn (1968)

- The Master and Margarita, Mikhail Bulgakov (1967)

- Journey into the Whirlwind, Eugenia Ginzburg (1967)

- Last Exit to Brooklyn, Hubert Selby Jr (1966)

- In Cold Blood, Truman Capote (1965)

- City of Night, John Rechy (1965)

- Herzog, Saul Bellow (1964)

- Puckoon, Spike Milligan (1963)

- The American Way of Death, Jessica Mitford (1963)

- The Sailor Who Fell from Grace With the Sea, Yukio Mishima (1963)

- The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin (1963)

- A Clockwork Orange, Anthony Burgess (1962)

- Inside the Whale and Other Essays, George Orwell (1962)

- The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Muriel Spark (1961)

- Private Eye, magazine (1961 –)

- On Having No Head: Zen and the Rediscovery of the Obvious, Douglas Harding (1961)

- Silence: Lectures and Writing, John Cage (1961)

- Strange People, Frank Edwards (1961)

- The Divided Self, RD Laing (1960)

- All the Emperor’s Horses, David Kidd (1960)

- Billy Liar, Keith Waterhouse (1959)

- The Leopard, Giuseppe di Lampedusa (1958)

- On the Road, Jack Kerouac (1957)

- The Hidden Persuaders, Vance Packard (1957)

- Room at the Top, John Braine (1957)

- A Grave for a Dolphin, Alberto Denti di Pirajno (1956)

- The Outsider, Colin Wilson (1956)

- Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov (1955)

- Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell (1949)

- The Street, Ann Petry (1946)

- Black Boy, Richard Wright (1945)